Why the Carden Method Works (and What the Brain Has Been Trying to Tell Us)

I’m writing this for a personal reason: my seven-year-old lives in a world where answers are cheap. Watching him learn forced me to ask a harder question: if answers no longer matter, what does?

In the age of AI, producing an answer costs almost nothing. Verifying it still costs attention, judgment, and time. That’s the bottleneck. At a Carden workshop, a parent asked the question many parents are carrying around: if AI can generate answers instantly, what are we actually teaching? Another parent replied: verification. That’s the expensive part.

I want to understand learning the way an engineer understands a machine. Not what schools claim works, but what minds can actually do, and what kinds of classrooms protect curiosity instead of draining it. If a machine can hand a child plausible answers all day, the point is no longer recall. It’s whether the child can think, wonder, and keep the joy of learning intact.

A curious thing happens in some classrooms.

A child wakes up sick, feverish and clearly unwell. Any sensible parent keeps the child home. But the child protests, not because of missing friends or recess, but because of missing learning.

When I first heard that story in the workshop, I didn’t know whether to admire it or distrust it. Kids aren’t supposed to want to learn. Learning is supposed to be work. Fun is the reward, if you’re lucky.

So here’s the puzzle:

Why does learning feel magnetic for some children and brittle for others, anxious and fragile? Why do some students tense up at a new problem while others lean forward?

Intelligence doesn’t explain it. Motivation doesn’t explain it either.

The difference is often quieter: how the mind has been trained to meet uncertainty.

The Brain Is Not a Storage Device

We talk about learning as if the brain were a container: pour facts in, store them, retrieve them later. It’s a comforting metaphor. It suggests education is transfer: efficient input, periodic testing, onward.

But the brain wasn’t built to store facts.

It was built to move a body through the world.

It takes messy sensory input, makes a guess about what’s happening, checks reality, corrects itself, and acts. Learning is less like filing and more like updating a model.

Question: If that’s true, why does the brain remember anything at all?

Answer: Because some information changes behavior. If it helps the brain predict and act, it tends to stick. If it doesn’t get used, it fades.

That explains why memorized facts often evaporate after a test. The brain is economical. It keeps what seems useful and discards what doesn’t.

