Most discussions of auto-deleveraging (ADL) (post 1, post 2 and the related threads x.com 1, x.com 2, x.com 3) start at the wrong place.

They start with who got hurt, how much, and whether the rule felt fair. By the time those questions are asked, the interesting part of the problem is already over. The system has failed in a very specific way, and ADL is no longer a choice, it is damage control.

So if we want to design better ADL mechanisms, we have to rewind the story to the moment before moral intuition kicks in. We have to understand what ADL is in the same way an engineer understands what a circuit breaker is, not as a punishment, but as a response to physics.

For the latest corrected ADL analysis, please refer to the updates in the OSS ADL GitHub repository.

1. The clean world, and the moment it breaks

In the clean world, liquidation is boring.

A trader loses money. Their margin drops. The liquidation engine closes their position at roughly the mark price. The proceeds cover the loss. The account disappears. The rest of the market continues as if nothing happened.

In that world, there is no ADL. There is no deficit. There is nothing to argue about.

ADL only exists because the clean world is not stable under stress.

When volatility spikes, when order books thin, when many accounts rush toward liquidation simultaneously, the liquidation engine stops behaving like a conveyor belt and starts behaving like a fire exit. Execution slips. Positions are closed at prices worse than expected. Suddenly, after the liquidations are “done,” the system is missing money.

That missing money is not hypothetical. It is a realized accounting shortfall. If the exchange ignores it, it is insolvent.

ADL is what happens after this failure, not before.

2. The only object ADL must produce

Strip away the implementation details and product language, and every ADL event reduces to the same mathematical object.

There exists a realized deficit. Call it $D \ge 0$.

This deficit is not a forecast. It is not a stress estimate. It is the amount by which the system’s liabilities exceed its assets after liquidation has executed under stress. Your methodology is careful to compute this deficit at the level of global stress waves, not per-market anecdotes, precisely because liquidation failures are systemic phenomena .

Now the exchange faces a hard requirement: if it wants to restore solvency immediately, it must raise a budget $B$. In the idealized model, $B = D$. In production, $B$ is often slightly larger because the mechanism does not move dollars directly, it closes contracts, in discrete units, under time pressure.

Next, the exchange chooses a set of accounts that are eligible to contribute. These are often called “winners,” but that language is misleading. They are simply the accounts the platform has decided can pay.

Call this set $W$.

For each account $i \in W$, there is a maximum amount the system can extract in this wave. Call it $c_i \ge 0$. This cap is where product promises become engineering: if you claim “profits-only,” then $c_i$ is limited to withdrawable PnL; if you allow haircuts above a buffer, $c_i$ includes that buffer; if you impose per-wave or per-account limits, those limits sit inside $c_i$.

An ADL mechanism must output a set of transfers ${h_i}$ satisfying two constraints simultaneously:

\[0 \le h_i \le c_i \quad \text{for all } i \in W, \qquad \sum_{i \in W} h_i \ge B.\]That’s it. That is the entire mathematical definition of ADL.

Everything else, queues, scores, fairness narratives, pro-rata rules, is a way of choosing which feasible vector ${h_i}$ to produce.

And from this definition, one fact drops out immediately, without philosophy or debate:

If $\sum_{i \in W} c_i < B$, then the mechanism is infeasible.

No amount of clever ranking can make money appear. If the available junior capacity cannot cover the deficit, the system must either touch a more senior layer (e.g. principal), invoke an external backstop, or accept residual insolvency.

This inequality is the first place imagination meets rigor. It tells you which arguments are real, and which are theater.

3. Why most ADL debates are confused

At this point, many discussions go off the rails because they mix two different spaces.

Exchanges do not usually execute ADL by deducting dollar balances. They execute ADL by closing positions.

That means the mechanism operates in contract space, while the outcome is judged in wealth space.

In contract space actions are discrete, positions are indivisible, and execution happens at moving prices.

In wealth space outcomes are continuous, losses are measured in dollars, and accounting invariants live.

If you conflate the two, you get numbers that look shocking but explain nothing.

Tarun’s corrected analysis makes this distinction explicit. A “queue overshoot” measured in wealth space can be very large because it is a stylized abstraction of how concentrated a priority rule is. Meanwhile, the actual PnL transferred from winners under the executed ADL path can be an order of magnitude smaller, because winners are often heavily overcollateralized and because execution granularity matters .

This is not a bug. It is physics.

That is why his methodology insists on evaluating production impact via a two-pass counterfactual: replay the same realized price path with and without ADL state updates, then measure the difference. Only then are you measuring what ADL actually did, not what a narrative says it did.

Once you internalize this separation, a lot of online arguments simply dissolve. People are often arguing about different objects without realizing it.

At this point, a natural objection appears:

“Isn’t this just unrealized PnL? If you wait long enough, doesn’t the overshoot disappear?”

The answer is yes - and that answer is precisely the problem.

