Special thank yous to @ThogardPvP & @jacobeth4 from @0xFastLane, @ballsyalchemist from @sorella_labs, and @DariusTabai from @vertex_protocol for reading early versions of this article and providing feedback.

Introduction

As blockchain technology matures, decentralized applications (dApps) face increasing challenges in managing transaction sequencing to optimize user experience, value retention, and security. Traditional blockchain architectures often leave dApps at the mercy of external actors—such as miners, validators, searcher-builders —who control transaction ordering and inclusion. This lack of control can lead to value leakage, unfair user outcomes, including vulnerabilities to malicious behaviors like front-running or sandwich attacks.

Application-Specific Sequencing (ASS) emerges as a pivotal innovation, granting dApps greater control over the inclusion and ordering of transactions affecting their state, without the overhead and loss of asset composability of having to build and maintain their own appchains. By customizing sequencing mechanisms to their specific needs, dApps can mitigate negative externalities, internalize value, and enhance overall system efficiency. However, implementing ASS does come with complex trade-offs, particularly between composability and value capture, and raises critical questions about infrastructure design and incentive structures.

This article explores the nuances of ASS, synthesizing insights from current projects, and examines the inherent trade-offs in this design space. Our goal is to provide a comprehensive view for researchers and developers to further investigate and optimize ASS mechanisms.

Before we get deep into the application specific sequencing, let us briefly understand the fundamental concepts around sequencing and the vast design spectrum of sequencing, decentralized sequencing and shared sequencing.

Background - Sequencing Spectrum

Motivation - Importance of Transaction Sequencing

In blockchain networks, transaction sequencing—the process of determining which transactions are included in a block and in what order—is fundamental to the operation of dAapps. The sequence directly impacts:

- Value ownership and flow: The sequencer (generic) plays an important role in how assets are transferred and who gains control over them.

- User experience: Affects transaction confirmation times, fees, and predictability.

- Transaction integrity and fairness: Influences vulnerability to MEV extraction and manipulative practices.

The Role of MEV in Transaction Sequencing

MEV refers to the profit miners or validators or other extractors can make by reordering, including, or excluding transactions within the blocks they produce. MEV can manifest in various forms:

- Arbitrage MEV: Exploiting price differences across exchanges.

- Liquidation MEV: Profiting from liquidating undercollateralized positions.

- Sandwich MEV: Placing transactions before and after a target transaction to manipulate prices.

- Time-Bandit MEV: Reorganizing past blocks to extract additional value.

MEV extraction often comes at the expense of users and LPs of passive AMMs (or users who are providing liquidity at stale prices), leading to value leakage from the dApp ecosystem and undermining user trust.

What is Sequencing in Rollups?

Sequencing refers to the process of ordering transactions before they are executed and committed to the blockchain. In rollups, a sequencer is responsible for:

- Ordering transactions: Determining the sequence in which transactions are processed.

- Batching transactions: Grouping multiple transactions into batches to be posted to the main chain (Layer 1).

- Improving performance: Enhancing throughput and reducing latency by efficiently managing transaction flow.

Centralized Sequencing

- Definition: A single entity or a tightly controlled group manages the sequencing process.

- Advantages:

- High performance: Reduced coordination overhead leads to consensus overhead.

- Simplicity: Easier to implement and maintain.

- Special preferences: Can enforce sequencer operator’s preference of transaction ordering that can prevent MEV extraction (FCFS).

- Disadvantages:

- Censorship risks: A central sequencer can censor or reorder transactions unfairly.

- Liveness issues: If the sequencer fails or becomes malicious, the entire system can halt.

- Trust concerns: Users must trust the sequencer’s integrity and reliability.

Decentralized Sequencing

- Definition: Multiple independent entities participate in sequencing through a consensus mechanism.

- Advantages:

- Censorship resistance: Harder for any single entity to censor transactions.

- Improved liveness: The system remains operational even if some sequencers fail.

- Enhanced security: Distributed control reduces the risk of attacks.

- Disadvantages:

- Increased complexity: More complex to implement due to coordination among sequencers.

- Potential performance trade-offs: Consensus mechanisms can introduce latency.

- Economic incentive challenges: Aligning incentives among participants can be difficult.