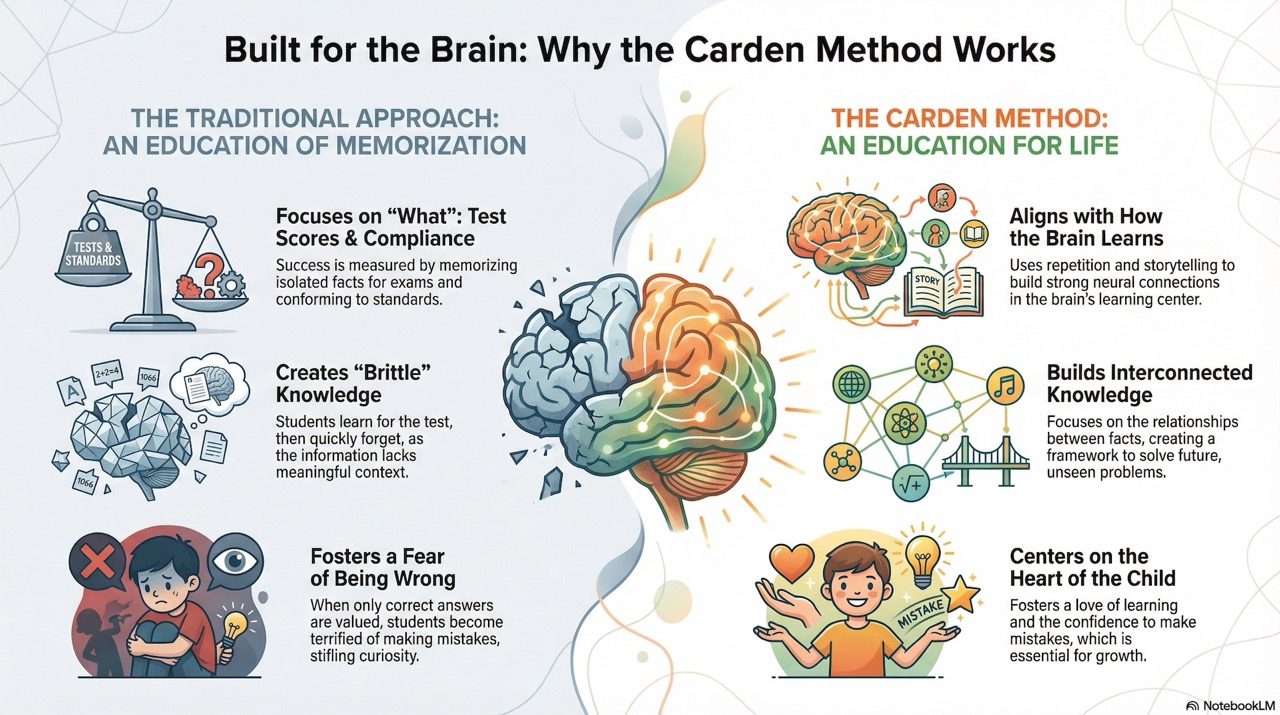

Why Memorization Feels Safe and Why It Fails

Memorization feels safe for a reason. It shrinks uncertainty. There’s no exploration, no risk, no need to be wrong. You either recall the answer or you don’t.

Question: If memorization is so fragile, why does it work so well in school?

Answer: Because school rewards it. The environment is stable enough that short-term recall can pass as mastery.

But the real test of learning isn’t whether you can answer what you’ve seen before. It’s what happens when the question changes, when the template is missing.

That’s the pivot. Some students panic. Others orient.

Returning Is Not Repeating

People say “practice makes perfect,” as if repetition were the main ingredient. But most of us have repeated something many times and still lost it.

The brain responds less to repetition than to return.

Returning means meeting the same idea again, but in a way that demands slightly new work. Same concept, different coat. That tells the brain, this wasn’t a one-time performance; it’s a tool.

A child learns a letter’s shape, then its sound, then how it behaves in words, then how those words behave in sentences. Each return deepens the model.

Question: Why does variation matter so much?

Answer: Because variation forces structure. A fact that survives variation becomes usable knowledge. A fact that only works in one format stays brittle.

Making Differences Sharp

In the workshop, a speaker drew a letter b and said: “If I just tell a child this is b, it’s a cold symbol. But if I say it’s the sting of the bee and the body of the bee, the order is no longer arbitrary.”

Suddenly the b/d problem stops being a geometry puzzle and becomes a character difference.

That matters because one hard job in early learning is telling apart things that are similar but not the same. When instruction blurs distinctions, the brain blurs them too. Confusion follows.

Question: Why do small confusions persist for years?

Answer: Because once two things are encoded as “almost the same,” every future encounter reinforces the overlap. You don’t fix it by going faster. You fix it by making the differences crisp.

Why Fear Breaks Learning

Learning is error-correction. You predict, you’re wrong, you update. If errors are dangerous, the loop collapses.

In classrooms, danger is rarely physical. It’s social: embarrassment, comparison, humiliation, the dread of being wrong in public. When mistakes feel costly, exploration stops. The mind narrows.

In the second lecture, Mr. Reed called this brittle education. If you’re terrified of being wrong, memorization becomes the safest move.

Question: Is “willingness to be wrong” just a classroom virtue?

Answer: No. It’s a requirement. Without safe error, the brain can’t update its model. Without updates, you get performance, not learning.

Making Skills Cheap

Once you see the constraints, limited attention, limited working memory, the need for safe error, the Carden classroom starts to look less like a philosophy and more like an engineered system.

The first move is to make foundational skills cheap: decoding, handwriting, arithmetic facts, sentence structure.

Small steps. Frequent practice. Immediate correction. Cumulative review.

Question: Isn’t this just drill?

Answer: Drill is mindless repetition. This is load management. The goal isn’t to keep kids busy; it’s to remove friction so the mind can do higher work.

One speaker used a cycling analogy: nobody wins a race while consciously thinking about balance. Balance has to be automatic so attention can go to the road.

Language as the Skeleton of Thought

Many students “struggle with math” when the failure is actually linguistic: misreading the question, misunderstanding relationships, failing to translate words into structure.

Carden treats language as infrastructure. Students explain problems in clear sentences before manipulating symbols.

Question: Why insist on complete sentences?

Answer: Because sloppy language produces sloppy models. If a student can’t state the problem cleanly, they can’t solve it reliably.

Imagination Is Not Decoration

Imagination is often treated as a reward. Carden treats it as a cognitive tool.

Letters become characters. Shapes gain hooks. Confusion drops because representations stop overlapping.

The same logic shows up in reading. Early Carden readers famously have no pictures. At first this sounds harsh. But the intent is simple: the child must generate the scene internally.

A word becomes not a symbol but an experience.

Question: Why does that matter?

Answer: Because comprehension is simulation. If the child can’t “see” what the sentence is doing, reading becomes word-calling. If they can, reading becomes meaning.

Reading as Flow, Not Word-Calling

Reading isn’t saying words aloud. It’s moving through meaning.