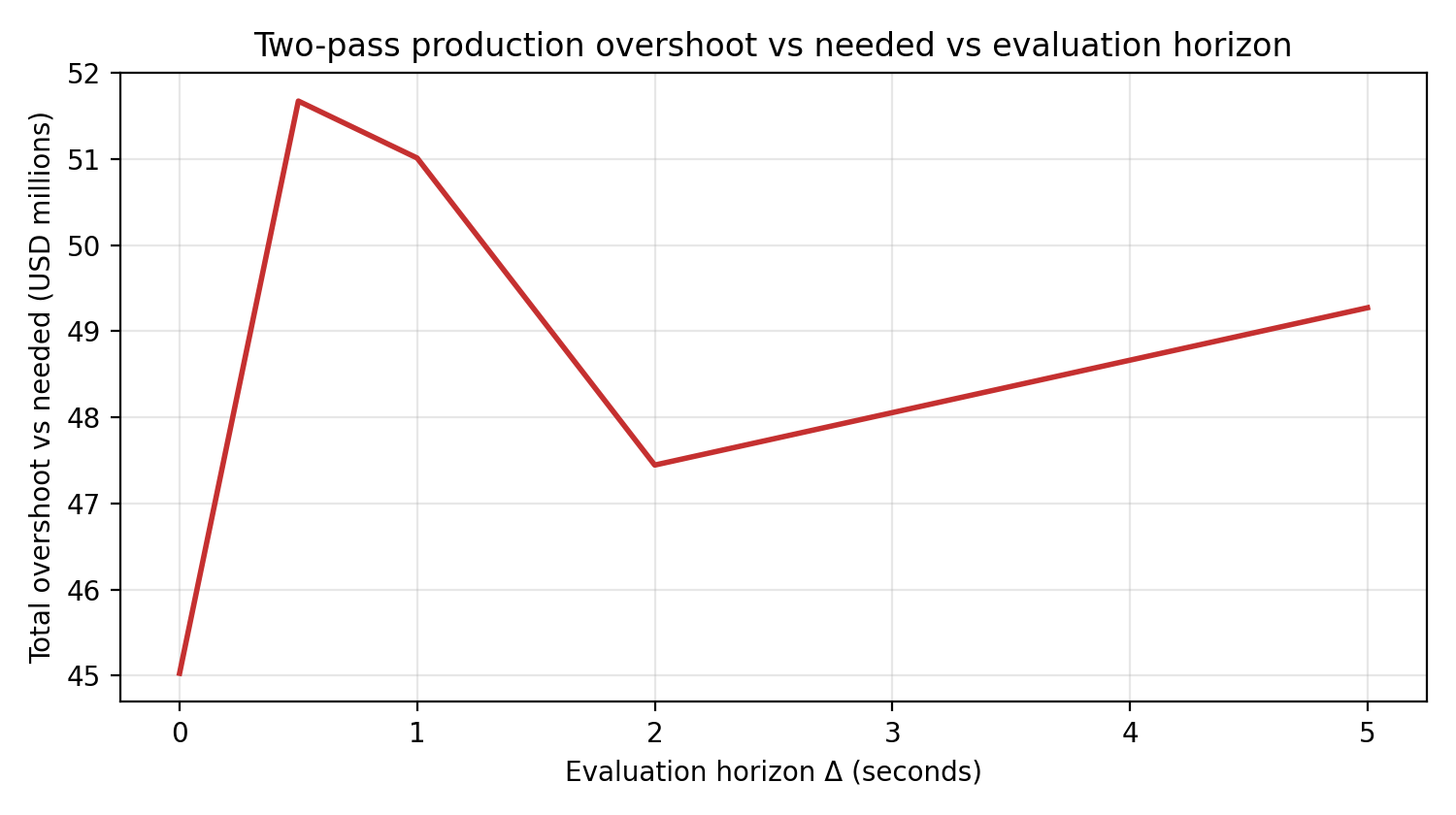

Figure - Overshoot vs evaluation horizon

This figure shows measured production overshoot (the Oct 10 Hyperliquid event) as a function of the evaluation horizon $\Delta$: how long the system is allowed to unwind positions, realize PnL, and release queued equity. At short horizons, overshoot appears severe. As the horizon lengthens, some equity converts into realized gains and the measured overshoot declines.

But this does not make overshoot illusory. It reveals that overshoot is not an invariant of the system - it is a function of how patient the system is allowed to be.

Changing $\Delta$ quietly assumes continued liquidity, orderly unwinds, and users willing to tolerate frozen capital. Those are economic assumptions, not accounting identities. Time does not eliminate pain; it reallocates who bears it.

4. What ADL is really optimizing

Now we can finally talk about goals.

ADL is not optimizing “fairness” in the moral sense. It is optimizing under three competing constraints:

- Solvency, the deficit must be covered quickly and reliably.

- Bounded moral hazard, losses must not concentrate so predictably that they create exploitable incentives.

- Revenue / LTV preservation, the mechanism must not destroy the participant base that generates future fees.

The ADL trilemma result in the ADL paper formalizes what practitioners already feel: for static policy families, you cannot satisfy all three simultaneously. If the system lives in a structural deficit regime, losses must land somewhere. Changing the allocation rule changes who bears them and how they show up in behavior.

This is not pessimism. It is accounting.

So the real question is not:

Can we design an ADL mechanism that is fair, solvent, and revenue-maximizing?

It is:

Given the physics of liquidation failure and execution constraints, how do we shape loss allocation so that solvency is restored with the least collateral damage?

That is a design problem worthy of imagination.

5. Why queues exist, and what objective they secretly optimize

Let’s do a small act of imagination before we write a single equation.

Picture the exchange during a violent move (e.g. the Oct 10 Hyperliquid event). Liquidations are firing. Order books are thin. The system has already failed once, that’s why ADL is running at all. At this point, the operator has a single overriding instinct:

Fix this now. Touch as few things as possible. Do not let the failure propagate.

That instinct is not irrational. It is operational.

Under extreme latency and execution pressure, every additional account you touch adds state transitions, increases the chance of secondary failures, and widens the surface area for disputes and confusion.

So the implicit objective becomes:

Restore solvency while minimizing how many accounts are affected.

Now let’s translate that instinct into math.

Suppose we are solving the ADL allocation problem: \(0 \le h_i \le c_i,\qquad \sum_i h_i \ge B.\)

Add the hidden objective: \(\min \#{i : h_i > 0}.\)

This is not an exotic objective. It is exactly the desire to “touch as few accounts as possible.” In mathematical terms, you are minimizing a sparsity measure, the number of nonzero entries in the haircut vector.

What kind of solution does this produce?

A greedy one.

You take the largest available capacity first. If that’s not enough, you take the next largest. You keep going until the budget is met.

That is a queue.

This is the first important reframing:

Queues are not arbitrary. They are the natural solution to a sparsity objective.

Once you see this, several things become clear all at once.

First, concentration is not a bug. It is the intended outcome of the objective. If you minimize the number of affected accounts, you necessarily concentrate pain on a few.

Second, changing the score, entry PnL, leverage, buffer, time-in-position, does not change the geometry. It only changes who ends up at the front of the line. The mechanism is still optimizing sparsity.

