Tarun Chitra’s ADL paper triggered a big argument around Hyperliquid’s October 10–11 event1234.

Who’s right about what, and what actually needs fixing?

The ADL debate around Hyperliquid’s October 10–11 event has three main characters:

- Hyperliquid, whose ADL is implemented in contracts and described only briefly in docs5.

- Tarun’s paper, which models ADL in wealth space (equity haircuts and fairness metrics) and claims queues like Hyperliquid’s waste a lot of “good PnL.”

- Dan Robinson, who says the paper’s central model of Hyperliquid ADL is just wrong.

Most readers want answers to one basic question: who is right about what? Let’s start there.

1. Scoreboard: where Dan is right, where Tarun is right

Very short version:

-

Dan is right that:

- Hyperliquid’s ADL works in contracts, not as “take 100% of each winner’s equity in order.”

- The paper’s Pro-Rata mechanism, as written, lives in equity space, while live systems like Drift allocate losses by position size (contracts)6.

- The USD 653m “excess haircuts” number needs a clear, public methodology so that others can audit and verify it.

-

Tarun is right that:

- ADL is fundamentally about redistributing wealth when bad debt appears, and queue-style rules can concentrate that burden on a small set of winners.

- You can and should formalize this as haircuts on equity $e_T(p)$ and compare policies (queue vs pro-rata vs “smart” variants) using fairness metrics.

- Without open ADL code, everyone is inferring from behavior and docs; that uncertainty should be part of the conversation.

What, in my POV, actually needs editing in the paper:

- Label the queue model as an equity-space abstraction, not “the Hyperliquid queue.”

- Write Pro-Rata cleanly as a single scalar equity haircut and separate it from Drift’s contracts-pro-rata.

- Publish the analysis code (Tarun already hinted he would open source it next week) that yields USD 653m, and state clearly what “haircut” means in dollars.

Now some context, because the ADL design problem isn’t just crypto drama. ADL is an essential safety mechanism in high-leverage derivatives markets.

2. What ADL is for in practice

ak0 summarized the tradfi view neatly: ADL combines two older tools7:

- Tear-ups: forcibly close positions against those on the other side to stop losses.

- Variation margin gains haircutting (VMGH): take money from winners to cover bad debt when losers cannot pay.

Any margin venue has to solve two problems:

- Stop continued losses once margin is exhausted.

- Cover bad debt when “send lawyer, send sheriff” is not enough.

If you do nothing, bad debt lands on the venue or on non-defaulting traders in uncontrolled ways. If you push all losses onto brokers’ capital (the FCM model), brokers respond by slashing leverage and liquidity.

So exchanges end up with a kind of trilemma:

- How much to de-risk high-leverage accounts (tear-ups)?

- How much to haircut winners to cover tail losses (VMGH-like ADL)?

- How much capital efficiency and leverage they want to preserve?

The queue vs Pro-Rata debate is about the shape of that haircut: who exactly pays when bad debt appears.

That’s the backdrop. Now back to the specific fight.

3. Dan vs Tarun on the Hyperliquid queue

3.1 What Hyperliquid’s docs actually say

Hyperliquid describes ADL roughly as5:

- compute a priority index per position (something like PnL × leverage ÷ account value),

- sort open positions by this index,

- when there is bad debt, fully closed positions at a mark / ADL price in that order until enough opposite-side contracts have been matched.

“Closed” in Hyperliquid’s ADL means the position’s contracts are offset against bad debt, not that equity is zeroed. Equity loss depends on the PnL of the closed contracts.

Tarun’s queue uses PnL × leverage for clarity; Hyperliquid’s index is a close variant but includes entry price normalization.

Key point: this is all phrased in terms of contracts and positions being closed.

Dan’s simple example makes that concrete:

- A user with a 2 ETH short blows up; there is a USD 1,500 deficit.

- The top account in the ADL queue has a 1 ETH long, worth USD 3,000 with USD 1,500 in equity (2x levered).

In a contracts-based queue:

- The system needs to offset 2 ETH of bad short.

- The top long contributes its 1 ETH, so it eats half the loss (say USD 750).

- The other USD 750 comes from the next long(s) in the queue.

This top account is fully closed in contracts, but it has not had a 100% equity haircut. It lost a fraction of its equity.