- Centralization risks: Execution Tickets and Execution Auctions mechanisms used in decentralized sequencing dramatically increase centralization in the market for block proposals, even without multi-block MEV concerns.

Shared Sequencing

- Definition: Shared sequencing involves multiple rollups or chains utilizing a common set of sequencers. Instead of each rollup having its own sequencers, they share sequencing infrastructure. They share a decentralized network of sequencers.

- Advantages:

- Resource efficiency: Reduces duplication of infrastructure across rollups.

- Facilitated interoperability: Easier cross-rollup communication and composability.

- Enhanced security: Shared security model across participating rollups.

- Disadvantages:

- Coordination complexity: Managing sequencing across diverse rollups with different requirements.

- Incentive misalignment: Different rollups may have conflicting economic incentives.

- Risk propagation: Issues in one rollup could affect others sharing the sequencers (noisy neighbor problem).

Based Sequencing

- Definition: In Based Sequencing, L2 rollup transactions are sequenced by the L1 blockchain’s validators or proposers. L1 validators handle both L1 block proposals and L2 transaction sequencing.

- Advantages:

- Leverage L1 security: Uses L1’s existing security and decentralization for the rollup.

- Censorship resistance: Sequencing is distributed across L1 validators, reducing censorship risk.

- Liveness: Inherits L1 liveness, ensuring consistent transaction processing.

- Security: Benefits from the economic security of L1 validators.

- Atomic composability: Enables cross-layer composability between L1 and L2.

- Disadvantages:

- Incentive misalignment: Revenue from fees and MEV flows to L1, not the rollup.

- Reduced decentralization: Only a subset of validators may opt into sequencing, weakening decentralization.

- Complexity: L1 validators must run additional software, increasing operational overhead.

- Risks:

- Incentive conflicts: Validators may prioritize L1 revenue over optimal L2 sequencing.

- Security vulnerabilities: A smaller validator subset increases the risk of collusion or attacks.

Sequencing Mechanisms Today

Transaction sequencing decides the order in which blockchain transactions are processed. Different methods aim to improve performance, fairness, and security. The main mechanisms used today are:

- Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS) with Relays

- What it is: PBS separates the roles of block proposers (validators) and block builders. Builders create blocks that maximize profit via harvesting MEV, while relays securely pass these blocks to proposers.

- How it works: Proposers auction off the block rights through relays. Builders assemble blocks, relays deliver them securely, and proposers choose the most valuable block to add to the blockchain.

- Pros: Optimized block construction, higher validator revenue.

- Cons: Risk of builder/relay centralization and trust in relays, added complexity.

- Sequencers with Priority Fees or First-Come-First-Served (FCFS)

- What it is: In Layer 2s and appchains, sequencers order transactions by priority fee or arrival time (FCFS).

- How it works: Sequencers collect transactions; high-fee transactions are processed first or in the order in which they arrive to the sequencer

- Pros: Better performance, simpler design, FCFS changes MEV to latency games

- Cons: Centralized sequencers can manipulate transaction ordering, leading to MEV exploitation.

- Application-Specific Sequencing (ASS)

- What it is: dApps control how their own transactions are ordered to reduce MEV risks and improve user experience.

- How it works: dApps set rules for transaction order, preventing manipulative tactics like front-running.

- Pros: Better security, user experience, control over MEV, and retains composability as compared to being on your own app chain.

- Cons: Less interoperability, added complexity, possible centralization.

Incentives and Challenges for Dapps

Desire for isolated fee markets

One of the primary incentives for Dapps is the control over their own fee markets. Applications often prefer isolated fee markets to:

- Prevent congestion spillover: Avoid being affected by unrelated spikes in network activity that could increase transaction fees for their users.

- Maintain predictable costs: Ensure that transaction fees remain stable and predictable and aligned with the value provided by the application.

In a shared sequencing environment, fee markets can become merged. This merging means that high demand in one application can lead to increased fees across all applications sharing the sequencer. For example, if a popular game on a shared chain experiences a surge in activity, it could inadvertently raise transaction costs for a DEX operating on the same chain.