This is why queue debates feel endless. People argue about whether the ranking is “fair,” but the underlying objective is never questioned.

At this point, we can keep adding definitions, but the problem we’re studying is simpler than the vocabulary makes it sound.

Under stress, ADL is a triage procedure: the system must shed risk fast, with incomplete information, and under hard operational deadlines. When you do triage with a queue, you are not just choosing how much to take, you are choosing who gets touched first. That is where perception becomes brittle.

A physical analogy makes this brittleness easier to see without losing rigor. Think of the system as a ship in a storm: the captain must throw cargo overboard to keep the ship afloat. The ship does not care about fairness. It cares about staying upright.

With that in mind, consider the queue again, but in the language of load and balance.

6. The brittleness of queues (and why it shows up as outrage)

Now imagine standing on the deck of the ship again.

If the captain throws one container overboard, the ship stabilizes. If the captain throws two, it stabilizes faster. But if the captain throws the wrong one, the one holding critical supplies, the voyage becomes pointless.

This is exactly how queues fail in perception.

Mathematically, queue allocations are discontinuous. A small change in state can cause a large jump in outcome. Two accounts can be nearly identical in risk and exposure, but one gets wiped and the other gets nothing because of a tiny ranking difference.

From a control perspective, queues are brittle. From a human perspective, they feel arbitrary.

This is not about sentiment. It is about sensitivity.

A mechanism whose output changes sharply under small perturbations is hard to reason about, hard to hedge against, and easy to feel targeted by.

That brittleness is what shows up later as “fairness outrage,” even if the rule was announced in advance.

And then comes the deeper problem.

7. When queues become gameable

Up to now, we’ve assumed the ranking score reflects something real, some notion of risk or seniority.

But ask yourself a sharper question:

Can a trader change their expected ADL exposure without changing the system’s tail risk?

If the answer is yes, the mechanism will be attacked.

Before designing around this fear, we should ask what actually happens during ADL events.

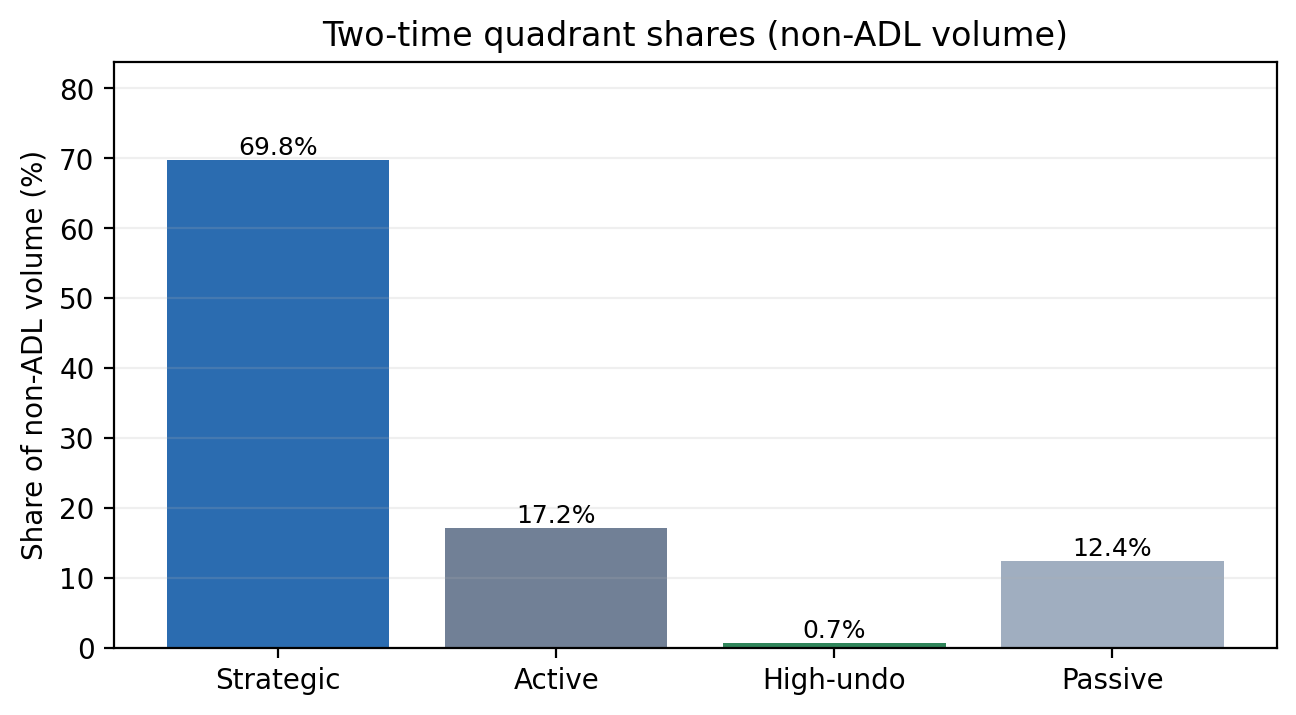

Figure - Behavioral regimes during ADL

This figure shows how trading volume during ADL events is distributed across behavioral regimes. Most volume falls into passive or low-activity categories. Highly strategic “undo-heavy” behavior exists, but it represents a small fraction of total volume.

The important takeaway is not that gaming does not exist - it does - but that gaming does not dominate system mass. Any ADL mechanism that assumes most participants are actively optimizing against it is designing for an edge case.

Entry-price PnL is the canonical example.

It is tempting because it looks like “winnings.” But it is path-dependent and resettable. A trader can close and reopen, split exposure across accounts, or reshuffle risk across correlated markets

and materially change their queue rank while leaving the exchange’s insolvency risk unchanged.

At that point, the queue is no longer allocating based on externality. It is allocating based on path artifacts.

From a rational point of view, this is the wrong variable.

This leads to an even sharper misconception: that the traders who undo the most are the ones causing the most damage.