Fluency and phrasing matter because meaning lives in connected structure. When decoding is choppy, understanding is too.

The exact sequencing of phonics elements is a pedagogical choice. The principle underneath it is simpler: comprehension rides on flow.

What Kind of Learner Emerges

The real test of education is not performance under familiar conditions. It’s behavior under novelty.

A memorization-trained student asks, Have I seen this exact problem before? A model-trained student asks, What is this like? Where do I start?

That difference is orientation.

And orientation is what matters in an AI world. When answers are cheap, verification is rare.

Control of Tools, Not Submission to Them

When skills aren’t automatic, students are controlled by their tools. Reading consumes attention instead of serving it. Writing exhausts effort instead of expressing thought.

When tools are reliable, students gain trust that their skills will show up when needed. That trust invites risk. Risk invites learning.

The Willingness to Be Wrong

A child trained in a shame-free error environment doesn’t treat mistakes as identity. Being wrong isn’t a verdict; it’s data.

Question: Why is that such a big deal?

Answer: Because uncertainty is where real thinking begins. If a child can’t stand uncertainty, they can’t think. They can only perform.

The Center of Gravity

The final image from the lecture was a roller coaster.

Old coasters were built around the track. Riders endured whatever forces the track imposed. Modern coasters shift the center of gravity to the rider’s chest. The forces can be greater, and the experience is smoother.

Traditional education centers the track: curriculum first, child adapts. Carden centers the rider: the system moves with the child.

Not to reduce rigor, but to make rigor survivable.

Imagination Beats Knowledge

Knowledge is what you recall when the question is familiar. Imagination is what lets you act when the question is new.

Education shouldn’t eliminate uncertainty. It should prepare the mind to meet uncertainty with clarity, courage, and tools.

The Carden Method’s achievement isn’t better answers.

It’s better learners: learners who can move.

Appendix A

Biological Foundations of Learning

(Based on Lecture 1 by Dr. Sipla, neuroanatomist and Carden alumnus)

This appendix summarizes the biological claims from the first lecture and ties them to mainstream neuroscience. The goal isn’t terminology. It’s the few mechanisms that matter for learning, and why Carden’s choices line up with them.

A.1 The Brain’s Primary Job: Generating Action

A useful starting point:

The brain did not evolve to store facts. It evolved to generate behavior.

From a biological perspective, perception, memory, and reasoning exist to support action, moving the body through the world. Learning is about improving prediction.

The brain continuously:

- forms predictions about the world,

- compares them to incoming sensory data,

- updates its internal models when errors occur.

Information that improves prediction is retained. Information that doesn’t get used is gradually discarded.

A.2 A Minimal Tour of Relevant Brain Regions

Only a small subset of neuroanatomy is needed to understand the learning claims made in the lecture.

Occipital Cortex - Visual Input

Processes raw visual information (shapes, lines, contrast). Relevant for early letter and symbol recognition.

Parietal Cortex - Spatial and Sensory Integration

Supports spatial relationships (“where”), magnitude, and orientation. Relevant for handwriting, geometry, and number sense.

Temporal Cortex - Object and Language Recognition

Involved in identifying “what” things are, including words, sounds, and meaning. Central for language comprehension and reading.

Frontal Cortex - Planning and Executive Control

Supports decision-making, sequencing, monitoring errors, and voluntary action. Heavily involved when learners explain reasoning or solve novel problems.

Hippocampus - Contextual Binding and Learning

Located within the temporal lobe. Plays a key role in:

- forming new declarative memories,

- binding together what/where/when,

- detecting novelty and relevance.

The hippocampus doesn’t store everything. It helps decide what gets integrated into broader cortical networks.

A.3 Pattern Separation and Why Confusion Happens

One of the hippocampus’s core functions is pattern separation: distinguishing stimuli that are similar but meaningfully different.

This matters in early education:

- letters with similar shapes (b/d/p/q),

- words with similar sounds,

- concepts that differ subtly.

When instruction fails to highlight differences, the brain can encode overlapping representations, leading to persistent confusion. That confusion is often a discrimination problem, not an intelligence problem.

Teaching strategies that emphasize distinctiveness through contrast, structure, or story support clean separation.

A.4 Recursion, Not Repetition

The lecture emphasizes that durable learning requires regular recursion, not simple repetition.

Biologically, this matches how the brain treats importance:

- repetition in identical form signals familiarity,

- return in varied contexts signals relevance.

When information keeps returning and keeps mattering, it becomes:

- faster to access,

- more automatic,

- less dependent on effortful recall.

This shift is gradual.

