How 1–5% reinvestment can create circularity, amplification, and cascades - without invoking accounting round-tripping

Jensen Huang, CEO of NVIDIA, gets asked a question that sounds almost silly until you try to answer it.

He’s talking about Nvidia investing a low single-digit percentage into AI companies and partners, and the interviewer pushes on circularity and systemic risk. Jensen’s reaction, in plain language, is: How could that possibly matter? It’s a tiny fraction. It can’t be the thing driving the whole machine.

That response has a familiar smell to anyone who has done physics.

It’s the smell of reasoning by size.

And physics is full of cases where reasoning by size is exactly how you miss the phenomenon. The classic one is the microphone squeal. The “cause” looks microscopic: a thin leak of sound from the speaker back into the mic. But the room fills with an aggressive shriek anyway. If you fixate on the leak, you’ll sound sensible and be wrong. The right question isn’t “how big is the leak?” The right question is “what is the gain around the loop?”

That is the only honest way to answer Jensen’s question. Not by arguing about whether 3% investment is “small,” but by asking whether the system is damped or amplifying.

Before we touch the equations of the physics of small reinvestment, one clean boundary, because the intellectual hygiene matters.

This post is not about accounting circularity. We are not talking about round-tripping revenue, recognition games, or anything that requires forensic evidence. You can have a dangerous feedback loop in a system where every invoice is real and every auditor is satisfied. What we are studying here is economic circularity: supplier support increases customers’ ability to spend, which increases supplier sales and cash, which increases supplier support again. A loop made out of ordinary incentives and financing constraints.

- NVIDIA, $N$, sells chips that power AI models.

- Partners, $P$, like OpenAI buy those chips, build models, and grow.

- NVIDIA reinvests a sliver of its revenue-say 3%-back into these partners.

Now we can try to understand this physics of small reinvestment from the first principles: build the simplest toy that has the behavior we’re arguing about, check the units, and see what the toy must do.

A machine you can hold in your head

Forget revenue for a moment. Revenue is a flow. It resets every period. Treating revenue like a stock that accumulates forever is how you accidentally build a perpetual motion machine and then congratulate yourself on discovering exponential growth.

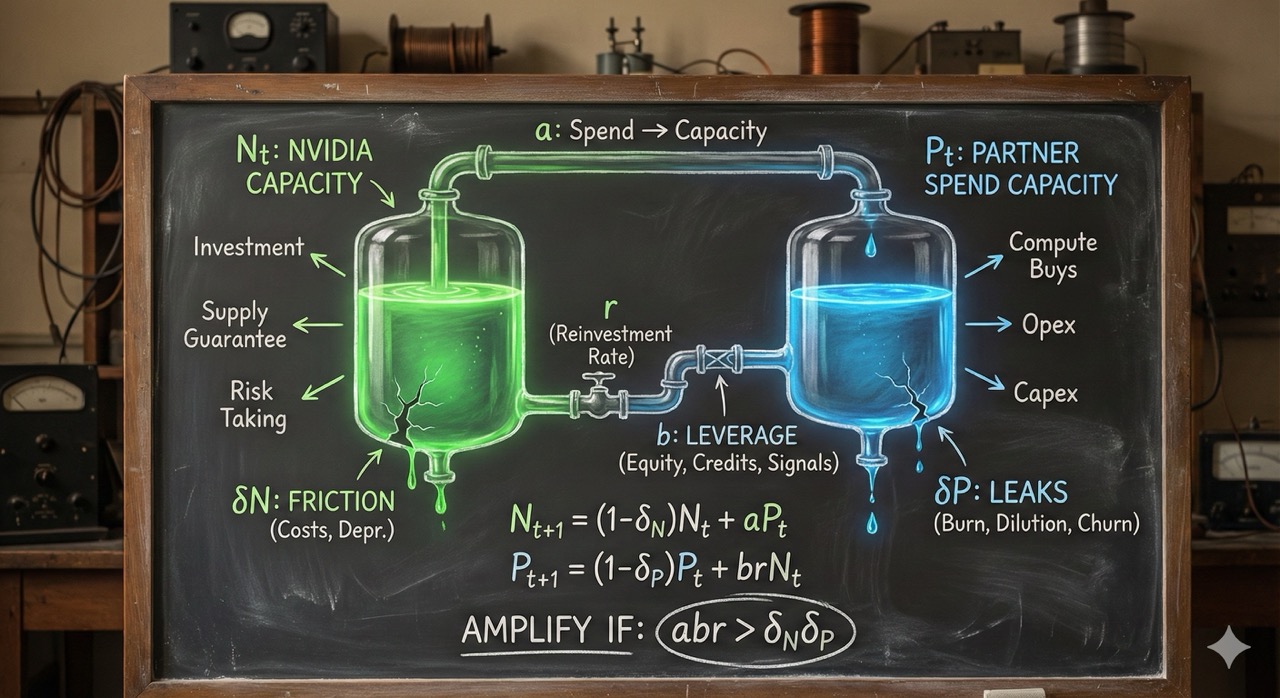

Instead, track something that behaves like a physical state: a reservoir.