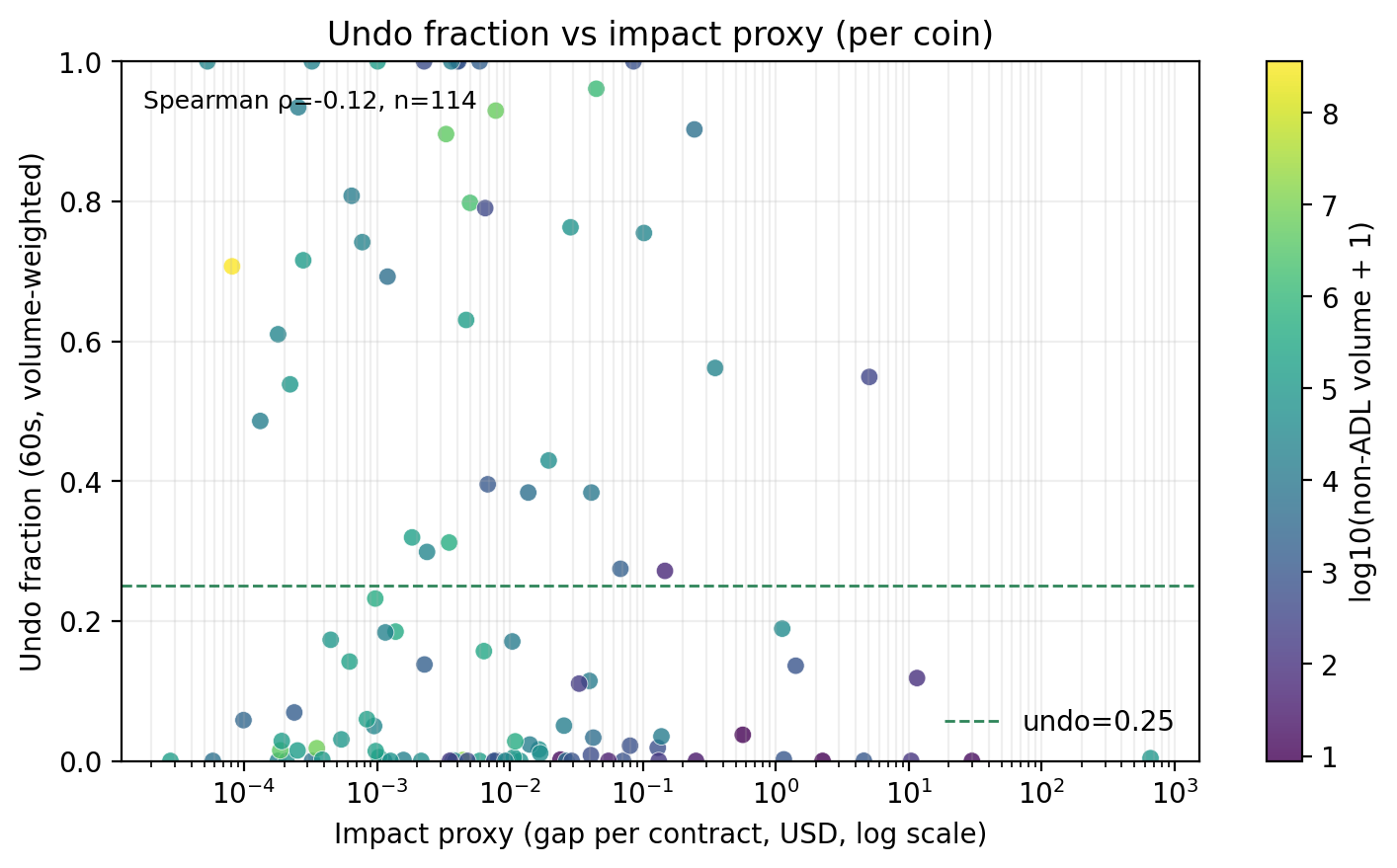

Figure - Undo behavior vs realized system impact

This figure shows little correlation between undo intensity and realized contribution to system-level shortfall. Some of the largest sources of insolvency pressure are slow-moving, highly capitalized positions that exhibit minimal undo behavior.

This breaks a tempting but incorrect design instinct: “just punish the flippers.”

Undo is a response to stress, not a measure of externality.

If your equation depends on something a participant can erase without changing the physics of the system, you are measuring the wrong thing.

8. The imagination shift: from “who pays first” to “what shape of pain survives”

Instead of asking:

“Who should we hit first?”

Ask:

“What distribution of pain keeps the system stable and predictable under stress?”

Picture the deficit not as a list to be consumed, but as a force applied to a structure.

If you apply the force at a single point, the structure snaps. If you spread it evenly everywhere, the structure sags and loses control. Between these extremes lies a family of shapes, and that is the ADL design space.

Once you think this way, queues are no longer the default. They are one extreme.

9. Why pro-rata appears when you penalize spikes

Now we let the math back in, gently.

Suppose instead of minimizing “how many accounts are touched,” you want to avoid extreme concentration. A clean way to encode that is to penalize large haircut fractions.

Define a “pain” function $\phi(x)$ that grows faster than linearly. For example, $x^2$ or any convex function. Now consider:

\[\min_h \sum_i \phi\left(\frac{h_i}{c_i}\right) \quad \text{subject to} \quad 0 \le h_i \le c_i, \sum_i h_i = B.\]Convexity is the mathematical expression of the intuition:

“Twice the haircut hurts more than twice as much.”

When you solve problems like this, something remarkable happens: the optimizer tries to equalize marginal pain. The result is not a spike. It is a spread.

This is where pro-rata comes from, not from ideology, but from geometry.

And the ADL paper goes further: once you impose basic invariances, that splitting accounts doesn’t help, that rescaling doesn’t change the structure, that more capacity doesn’t perversely reduce burden, pro-rata is not just a solution. It is essentially the only one.

That’s a deeply insightful result. Once the picture is right, the math has nowhere else to go.

10. Why naïve pro-rata still isn’t enough

But our imagination also tells us where pro-rata fails.

Return to the ship.

If some stacks are unstable, likely to topple and cause future damage, you do not remove equal weight from every stack. You remove more from the dangerous ones.

This is where risk-weighted pro-rata enters naturally.