Capturing execution revenue and MEV

Dapps are increasingly interested in capturing a portion of the execution revenue and MEV generated by their platforms. In the context of rollups, Dapps are looking for two main things:

- MEV leakage: Without control over sequencing, external entities can extract MEV, reducing the revenue potential for the dApp itself.

- Desire for revenue sharing: Dapps seek mechanisms to receive a share of the fees and MEV generated by their users’ transactions or their user’s interactions with the applications.

Shared sequencing complicates this revenue capture because:

- Fee redistribution is complex: Distributing fees and MEV back to individual applications in a fair and enforceable manner is challenging.

- Incentive misalignment: Sequencers in a shared environment may prioritize their own revenue over the interests of specific Dapps or users.

Application-Specific Sequencing as an Alternative

To address these challenges, some applications are exploring application-specific sequencing. This model involves:

- Dedicated sequencers: The application runs its own sequencer or has greater control over the sequencing process.

- Custom fee structures: Ability to implement custom fee mechanisms that align with the application’s economic model.

- Direct revenue capture: Enhanced capability to retain fees and MEV within the application.

- Custom ordering logic: A transaction ordering solution using decentralized oracle networks (DON) to mitigate the detrimental effects of MEV, like Themis.

By controlling sequencing, Dapps can:

- Mitigate MEV risks: Reduce unwanted MEV extraction by external parties.

- Optimize user experience: Provide more predictable and stable transaction fees to users.

- Align incentives: Ensure that sequencer behavior is directly aligned with the application’s goals.

- Offer protection from external congestion: The application is insulated from network congestion caused by unrelated activities on other platforms.

By customizing the sequencing infrastructure, applications can achieve:

- Higher throughput: Optimize for the specific transaction patterns and volumes of the application.

- Lower latency: Reduce delays by fine-tuning the sequencing process to the application’s needs.

- Specialized features: Implement custom functionalities, such as local fee markets, MEV redistribution, advanced cryptographic techniques or state access optimizations.