A.5 Automaticity and Cognitive Load

As skills consolidate, they require less conscious control. This transition matters because working memory is limited.

When basic skills consume working memory, higher-order thinking becomes difficult. When basics are automatic:

- cognitive load drops,

- attention is freed,

- the learner can reason, plan, and abstract.

This is the biological rationale for early emphasis on fluency and accuracy: not as an end, but as a gateway.

A.6 Emotion, Relevance, and Learning Priority

Learning isn’t emotionally neutral.

The brain prioritizes information based on relevance to goals, emotional salience, and social context. Face-to-face teaching, storytelling, and meaningful interaction can raise engagement and attention.

The useful general principle is simple:

Learning improves with challenge plus safety.

Too much stress narrows attention and discourages exploration. Too little engagement leads to indifference.

A.7 Early Plasticity and Foundational Organization

Early childhood is marked by high neural plasticity. There’s no sharp cutoff, but the early years are efficient for:

- language acquisition,

- pattern discrimination,

- habit formation.

Foundational skills learned early often require less remediation later because early organization reduces future load.

A.8 Summary of Biological Claims (Plain Version)

From a neuroscience perspective, the strongest claims supporting the Carden Method are:

- learning sticks when it supports prediction and action,

- durable knowledge needs return-with-variation,

- automaticity frees working memory for thinking,

- clear discrimination prevents persistent confusion,

- safety supports exploration and error-based updating,

- early organization reduces later remediation.

Closing Note — Appendix A

Carden doesn’t “hack” the brain. It works because it respects how learning systems behave: limited bandwidth, strong sensitivity to fear, and a need for meaning and practice that returns.

Appendix B

Educational Philosophy and Method

(Based on Lecture 2 by Mr. Joel Reed, head of school at The Howard School; lifelong Carden learner and master teacher)

This appendix summarizes the philosophical foundations and the classroom design choices described in the second lecture.

B.1 The Problem with “Brittle” Education

A brittle educational system performs well under narrow conditions but fails under variation. Students may succeed when:

- questions are familiar,

- procedures are rehearsed,

- evaluation criteria are explicit.

Performance collapses when:

- problems are phrased differently,

- ideas must be combined,

- there is no template.

Brittleness is often produced by over-optimizing for compliance and recall, instead of understanding and adaptability.

B.2 Redefining Success

In the Carden philosophy, success is not speed through material or test performance alone.

A successful student:

- controls the tools of learning rather than being controlled by them,

- approaches new problems with confidence rather than avoidance,

- is willing to be wrong in order to become right.

This shifts the goal from outcomes to capacity: not “knowing more answers,” but being able to get answers when needed.

B.3 The Center of Gravity Metaphor

The lecture used a roller coaster metaphor.

Early roller coasters were engineered around the track. The rider absorbed whatever forces the track imposed. Modern coasters shifted their center of gravity to the rider’s chest. That change allowed greater forces with a smoother ride.

Mapped to education:

- traditional systems center the curriculum,

- Carden centers the learner.

This doesn’t remove rigor. It makes rigor sustainable.

B.4 Sequential Steps and Skill Automation

Carden breaks learning into small, sequential, interrelated steps. This:

- reduces overload,

- supports automation of basics.

The cycling analogy applies: balance must be automated so attention can go to strategy and environment. When decoding, handwriting, and basic arithmetic become reliable, attention can move to comprehension and reasoning.

B.5 Language as the First Problem Space

The lecture argues that many struggles, especially in math, are language failures:

- misreading what’s asked,

- missing relationships,

- failing to translate symbols into meaning.

Carden responds by requiring:

- complete, precise sentences,

- problem explanations in natural language before symbols.

Language is treated as the skeleton of thought.

B.6 Letters as Stories: “Play Names”

Carden introduces letters using narrative “play names” that give each symbol a distinct identity:

- B as “the sting of the bee and the body of the bee,”

- D as a dog whose ear stands up when patted.

These stories reduce ambiguity, prevent reversals, and anchor abstract shapes in concrete meaning.

B.7 Rhythm and the Structure of Reading

Reading is treated as rhythmic, not merely decoding. Smooth phrasing and continuity are emphasized early. Whatever the sequencing choices, the guiding idea is:

Comprehension depends on flow.

B.8 The Mental Image

Early Carden readers often have no illustrations. That is intentional. Students must construct mental images while reading. Meaning is generated internally, not supplied visually.

B.9 The Willingness to Be Wrong

A central commitment is normalizing error. By correcting mistakes calmly and treating errors as information, the system preserves exploration. This stands in contrast to fear-driven classrooms where error leads to memorization and avoidance.