3.2 What Tarun’s queue model actually does

The paper1 is written in wealth space. Each position $p$ has equity at time $T$:

\[e_T(p) = c + \mathrm{PNL}_T(p),\]with $c$ collateral and $\mathrm{PNL}_T(p)$ the realized profit or loss.

Over all positions $P_n$:

Total shortfall (bad debt) is

\[D_T(P_n) = \sum_{p \in P_n} (-e_T(p))_+,\]Total winners’ equity is

\[W_T(P_n) = \sum_{p \in P_n} (e_T(p))_+.\]An ADL policy $\pi$ is modeled as:

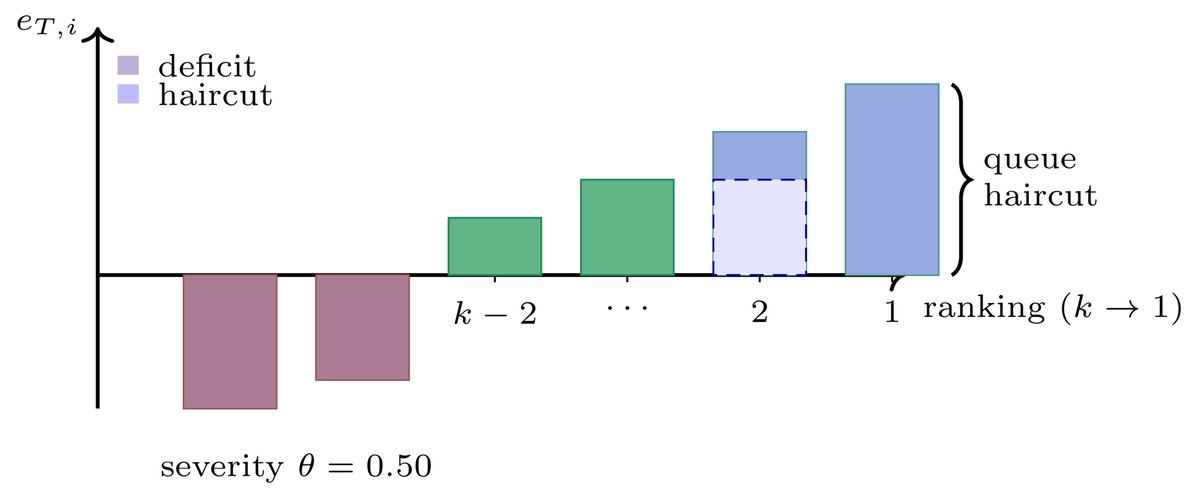

-

a severity $\theta^\pi \in [0,1]$ which chooses a budget

\[B = \theta^\pi D_T(P_n),\] -

a haircut fraction $h^\pi(p)$ for each position with $e_T(p) > 0$.

Post-ADL equity of a winner:

\[e_T^{\text{post}}(p) = (1 - h^\pi(p)), e_T(p).\]The queue policy $\pi^Q$ used in the theory is a greedy “water-filling” in equity:

- Sort winners by a score $s_T(p)$ (for example, PnL x leverage).

-

Walk this order and fill the budget $B$ by:

- setting $h^{\pi^Q}(p) = 1$ (take all equity) for some top winners,

- assigning a fractional $h^{\pi^Q}(p) \in (0,1)$ to one marginal winner,

- leaving the rest with $h^{\pi^Q}(p) = 0$.

This is the picture with solid bars of equity and a single shaded cap.

You can already see the gap:

- Hyperliquid: queue in contracts; fully closed positions may lose some fraction of equity.

- Paper: queue in equity; a “hit” from the queue means “take all equity from this account at this time snapshot,” unless it is the marginal partial bar.

Dan is right that if you read the queue in the paper as “this is Hyperliquid,” you get the wrong behavior for examples like the 2 ETH / 1 ETH case.

3.3 How to connect them without pretending they’re the same

The right way, IMHO, is to connect production ADL (contracts) and the paper’s model (equity) is to derive haircuts from observed equity changes, not to assume “closed ⇒ $h=1$.” But until we can see the full code on Hyperliquid ADL, we can’t know for sure. We can only make good guesses.