Application-Specific Sequencing Frameworks

Fastlane’ ASS Framework

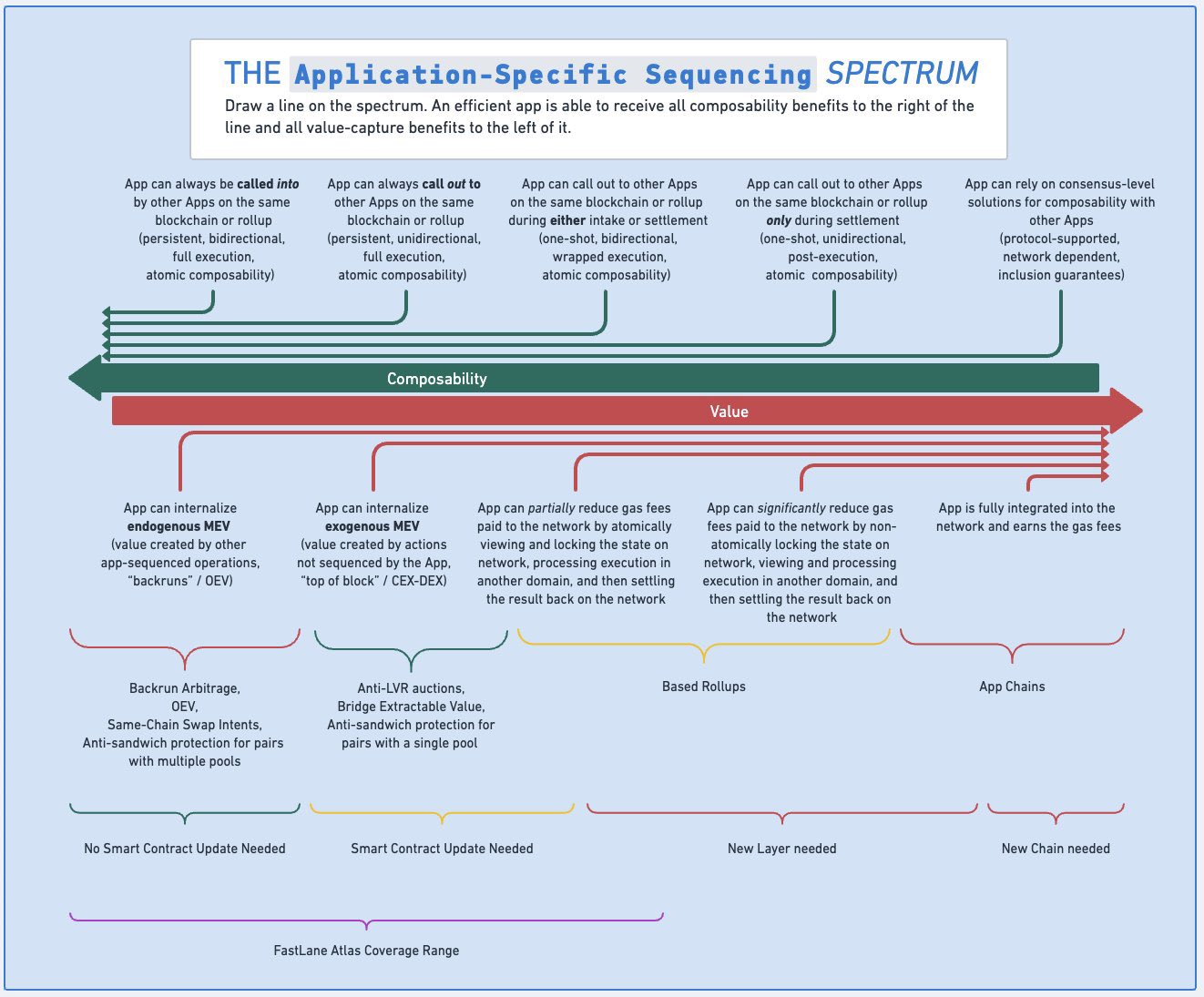

Figure: Fastlane’s ASS framework, source: Fastlane

Figure: Fastlane’s ASS framework, source: Fastlane

FastLane’s ASS Spectrum framework illustrates the balance between composability and value capture, showing how different sequencing approaches impact an application’s ability to interact with others and internalize value.

- High Composability vs. Value Capture: dApps that prioritize seamless interactions with other applications (high composability) may sacrifice some control over transaction sequencing, making them more susceptible to MEV attacks and less able to capture value internally.

- Low Composability vs. Value Capture: dApps that limit interactions with others gain more control over transaction ordering, allowing them to better protect against MEV exploitation and capture more value. However, this can reduce interoperability and potentially affect user experience.

- This tradeoff exists because the transaction ordering is determined within a separate mempool. The ASS orderer and bundler do not have knowledge of other transactions nor their state and therefore cannot provide atomic composability guarantees.

- Finding the Right Balance: Each dApp must consider its priorities and choose a sequencing approach that balances the need for composability with the desire to internalize value and protect users. This involves strategic decisions about how much to interact with other applications and how to structure transaction processing to optimize security and functionality.

Examples

- Highly Composable dApp: A lending platform that integrates with multiple other dApps to offer a wide range of services, accepting that it cannot fully control transaction sequencing but provides a rich user experience.

- Low Composability dApp: A decentralized exchange that focuses on securing transactions within its own platform, preventing MEV attacks by controlling transaction ordering, but offering limited interoperability with other applications.

Specific Use Cases Illustrating the Spectrum

Backrun Arbitrage and OEV

- Oracle Extractable Value (OEV) refers to the value that dApps can capture by controlling the sequencing of transactions that rely on external data from oracles. By managing the order in which these transactions are processed, dApps like API3 or Warlock can optimize the use of oracle-provided information, preventing external actors from manipulating transaction outcomes to extract value.

- The value captured through OEV is redistributed to various stakeholders within the ecosystem, including: dApp, users, and LPs.

- Mathematical Formulation**

Expected value from backrun arbitrage:

\[E[V_{\text{backrun}}] = \sum_{i} P_{i} \cdot \Delta_{\text{price}, i} \cdot V_{\text{trade}, i}\]where:

- $P_{i}$: Probability of a profitable backrun opportunity.

- $\Delta_{\text{price}, i}$: Price impact of transaction $i$.

- $V_{\text{trade}, i}$: Volume of the trade.

Rollup-Based Solutions

- Leveraging layer 2 solutions or app-specific chains optimizes performance and reduces costs. DApps gain extensive control over sequencing and execution parameters but may face challenges with isolation, security considerations, and bootstrapping liquidity, middleware integrations.