B.10 Summary of Commitments

Carden is built around a few commitments:

- learning is model-building, not answer storage,

- structure enables freedom,

- automaticity supports understanding,

- imagination is a tool,

- safety is a prerequisite for intellectual risk,

- education should produce adaptive learners, not just performers.

Appendix C

Mapping the Carden Method to Learning Science

(With confidence levels and caution flags)

This appendix maps specific Carden practices to established ideas from cognitive science and learning research. The point is not “Carden invented this.” It’s whether the practice lines up with robust constraints of human learning.

C.1 Core Mapping Table

| Carden Practice | Underlying Principle | What Research Commonly Supports | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small sequential steps | Cognitive load management | Working memory is limited; reducing load helps | High |

| Daily cumulative review | Retrieval + spacing effects | Retrieval strengthens long-term retention | High |

| Automation of basics | Automaticity | Fluency enables higher-order reasoning | High |

| Immediate correction | Error-based updating | Timely feedback improves updating | High |

| Willingness to be wrong | Psychological safety | Fear impairs exploration and learning | High |

| Language-first problem solving | Linguistic scaffolding | Many “math” failures are parsing failures | High |

| Play names | Distinctiveness/encoding | Rich cues reduce interference | High |

| Mental image reading | Generative processing | Generating meaning improves comprehension | High |

| Minimal illustrations | Reduced scaffolding | Internal construction can deepen learning | Medium–High |

| Rhythm-focused reading | Prosodic fluency | Fluency correlates with comprehension | Medium |

| Long vowels taught first | Sequencing choice | Order affects early fluency | Medium |

| Early intensive foundations | Early plasticity | Early structure often reduces remediation | Medium–High |

| Storytelling/rapport | Engagement | Social context can increase attention | Medium |

C.2 What “High Confidence” Means Here

High confidence doesn’t mean the practice is unique to Carden or explained down to molecules. It means the direction of effect is supported across many studies and contexts.

C.3 Pedagogy vs. Neuroscience (Keep This Straight)

Some explanations, especially those involving specific neurotransmitters or hard age cutoffs, should be taken as teaching metaphors unless they come with evidence. That doesn’t sink the method. Good educators often find what works first, then search for better explanations later.

C.4 Why It Works Without Fancy Brain Claims

You can explain most of Carden’s effectiveness with a short list:

- working memory is limited,

- retrieval beats exposure,

- automaticity frees attention for thinking,

- fear shuts down exploration,

- distinctiveness prevents confusion,

- meaning and use beat isolated facts.

Any system that respects these constraints tends to beat one that ignores them.

C.5 Where Reasonable Disagreement Can Exist

Educators can disagree about:

- sequencing,

- pacing,

- how much structure is ideal for a given child,

- how much external scaffolding to provide.

Those are design choices. The non-negotiables are monitoring confusion, avoiding fear-based compliance, and protecting curiosity.

C.6 Bottom Line

Carden’s advantage is coherence. Many programs do one or two pieces well. Carden stacks several learning-friendly choices into one system.

Appendix D

What the Carden Method Is Not

When a learning system works, observers often project familiar categories onto it. This appendix clarifies what Carden isn’t, based on the philosophy and classroom practices described in the lectures.

D.1 It Is Not Test Preparation

Carden does not optimize for test formats as a primary goal. Students may do well on tests, but the system is aimed at transferable skills, not rehearsed templates.

D.2 It Is Not Rote Memorization

Practice is used, but the goal is not reciting facts. Concepts return in context and deepen over time. Memorization without use is treated as fragile.

D.3 It Is Not Unstructured Discovery-Only Learning

Carden doesn’t assume beginners will discover foundational structure on their own. It treats structure as a scaffold: necessary early, internalized gradually, then made invisible.

D.4 It Is Not Authoritarian or Fear-Based

Carden classrooms are structured and teacher-led, but the structure isn’t enforced through shame. Errors are corrected without public punishment.

D.5 It Is Not Anti-Creativity

The method delays some unstructured expression until tools are reliable. Creativity without tools often becomes frustration. Creativity with tools becomes freedom.

D.6 It Is Not a Neuroscience “Hack”

Carden doesn’t require secret brain tricks to work. The method succeeds by respecting basic constraints: limited bandwidth, the need for retrieval and automaticity, and the fragility caused by fear.

D.7 It Is Not One-Size-Fits-All

The method still depends on pacing, attentive teaching, and judgment. No system is optimal for every child in every context.

D.8 It Is Not a Guarantee

Learning still takes work. The difference is the kind of work: purposeful rather than performative, challenging without being threatening, demanding without being demeaning.