For a given ADL wave $t$:

- let $e_t(p)$ be equity at the start of the wave,

- define $e_t^{\text{no-ADL}}(p)$ as the equity at the end of the wave if ADL were disabled but the underlying price path and non-ADL order flow were the same,

- define $e_t^{\text{ADL}}(p)$ as the equity at the end of the wave with ADL active.

Then define a realized wealth-space haircut:

\[h_t^{\text{prod}}(p) = \begin{cases} \dfrac{e_t^{\text{no-ADL}}(p) - e_t^{\text{ADL}}(p)}{e_t(p)}, & e_t(p) > 0, \\ -1, & e_t(p) < 0 \text{ and the position is fully reset}, \\ 0, & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases}\]Total wealth taken from winners that wave:

\[H_t^{\text{prod}} = \sum_{p} h_t^{\text{prod}}(p), e_t(p)^+ = \sum_{p} \bigl(e_t^{\text{no-ADL}}(p) - e_t^{\text{ADL}}(p)\bigr)_+.\]Now:

- If Hyperliquid closes a 1 ETH long and that reduces equity by USD 750, then $h_t^{\text{prod}}(p)$ is USD 750 divided by the starting equity, not $1$.

- This matters a lot for any statistic that sums “haircuts in dollars” over many waves.

So the clean position is:

- Yes, the queue in the theory is an equity-space abstraction and does not reproduce Hyperliquid’s contracts-space queue.

- The paper should say that clearly and treat Hyperliquid’s actual ADL as data that induces $h_t^{\text{prod}}$, not as a literal instance of the theoretical $\pi^Q$.

Tarun’s “round vs not round” comment (integer vs continuous water-filling) fits inside this picture: you can still talk about “rounded queue” vs “continuous queue,” but you need to be explicit whether you are rounding contracts or equity4.

4. Pro-Rata: equity vs contracts, and what Drift actually does

Dan’s second complaint is that the paper “misdescribes Pro-Rata ADL” and that the Drift code Tarun links does not match the paper’s formula4.

4.1 Drift is contracts-pro-rata

In Drift’s implementation, socialized losses look like this in spirit:

- compute total loss $L$ on one side of the book,

- compute total base asset $\sum_i q_i$ on that side,

- define a per-contract loss

- charge each trader

That is base-space Pro-Rata: loss per trader is proportional to number of contracts $q_i$.

4.2 The paper’s fairness model is wealth-space

The fairness section of Tarun’s paper is based on how equity is redistributed, not how many contracts each account holds. It uses quantities like:

- $D_T(P_n) = \sum_p (-e_T(p))_+$, total shortfall,

- $W_T(P_n) = \sum_p (e_T(p))_+$, total winners’ equity,

and fairness metrics that compare the distribution of $e_T(p)$ across accounts.

In that world, the natural Pro-Rata benchmark is:

- each winner loses the same fraction of equity $\lambda_T$.

Written cleanly:

- severity $\theta^{\pi^{PR}} \in [0,1]$,

- global haircut fraction

- haircuts

- post-ADL equity for winners

Total haircut on winners:

\[\sum_{p} h^{\pi^{PR}}(p)\, e_T(p)^+ = \lambda_T\, W_T(P_n) = \theta^{\pi^{PR}} D_T(P_n).\]whenever $\theta^{\pi^{PR}} D_T(P_n) \le W_T(P_n)$.

That is Pro-Rata in equity. It is not what Drift does.

4.3 Two numeraires, two “Pro-Ratas”

Once spelled out, the distinction is straightforward:

- Drift / Dan: Pro-Rata in base space, losses $\propto q_i$.

- Paper: Pro-Rata in wealth space, losses $\propto e_T(p_i)$ via a common fraction.

Both are internally consistent. They answer different fairness questions:

- “Should two accounts with the same contract size take the same dollar loss, even if one is barely solvent and one is very rich?” (base-space)

- “Should two accounts with the same equity take the same fractional loss, even if one holds more contracts?” (wealth-space)

What the paper should not do is:

- cite Drift as a direct example,

- write an opaque Pro-Rata equation that looks equity-based,

- and leave readers thinking they are the same mechanism.

The fix is simple: use the scalar-$\lambda$ formulation above and state clearly that Drift’s implementation is base-space while the fairness model here is wealth-space.