- Mathematical Considerations**

Cost reduction:

\[C_{\text{total}} = C_{\text{rollup}} + C_{\text{settlement}}\]where $C_{\text{rollup}}$ is significantly less than $C_{\text{on-chain}}$ execution costs.

Security model requires ensuring:

\[P_{\text{security breach}} \ll \epsilon\]where $\epsilon$ is an acceptably low probability threshold.

Anti-LVR Auctions

- LVR Explained: LPs suffer losses when arbitrageurs exploit stale prices in AMMs. LVR quantifies this loss compared to an optimally rebalanced portfolio.

-

Objective: Implement mechanisms to mitigate LVR, protecting LPs from value extraction.

-

Implementation

- Auction mechanism: dApps conduct auctions to determine transaction ordering that minimizes LVR.

-

Smart Contract updates: Modifications are required to support auction logic and enforce sequencing rules.

-

Mathematical Formulation

Minimizing LVR:

where $L_{\text{LVR}}$ is the loss due to LVR, and $\sigma$ represents the sequencing strategy.

\[\Delta P = P_{\text{external}} - P_{\text{AMM}}\] \[Q_{\text{arb}} = f(\Delta P)\]Where $f$ is a function representing how arbitrage volume responds to price discrepancies.

\[L_{\text{LVR}} = Q_{\text{arb}} \cdot \Delta P\]By batching, $\Delta P$ is reduced as the AMM’s price is updated less frequently, and the clearing price better reflects $P_{\text{external}}$.

Strategic Considerations for dApp Developers

When evaluating where to position your applications on the ASS spectrum, developers must consider:

Application Goals

- User experience: Is seamless integration with other dApps essential for your users?

- Revenue objectives: How critical is internalizing MEV to your business model?

- Security priorities: Do you need heightened control over transaction sequencing to mitigate risks?

Technical Constraints

- Infrastructure availability: Are the necessary tools and platforms available to implement your desired sequencing strategy?

- Development resources: Do you have the expertise and capacity to build and maintain more complex sequencing mechanisms?

Ecosystem Dynamics

- Market expectations: How will your positioning affect user adoption and trust?

- Competitive landscape: Are other dApps offering similar features with different sequencing approaches?

Regulatory and Compliance Factors

- Transparency requirements: Off-chain execution and reduced composability may impact compliance obligations.

- Risk management: Consider potential vulnerabilities introduced by non-standard sequencing methods.

Application-Specific Sequencing - Current Landscape

Fastlane’s Atlas Protocol

FastLane’s Atlas Protocol is a generalized execution abstraction designed to facilitate programmable MEV mitigation at the application layer. Atlas simplifies the deployment of custom Order Flow Auctions (OFAs), enabling developers to implement application-specific sequencing with greater ease and flexibility. By leveraging Execution Abstraction (EA), a subset of Account Abstraction (AA), Atlas replaces the need for certain guarantees from block builders, setting the way for permissionless order flow and decentralized MEV mitigation strategies across any EVM chain.

The Motivation Behind Atlas

Existing OFAs present centralization risks such as solver dominance and opaque MEV supply chains,. Atlas aims to provide default MEV protection without requiring users to change their RPC settings, targeting unsophisticated users who need protection the most.