Instead of distributing pain over “wealth” alone, you distribute it over externality, over contribution to tail risk.

Mathematically, this just means introducing weights $w_i$ that reflect risk: \(h_i \propto w_i \cdot c_i,\) with normalization and caps.

The brilliance here is not the formula. It is the shift in what the mechanism pays attention to.

Not history. Not entry points. Not narratives.

But what breaks the system if repeated.

11. A warning before we continue

At this point, it is tempting to believe we have escaped the trilemma.

We have not.

What we have done is move along the feasible frontier, trading some operational simplicity for smoother behavior, trading some immediacy for predictability.

The physics still applies. Some concentration is unavoidable. Some incentives will always exist. Execution will always impose granularity.

But now we are designing with eyes open.

12. Seniority is not a slogan

At some point in almost every ADL debate, someone says a version of the same sentence:

“We only haircut profits, not principal.”

It sounds reassuring. It sounds fair. It sounds like a moral rule.

But as a mechanism designer, you are not allowed to stop at slogans. You have to ask a harder question:

What state variable does the mechanism actually observe?

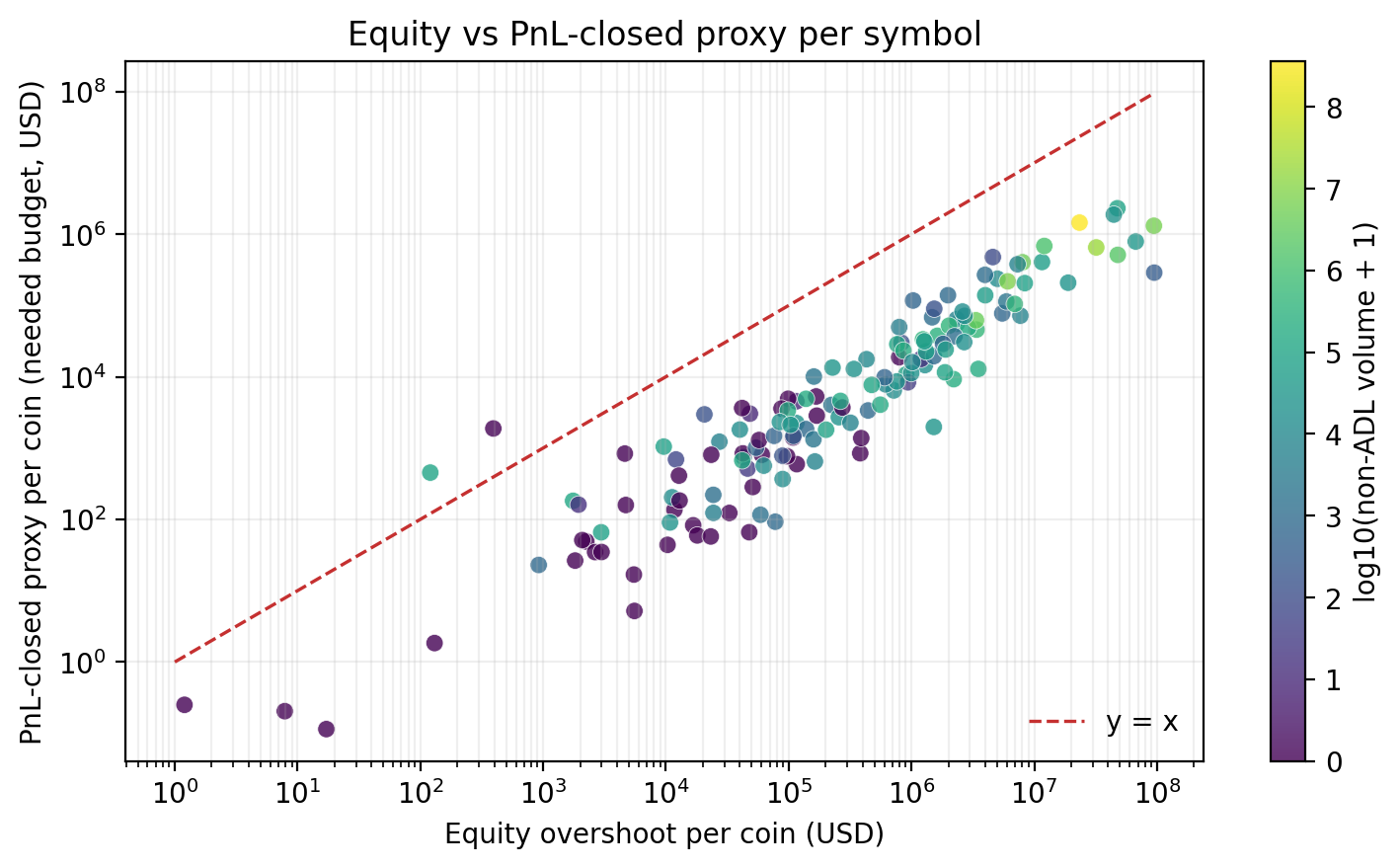

This confusion becomes visible when we compare equity-based capacity to PnL-based proxies.

Figure - Equity capacity vs PnL-based proxies

Each point represents a symbol. The dashed line indicates equality between equity-based capacity and a PnL-closed proxy. Large, systematic deviations show that entry-PnL materially understates how much loss the system can actually absorb.

The system does not haircut stories about where a position entered. It haircuts current equity state. Treating PnL as capacity silently invents seniority without tracking it.

If the answer is “entry PnL,” then the slogan is already false in an important way.

13. Why entry-PnL is the wrong variable (even if it feels right)

Entry PnL feels natural because humans think in stories: I entered here. Price moved there. This is my gain.

But mechanisms do not care about stories. They care about invariants.

Ask yourself this:

Can a trader reset their entry PnL without changing the system’s tail risk?

The answer is obviously yes.

A trader can close and reopen at the same price, split exposure across accounts, and rebalance across correlated instruments, and dramatically change their measured “profit” while leaving the exchange’s insolvency risk unchanged.

This tells you something fundamental:

Entry PnL is not a conserved quantity.