Call one reservoir $N_t$: Nvidia’s deployable capacity at time $t$. Not just cash in the bank, but the practical ability to push the ecosystem-invest, extend terms, subsidize, guarantee supply, finance customers, take risk.

Call the other reservoir $P_t$: the partners’ spend capacity at time $t$. The ability to buy compute-capex budgets, opex runway, debt capacity, willingness of capital markets to fund the burn.

Now connect them with two couplings.

When partners have spend capacity, they buy compute. Some fraction of that spending turns into supplier capacity: revenue becomes margin, margin becomes free cash flow, cash becomes “we can do more.”

And when the supplier has capacity, it can recycle a small fraction back into partners: equity checks, credits, discounts, vendor financing, pre-buys, anything that makes partners more able to spend next period.

Finally, add leaks. Real reservoirs leak. In markets, leaks are costs, competition, depreciation, failures, dilution, churn, price pressure, and plain bad luck.

At that point you already see the shape: a loop with friction. A loop can be a flywheel or a scream. The difference is whether the loop multiplies disturbances faster than friction can eat them.

The smallest equations that don’t cheat

Write the dynamics in discrete time (quarters are a natural mental tick, but the time unit doesn’t matter as long as you’re consistent):

\[\begin{aligned} N_{t+1} &= (1-\delta_N)N_t + a,P_t \\ P_{t+1} &= (1-\delta_P)P_t + brN_t \end{aligned}\]This looks innocent, but it forces you to be honest about what each symbol means.

$\delta_N$ and $\delta_P$ are damping. They turn organized capacity into heat. In a boom they look small. In a tightening they jump. That jump matters later.

$r$ is the reinvestment rate, the number Jensen calls “low single digits.”

$a$ is how effectively partner spend capacity turns into supplier capacity. It hides the boring but crucial stuff: how concentrated spending is, how much of the partners’ compute budget routes to this supplier, and what margins survive competition.

$b$ is the part people wave away too quickly. In a sleepy world, $b$ is “the ROI of helping your customer.” In a reflexive world, $b$ is also a financing term. A supplier’s support can change a partner’s ability to raise money, sign leases, borrow, or be treated as credible. Not because anyone is lying, but because beliefs move constraints. A small check can change the terms on a much larger pool of external capital, and some of that capital becomes compute spend.

That’s the whole mechanism in one sentence: small recycling can matter if it changes the slope of someone else’s funding constraint.

Now the math asks its blunt question: does this coupled system damp out or amplify?

The one number the system actually cares about

Package the equations into a matrix:

\[\begin{bmatrix} N_{t+1} \\ P_{t+1} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1-\delta_N & a \\ br & 1-\delta_P \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} N_t \\ P_t \end{bmatrix}\]A physicist looks at that and immediately wants the dominant eigenvalue, $\lambda_{\max}$. Not because eigenvalues are fashionable, but because they tell you whether a small disturbance grows each cycle or shrinks each cycle.

In the roughly symmetric case where $\delta_N \approx \delta_P = \delta$, you get a clean expression:

\[\lambda_{\max} = (1-\delta) + \sqrt{abr}\]Now Jensen’s “how could 3% matter?” gets answered without drama.

If $\lambda_{\max} < 1$, shocks shrink. The loop is damped. Recycling is just a cost of doing business.

If $\lambda_{\max} > 1$, shocks grow. The loop amplifies. Even an honest system can start feeding on its own feedback.

The tipping condition is:

\[(1-\delta) + \sqrt{abr} > 1 \quad\Longleftrightarrow\quad \sqrt{abr} > \delta \quad\Longleftrightarrow\quad abr > \delta^2\]That last inequality, $abr > \delta^2$, is the whole point, because it kills “reasoning by size” at the root.

If you have $\delta_N \ne \delta_P$, this condition becomes $abr > \delta_N\delta_P$

The system does not care about $r$ alone. It cares about the product $a b r$ compared to the square of the damping.

You can keep $r$ in the low single digits and still cross the threshold if $a$ and $b$ are large enough, or if $\delta$ looks small in the regime you’re in. And regimes change.