Atlas Architecture Overview

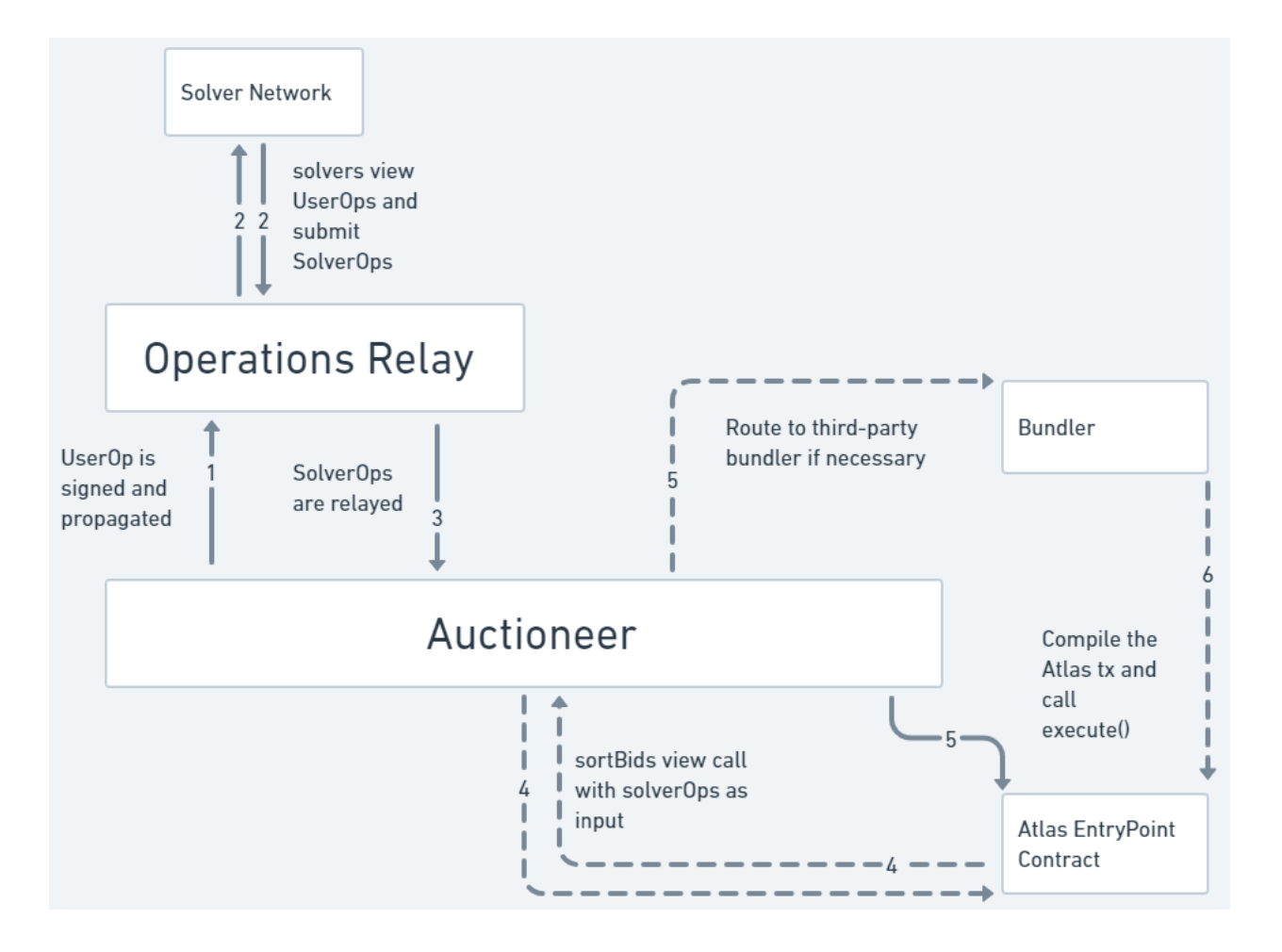

Figure: A high-level overview of the Atlas transaction lifecycle. Source: FastLane Atlas.

At its core, Atlas provides a modular and customizable framework that allows dApps to define their own transaction sequencing logic. The key components include:

- EntryPoint Contract: This smart contract orchestrates the entire transaction flow. It manages user and solver operations and ensures that the correct bundle bid is selected and executed, guaranteeing the proper sequence of actions.

- SDK: Simplifies integration with the protocol.

- Key Roles:

- Originator - Initiates the Atlas process by generating a UserOperation, a smart contract call or EIP-712 signed message representing the user’s intent.

- Auctioneer- Aggregates UserOperations with SolverOperations, sorts them using a bid valuation function defined in the DAppControl module, and ensures the correct execution order.

- Operations Relay - Facilitates communication between originators, auctioneers, and solvers. This can be a traditional relay, an L3, or even a smart contract on the same network as the application.

- Bundler - Packages the full Atlas transaction and submits it to the network for inclusion in a block.

- Solver - Competes to provide the best execution for a given UserOperation, potentially capturing MEV for the benefit of users or applications.