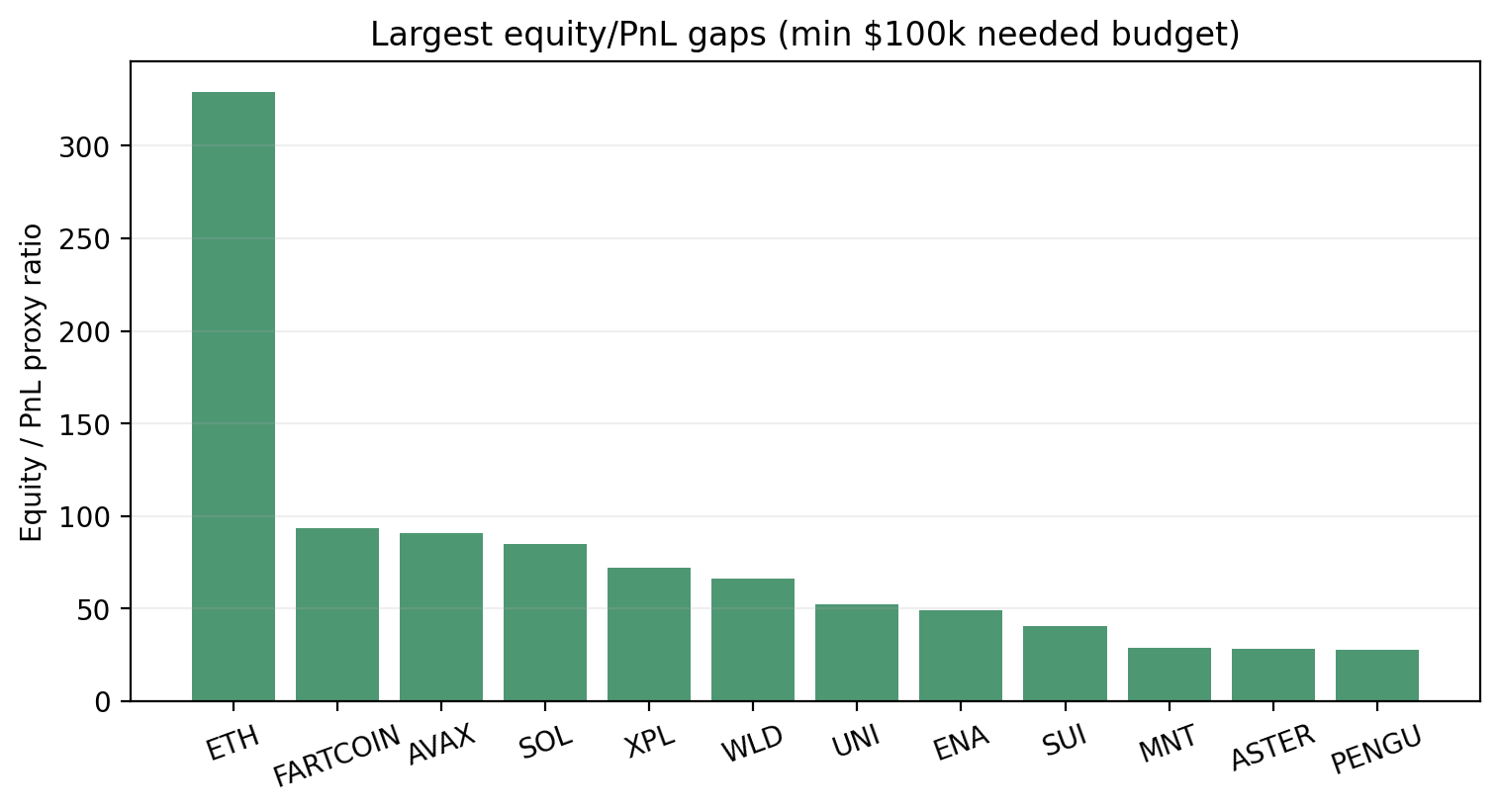

The mismatch between equity and PnL is not evenly distributed.

Figure - Largest equity–PnL gaps by symbol

A small number of symbols account for most of the gap between equity-based capacity and PnL-based proxies. Any allocation rule that relies on PnL therefore concentrates losses implicitly - but does so in a way that is misaligned with actual capacity.

This is why queue-based ADL feels violent: not because the rule is malicious, but because capacity itself is concentrated.

And anything that is not conserved, not invariant, is poison in a crisis mechanism.

From a rational perspective, this is the red flag. If the variable disappears when you re-label the system, it was never the right variable.

14. What “winnings before principal” actually means in math

If we strip the slogan of rhetoric, what it really claims is a seniority rule.

It says: there are layers of capital, and some layers are junior to others.

Let’s write that down.

For each account $i$, decompose equity into two parts:

\(e_i = p_i + g_i\) where:

- $p_i$ is principal (senior),

- $g_i$ is gains (junior).

Now the slogan “we only haircut profits” becomes a feasibility statement:

ADL may extract from $g_i$ freely, but may only touch $p_i$ if $\sum_i g_i$ is insufficient.

That is not moral language. That is a capacity constraint.

Immediately, a sharp inequality appears:

\[B \le \sum_{i \in W} g_i\]If this holds, then a “profits-only” ADL is feasible. If it fails, then no mechanism, queue, pro-rata, lottery, or divine intervention, can avoid touching principal or defaulting.

This is one of the most important equations in the entire ADL story, because it tells you when a promise becomes mathematically impossible.

15. The real mistake: treating seniority as interpretation instead of state

Most production systems do not actually track $g_i$ as a first-class variable.

Instead, they infer it indirectly from entry price, mark price, or recent trades.

That is a category error.

Seniority is not something you interpret after the fact. It is something you must persist as state.

If you do not track gains explicitly, then “winnings first” is not a rule, it is a post-hoc justification.

This is why entry-PnL-based queues feel unfair and gameable at the same time:

- unfair, because they violate the intuition of seniority under small perturbations,

- gameable, because traders can manipulate the proxy.

Both failures come from the same root cause: the wrong state variable.