5. The USD 653m “excess haircuts”: structure vs scale

The USD 653m claim is the most visible number in the paper and the least documented. Dan’s question is: “What exactly did you sum to get that value?”

Tarun has said the analysis code will be open-sourced within the next few days/weeks. Within the wealth-space model, a sensible pipeline for one ADL wave $t$ would be:

-

Shortfall. From starting equities $e_t(p)$ over $P_n^{(t)}$: \(D_t = \sum_{p} (-e_t(p))_+.\)

-

Production haircuts. From $e_t^{\text{ADL}}(p)$ and $e_t^{\text{no-ADL}}(p)$, compute \(\Delta e_{t,i} = e_t^{\text{no-ADL}}(p_i) - e_t^{\text{ADL}}(p_i),\) and \(H_t^{\text{queue}} = \sum_i \Delta e_{t,i}.\)

-

Optimal comparator. Over a policy family $\Pi$ (e.g. Pro-Rata or “Smart Queue”), solve \(H_t^\star = \min_{\pi \in \Pi} \sum_i h_t^\pi(p_i), e_t(p_i)^+\) subject to \(\sum_i h_t^\pi(p_i), e_t(p_i)^+ \ge D_t, \quad h_t^\pi(p_i) \in [0,1].\)

-

Utilization and excess haircuts.

\[\kappa_t = \frac{H_t^{\text{queue}}}{H_t^\star}, \qquad E_t = H_t^{\text{queue}} - H_t^\star.\]

Sum $E_t$ over all waves on October 10–11 to get the aggregate “excess haircuts” number; compare $\sum_t H_t^{\text{queue}}$ to $\sum_t D_t$ or $\sum_t H_t^\star$ to get the reported factor near $28$.

If the actual implementation did something like:

- $H_t^{\text{queue}} = \sum \text{notional}_i$, or

- $H_t^{\text{queue}} = \sum e_t(p_i)^+$ over all ADLed winners,

then it is not measuring “wealth lost.” It is measuring volume or gross equity, which could easily produce a number on the order of USD 653m but does not mean “traders paid USD 653m.”

So:

- The structure of comparing production ADL to a benchmark policy on the same event is sound.

- The scale of USD 653m is uncertain until the code is public and the “haircut” variable is clearly defined.

The USD 653m figure only reflects ‘excess wealth destruction’ if $H_t^{\text{queue}}$ measures actual equity lost, not notional contracts closed.”

6. Where this leaves the debate

From the perspective of someone reading both Dan and Tarun:

- Dan is correct to insist on the right units: contracts vs equity, and base-space vs wealth-space Pro-Rata.

- Tarun is correct that ADL is ultimately about who eats the loss when bad debt appears, and that queue-style schemes can concentrate that burden in ways that are worth formalizing.

The paper would become a lot harder to attack (and a lot easier to learn from) with a few targeted edits:

-

Explicitly label the queue abstraction. Say: “We work with a wealth-space queue that shares the same ranking idea as Binance/Hyperliquid, but does not reproduce their contract-level details. For Hyperliquid we reconstruct induced haircuts from data.”

-

Clean up Pro-Rata. Replace the current Pro-Rata equation with the scalar–$\lambda$ version above. State plainly that Drift implements base-space Pro-Rata, while the fairness section uses wealth-space Pro-Rata.

-

Publish and document the USD 653m analysis. Include a short methods summary in the paper that defines $D_t$, $H_t^{\text{queue}}$, $H_t^\star$, and shows one end-to-end wave reconstruction.

-

Adjust the language around Hyperliquid. Instead of “Hyperliquid wiped USD 653m of PnL,” say something like:

“Under our wealth-space reconstruction of the October 10 event, the induced queue concentrates haircuts on a small set of winners and appears to over-use their equity by a factor of about $\kappa$ relative to [specified benchmark].”

That keeps the main message intact:

- ADL is a necessary evil in leveraged systems.

- There are different ways to design it (queue vs Pro-Rata vs hybrids).

- Those choices create different maps from bad debt to who pays.

What this debate has surfaced is that it is not enough to say “we have ADL, trust us.” If you want to claim your design is fair and efficient, you have to be very clear about:

- what space you are working in (contracts or equity),

- how you model Pro-Rata,

- and exactly what you mean by “haircut” when you write down big dollar numbers.