- Execution Environment: Secure operation execution using

delegateCallandPermit69. - atlETH: Wrapped ETH for value transfer and gas management.

- DAppControl Contracts: Define application-specific logic and parameters.

In FastLane’s Atlas protocol, the Bundler can be run by:

- Anyone (Permissionless): Any entity can act as a bundler, allowing for a decentralized system.

- Designated Entities: A smart contract (such as a batch aggregator), a trusted entity, or a group chosen by the application can bundle transactions.

- Self-Bundling: The originator (user) or solver can bundle and submit their own transactions.

- Secure Solutions: Advanced setups using secure environments (like TEEs) ensure bundlers can’t tamper with transactions.

The CallChainHash guarantees that bundlers can’t change the order of operations, keeping the process secure.

Key Roles in Atlas

Originator

- Role: Initiates the Atlas process by generating a

UserOperation, an EIP-712 signed message representing the user’s intent. - Flexibility: Can be an end-user, smart contract, or any entity capable of verification by the Atlas

EntryPointcontract. - Impact: Sets the parameters and initial conditions for the transaction, influencing downstream execution.

Auctioneer

- Role: Aggregates

UserOperationswithSolverOperations, sorts them using a bid valuation function defined in theDAppControlmodule, and ensures the correct execution order. - Assignment: Often the originator or a trusted entity designated by the application.

- Impact: Determines the priority of solver bids, directly affecting the transaction sequencing.

Operations Relay (OR)

- Role: Facilitates communication between originators, auctioneers, and solvers.

- Customization: Applications choose an OR based on their needs—prioritizing decentralization, latency, or privacy.

- Impact: Transmits operations efficiently while potentially mitigating frontrunning and censorship.

Bundler

- Role: Packages the full Atlas transaction and submits it to the network for inclusion in a block.

- Configurations:

- Permissionless: Any entity can act as a bundler.

- Designated: Specific, trusted entities or decentralized solutions handle bundling.

- Impact: Ensures transactions are included on-chain without altering the execution order, due to the

CallChainHashmechanism.

Solver

- Role: Competes to provide the best execution for a given

UserOperation, potentially capturing MEV for the benefit of users or applications. - Impact: Enhances execution quality and efficiency by finding optimal transaction paths or backrun opportunities.

Technical Mechanisms

Atlas EntryPoint Contract

The Atlas EntryPoint contract is the backbone of the protocol:

- Central coordination: Manages the execution flow of

UserOperationsandSolverOperations. - Execution Abstraction: Uses Account Abstraction to allow applications to define custom execution logic.

CallChainHashverification: Ensures the prescribed sequence of operations is preserved, preventing tampering by any intermediary.

CallChainHash

- Definition: A cryptographic hash representing the ordered sequence of operations in an Atlas transaction.

- Function: Guarantees the integrity and order of operations, making the transaction sequence immutable once signed.

- Generation: Created using the

getCallChainHash(SolverOperations[])function and signed by the auctioneer.

Execution Environment (EE)

- Purpose: Provides a secure, trust-minimized environment for executing operations via

delegateCall. - Permit69: A specialized token permittance function that enhances security by verifying token transfer origins, preventing unauthorized transfers.

- Impact: Ensures that application-specific logic is executed securely and as intended.

atlETH

- Definition: A wrapped ETH token used within Atlas.

- Functions:

- Gas fee escrow: Solvers pre-fund gas fees, ensuring they cover the cost of their operations.

- Value transfer: Facilitates secure and efficient value transfer within transactions.

- Cross-operation flash loans: Enables complex financial operations by allowing temporary borrowing of atlETH within a transaction.

Native Bundling

- Concept: Aggregating multiple operations into a single transaction, leveraging AA to simplify execution and gas fee management.

- Benefits:

- Permissionless execution: Removes dependency on block builders for transaction inclusion guarantees.

- Atomicity: Ensures all operations execute as a unit, maintaining the integrity of the transaction sequence.

- MEV mitigation: Allows applications to capture and redistribute MEV according to their own policies.