16. The imagination fix: gains as a bucket, not a path

Here is the imaginative leap that fixes the problem.

Stop thinking of profit as “where you entered.” Start thinking of profit as a bucket that fills over time.

Whenever an account realizes gains, they go into a gain bucket $g_i$. Withdrawals reduce it. Losses reduce it. Crucially: closing and reopening does nothing to it.

You can even split this bucket into a small ladder, recent gains, older gains, deeply settled gains, each with explicit seniority.

Now ADL becomes clean:

- Try to raise $B$ from the most junior gain buckets.

- If exhausted, move up the seniority stack.

- Touch principal only if feasibility requires it.

At that point the slogan becomes true by construction, the gaming surface collapses, and fairness debates turn into capacity debates.

This is the kind of fix we love: change the representation, not the rule.

17. How seniority interacts with allocation rules

Once seniority is explicit, allocation rules become modular.

Within a seniority layer, you still need an allocation rule, queue (sparse, brittle), pro-rata (smooth), risk-weighted pro-rata (externality-aligned), or a hybrid.

The seniority ledger does not replace allocation. It constrains it.

Mathematically, you are now solving: \(\sum_{i \in W} h_i^{(g)} \le \sum_i g_i,\qquad \sum_{i \in W} h_i^{(g)} + h_i^{(p)} \ge B\) with $h^{(g)}$ exhausted before $h^{(p)}$.

That structure is what makes the mechanism honest.

18. Why this matters for revenue and trust

There is a subtle but critical side effect here.

When seniority is explicit:

- traders can reason about worst-case outcomes,

- hedging becomes possible,

- ADL becomes predictable rather than mysterious.

Predictability matters more for LTV than generosity.

Markets forgive losses. They do not forgive rules that feel arbitrary.

This is how seniority accounting quietly improves the $R$ leg of the trilemma without violating solvency.

19. A pause before the hard limits

At this point, it’s tempting to believe that with seniority ledgers and risk-weighted pro-rata, we have “solved” ADL.

We have not.

We have merely aligned the mechanism with reality.

The next section is where we confront the unavoidable limits, the inequalities that tell you why:

- some concentration is inevitable,

- overshoot cannot be eliminated under discrete execution,

- and why, sometimes, principal must be touched.

But now, when we derive those bounds, they will feel natural rather than disappointing.

20. Lower bounds you can feel

Up to now, we’ve been designing with imagination: reshaping how pain is distributed, making seniority explicit, replacing brittle rankings with smooth rules.

Now we do something more uncomfortable.

We ask: what cannot be avoided, no matter how clever the mechanism is?

This is where many ADL debates quietly collapse, because they confuse design choice with physical constraint.

21. Fairness caps are capacity constraints, not virtues

Suppose you make a strong fairness promise:

“No account will lose more than 20% of its available capacity in a single ADL wave.”

That sounds humane. It sounds reasonable.

Let’s translate it into math.

If $c_i$ is the maximum extractable amount from account $i$, your promise is: \(h_i \le \alpha c_i \quad \text{for all } i,\) with $\alpha = 0.2$.

Then the total amount you can raise is bounded: \(\sum_i h_i \le \alpha \sum_i c_i.\)

Now comes the moment of truth.

If the required budget satisfies: \(B > \alpha \sum_i c_i,\) then your promise is infeasible.

No allocation rule can satisfy it. Not queues. Not pro-rata. Not risk-weighted anything.

This inequality is the mathematical expression of a sentence every crisis engineer eventually learns:

You can’t promise softness if the shock is large enough.

This is why fairness is not a moral debate in ADL. It is a capacity planning problem.

22. “Profits only” has the same limit, just hidden

The same logic applies to seniority.

If you promise:

“We will only haircut gains, never principal,”

you are asserting: \(h_i \le g_i \quad \text{for all } i.\)

That implies: \(\sum_i h_i \le \sum_i g_i.\)

So feasibility requires: \(B \le \sum_i g_i.\)

This is not a critique of the promise. It is the condition under which the promise can be kept.

When that inequality fails, one of three things must happen:

- principal is touched,

- an external backstop is invoked,

- insolvency is accepted.

There is no fourth option.

This is why explicit seniority ledgers matter: they tell you when the promise breaks, instead of pretending it never will.

23. Why concentration is sometimes unavoidable

Now let’s confront the hardest emotional objection:

“Why do a few accounts always seem to get hit so hard?”

The answer is not “because the exchange chose violence.”

It is geometry.

In real markets, capacity $c_i$ is heavy-tailed. A small number of accounts hold a large fraction of unrealized gains or extractable equity.

Sort capacities: \(c_{(1)} \ge c_{(2)} \ge \dots \ge c_{(n)}.\)

Let $k$ be the smallest index such that: \(\sum_{j=1}^k c_{(j)} \ge B.\)

Then any feasible allocation, regardless of fairness objective, must extract at least: \(B - \sum_{j>k} c_{(j)}\) from the top $k$ accounts.

If the tail beyond $k$ is thin, concentration is forced.

Queues make this visible by wiping the top accounts outright. Pro-rata hides it by applying fractions, but the mass still comes from the same place.

This is why concentration is not always a failure of design. Sometimes it is a consequence of who can pay.

24. Overshoot is not theft, it’s granularity

Another frequent accusation during ADL events is:

“The system took more than it needed.”

Sometimes that is true. Often it is misunderstood.

Here’s the physical reason overshoot exists.

ADL is executed in contract space, not wealth space.

Contracts are discrete. Positions must be closed in integer or lot-sized units. Markets move during execution. Prices slip.

In an ideal continuous world, you could solve: \(\sum_i h_i = B\) exactly.

In the real world, you solve something closer to: \(\sum_i h_i \in {0, \Delta, 2\Delta, 3\Delta, \dots},\) where $\Delta$ is the effective granularity induced by execution.

So the best you can guarantee is: \(B \le \sum_i h_i < B + \Delta.\)

This bound is structural.