This is not exotic. It’s the same logic behind microphones, reactors, and bridge oscillations. You don’t argue about whether one electron is “small.” You ask whether the loop gain beats the loss.

Where systemic risk actually comes from

If you stop here, it’s tempting to say “aha, bubble.” But that word is too blunt. The interesting physics is not “growth.” The interesting physics is fragility near a critical point.

When $\lambda_{\max}$ sits near 1, the system becomes touchy in a specific way. The memory of disturbances gets long. Shocks don’t get forgotten quickly. A useful back-of-the-envelope scaling for linear systems is that sensitivity behaves like:

\[\text{sensitivity} \propto \frac{1}{|1-\lambda_{\max}|}\]Don’t worship the constant. Look at the shape. Geometry. As $\lambda_{\max}$ approaches 1, the denominator gets small, and the system becomes sensitive faster than your intuition expects.

That is how “systemic” shows up in honest systems: not as a mysterious evil, but as correlation. Everyone starts moving together because the coupling is doing the coordinating. When the loop is strong, diversification starts to fail.

And notice what can move $\lambda_{\max}$ quickly: $b$ and $\delta$. Financing conditions, sentiment, rates, and refinancing windows can change the effective damping and the effective multiplier on a timescale much shorter than factory build-outs or product cycles. The parameters are not fixed knobs; they are regime-dependent.

So you can be in a world where the loop quietly amplifies, and then a regime shift flips the same loop into a contraction engine.

Why cascades need a cliff

So far, the system is linear and polite. Real cascades are not polite. They happen when someone hits a constraint.

Partners don’t smoothly “spend 7% less.” They hit a runway wall, fail a covenant, miss a refinance, lose access to a funding window, get capped by power availability, or get blocked by a regulator. The moment a constraint binds, the equations change.

You don’t need a complicated nonlinearity to capture this. You only need a cliff.

Say there is a minimum spend capacity $P_{\min}$ below which financing dries up and the partner can’t keep spending at the old rate. Then:

\[P_{t+1} = \begin{cases} (1-\delta_P)P_t + brN_t, & \mathrm{if}\; P_t \ge P_{\min},\\ (1-\delta_P)P_t, & \mathrm{if}\; P_t < P_{\min}. \end{cases}\]Now a cascade becomes easy to imagine.

A shock hits $N_t$. The recycled term $brN_t$ shrinks. $P_t$ drifts downward. If it crosses $P_{\min}$, the pump turns off. Then $P_t$ falls faster, which cuts $aP_t$, which shrinks $N_t$ further, which shrinks reinvestment further.

This means that partners can spend normally until they hit a financing threshold. Above $𝑃_{min}$, they can keep spending and keep receiving support; below it, funding dries up and the “extra inflow” shuts off, so spend capacity decays on its own—turning a mild shock into a regime change.

The flywheel becomes a spiral because the regime changed. Nothing dishonest happened. The loop simply ran backward across a threshold.

That’s what “cascading” means in the technical sense: the dynamics switch.

From two reservoirs to a system

The two-node model is a microscope, not a map. The real AI build-out is a network of many partners, many financing channels, and many shared dependencies. But the math lesson doesn’t change. It becomes a matrix story instead of a 2×2 story.

Replace the toy coupling with a weighted interdependence matrix $W$. Then “does it spread?” becomes the question “is the spectral radius less than one?”

\[\rho(W) < 1 \quad \text{means disturbances die out}\] \[\rho(W) > 1 \quad \text{means disturbances propagate}\]If you’ve seen epidemic models, this is the same role played by $R_0$. Below 1, outbreaks fizzle. Above 1, they spread. “Systemic” is just “the graph carries the shock.”

In networks, the thing that looks like diversification can quietly turn into coupling: common lenders, common hyperscalers, common data-center developers, common demand narratives, common refinancing windows. That’s how you get many nodes that appear independent in calm weather, and then move together in a storm.

The clean reply to Jensen

Jensen’s instinct is understandable: 1–5% sounds small. But in a feedback system, the size of the input is not the headline.

The headline is whether the loop gain beats the damping, and whether the system is operating near a critical boundary where small parameter shifts have large consequences.

A low reinvestment rate can matter if partner spending is concentrated enough ($a$ high), if supplier support changes financing constraints enough ($b$ high), and if the effective damping is low in the regime you’re in ($\delta$ small). In that world, “small” does not stay small. It becomes the trigger.

The microphone squeal is the right metaphor because it teaches the right habit.

Don’t stare at the leak.

Measure the gain around the loop.