You can reduce $\Delta$ with:

- better rounding schemes,

- fixed-point scaling,

- partial closes,

- execution-aware allocation,

but you cannot make it zero without solving a mixed-integer optimization under stress, which is exactly why production systems avoid it.

This is why Tarun’s methodology is careful to separate:

- needed budget (the bankruptcy gap proxy),

- from production haircut (measured via two-pass counterfactuals).

Once you do that, overshoot becomes a measurable engineering artifact, not a moral scandal.

25. The trilemma, revisited, now without mysticism

Now we can restate the ADL trilemma without slogans.

- Solvency requires raising $B$ quickly, even under heavy tails and granularity.

- Fairness requires limiting concentration and gaming surfaces.

- Revenue/LTV requires predictability and trust.

The lower bounds we just derived show why you can’t maximize all three simultaneously in static designs.

But they also show something more important:

Good ADL design is not about escaping the trilemma. It is about choosing where the pain is unavoidable and where it is optional.

That’s a design problem, not a philosophical one.

26. What remains under our control

After all these constraints, what is left?

Quite a lot, actually.

You can still choose eligibility intelligently, align allocation with externality rather than history, make seniority explicit, reduce brittleness with smoothing and caps, and reduce overshoot with better rounding. The through-line is predictability.

Predictability is what converts losses into acceptable risk instead of betrayal.

27. The final reframing

ADL is not about fairness in the abstract.

It is about damage containment under unavoidable failure.

A bad mechanism hides that reality behind slogans. A good mechanism exposes it, quantifies it, and distributes it in the least destructive way possible.

That is the difference between a system people tolerate and one they abandon.

28. A production-grade ADL design menu

At this point, you should be slightly uncomfortable, but oriented.

We’ve seen that ADL is not a moral choice but a response to failure. We’ve seen that seniority is a capacity constraint, not a slogan. We’ve seen that concentration, overshoot, and pain are sometimes unavoidable.

So what does “better ADL” actually mean in practice?

It does not mean escaping the trilemma. It means designing mechanisms that behave well inside it.

What follows is not a list of fantasies. These are designs that survive contact with execution, incentives, and mathematics.

28.1 Start with eligibility, not allocation

The most important ADL decision happens before any math runs:

Who is even allowed to pay in this wave?

Eligibility determines:

- the size of $\sum c_i$,

- the feasibility of “profits-only” promises,

- and which cohorts internalize tail risk.

Good eligibility rules are:

- state-based (buffers, leverage, stress exposure),

- stable under small perturbations,

- hard to manipulate without changing real risk.

Bad eligibility rules are:

- path-dependent,

- resettable,

- sensitive to cosmetic actions like close/reopen.

This is where many exchanges lose trust without realizing it: they debate allocation rules while eligibility quietly encodes arbitrary targeting.

28.2 Use seniority ledgers to make promises honest

If the product narrative is “winnings are junior,” then gains must exist as a first-class state variable.

A seniority ledger does three things simultaneously:

- It turns slogans into inequalities.

- It collapses entire classes of gaming attacks.

- It tells you exactly when principal must be touched, instead of pretending it never will be.

Without explicit seniority, fairness debates are just arguments over proxies.

With it, they become engineering decisions.

28.3 Choose smoothness by default; sparsity only when forced

Queues should no longer be the default.

They are the correct solution only when the objective is sparsity:

- minimal number of touched accounts,

- maximal operational simplicity,

- fastest possible intervention.

Everywhere else, smoothness wins.

Pro-rata and its variants are not ideological choices. They are what you get when you penalize spikes and insist on invariance under relabeling and scaling.

This is the single most important shift in mindset:

Use queues when you want to touch few accounts. Use pro-rata when you want to control damage.

Once you say this explicitly, many design arguments evaporate.

28.4 Weight by externality, not history

Naïve pro-rata spreads pain but ignores responsibility.

The next step is not to return to queues, it is to change the measure.

Risk-weighted pro-rata is the cleanest production-grade move:

- distribute pain smoothly,

- bias it toward positions that contribute to tail insolvency,

- and do so using state variables that are hard to game.

This is where ADL starts to align incentives instead of just redistributing losses.

28.5 Hybrids are not compromises, they are realizations

In real systems, pure forms rarely survive.

Bucketed priority with pro-rata inside buckets, capped spreads, and tiered seniority rules are not “messy compromises.” They are what happens when you respect compute limits, you respect execution granularity, and you respect the lower bounds we derived.

The test of a hybrid mechanism is not elegance. It is whether its failure modes are predictable.

28.6 Treat execution as part of the mechanism

This cannot be emphasized enough:

If your allocation rule cannot be executed cleanly, it is not the mechanism.

Discrete contracts, partial fills, slippage, and latency are not implementation details. They shape overshoot, concentration, and perceived fairness.

This is why rounding schemes matter, fixed-point scaling matters, and execution-aware heuristics matter.

Overshoot is not theft. It is granularity. The only real question is whether you can bound it.

29. What “better than today” actually means

After all this, we can finally say what progress looks like.

A better ADL mechanism is not one that never hurts anyone, never concentrates losses, or never touches principal.

Those goals are mathematically incompatible with reality.

A better ADL mechanism is one that:

- fails gracefully,

- exposes its limits honestly,

- aligns burden with externality,

- and behaves predictably under stress.

Predictability is the hidden currency here.

Markets forgive losses. They do not forgive rules that feel arbitrary or manipulable.

30. The real success criterion

Here is a practical test of an ADL mechanism:

Can a sophisticated trader, before entering a position, reason about their worst-case ADL exposure without needing to guess how the exchange feels that day?

If the answer is yes, the mechanism has done its job.

Not because it is fair. But because it is intelligible.

31. Closing

ADL exists because markets are violent and discrete systems break under stress.

You cannot design that away.

What you can do is be explicit about the tradeoffs, make seniority a real ledger rather than a proxy, and treat execution as part of the mechanism rather than an afterthought.

Once you do that, the design space becomes finite, navigable, and, most importantly, improvable.

That is what imagination buys you when it is disciplined by math.

And that, ultimately, is what makes a system worth trusting.