How Atlas Achieves Application-Specific Sequencing

Atlas empowers applications to control transaction sequencing through several mechanisms:

- Custom execution logic: Developers define execution parameters and sequencing rules in the

DAppControlmodule. - Immutable sequencing with allChainHash: The signed

CallChainHashlocks the sequence of operations, preventing any alterations. - Execution Abstraction: Users submit intents rather than full transaction paths, allowing applications to interpret and execute as per their logic.

- Solver competition: Solvers submit

SolverOperations, and applications decide their execution order based on custom bid valuation functions. - Native bundling and atomic execution: Operations are bundled and executed atomically, ensuring adherence to the application’s sequencing.

- Cross-chain compatibility: Atlas does not rely on specific block builder guarantees, making it adaptable to any EVM-compatible chain.

Handling MEV and Backrun Auctions

- Intent-Centric auctions: Users submit intents, and solvers compete to fulfill them efficiently, capturing MEV for the benefit of users or applications.

- Backrun auctions: Solvers attach backruns to extract MEV or OEV, with value shared according to application policies.

- Batching auctions: Solvers compete to sequence a batch of UserOperations in the most measurably efficient manner, as defined by the DAppControl’s bid valuation function.

- “Top of Block” auctions: For DApps willing to reduce composability to internalize exogenous MEV (such as LVR), Solvers compete to be the first to interact with the application each block.

Handling Flashloans in Atlas Protocol

Atlas Protocol features an integrated, Atlas-native cross-operation flashloan system designed to enhance the flexibility and efficiency of decentralized financial operations. Within Atlas, smart contract hooks can initiate flashloans by invoking the borrow() function before the solver phase of the transaction lifecycle. This seamless integration allows originators to access liquidity without needing to hold gas tokens, facilitating transactions that interact with smart contracts dependent on the msg.value parameter.

Additionally, these flashloans serve as collateral to support and manage multi-stage settlements during the atomic creation and sale of structured products or derivatives between originators and solvers.

By embedding flashloan capabilities directly into the Atlas framework, the protocol enables complex financial strategies while ensuring secure and efficient transaction sequencing. This design not only streamlines capital utilization for users but also maintains the integrity and robustness of the DeFi ecosystem by preventing common flashloan exploits and ensuring fair value distribution among all stakeholders.

Security and Trust Minimization

- Immutable Sequencing: Atlas uses CallChainHash, a cryptographic hash, to ensure transaction orders remain unaltered, preventing intermediaries from tampering with the sequence.

- Secure Execution Environment: The EntryPoint Contract manages operations securely using delegateCall and Permit69, which verifies token transfers and blocks unauthorized access, safeguarding user assets.

- Solver accountability: Solvers must escrow funds in atlETH to cover gas fees, promoting honest behavior and discouraging spam or malicious actions since they bear the cost of failed transactions.

- Decentralized solver competition: A market of solvers competes to execute user operations, reducing reliance on any single entity and minimizing trust assumptions.

- MEV mitigation: By controlling transaction sequencing at the application layer, Atlas mitigates MEV risks like front-running and sandwich attacks, protecting users from value extraction by external actors.

- Atomic Execution: Atlas enables atomic execution of operations, ensuring that either all operations succeed or none do, maintaining consistency and security.

- Transparency: Open-source code allows community auditing and verification, enhancing transparency and reducing the need for users to trust the system blindly.

- Customizable Security: Developers can define custom execution logic and security settings through DAppControl modules, tailoring security features to their application’s specific needs.

Integration Steps for Applications

Integrating Atlas into an application involves three steps:

- Embed the Atlas SDK: Developers incorporate the SDK into their application to interact with the protocol.

- Create and Publish a DAppControl Module: Define the custom logic, permissions, sequencing rules, and parameters for transaction processing.

- Initialize the DAppControl Contract: Link the application’s DAppControl module to the Atlas EntryPoint contract and configure the necessary settings.

Sorella Labs’ Angstrom

Sorella Labs introduces Angstrom, a fully permissionless hook that implements application-specific sequencing. Currently on Uniswap V4, they are integrated with decentralized ASS.

The LP Dilemma

LPs provide liquidity to DEXs, enabling users to trade assets. However, they often face:

- Adverse selection: LPs are unaware of real-time CEX prices and provide quotes that may be stale, making them vulnerable to arbitrage.

- LVR losses: LPs incur losses when arbitrageurs exploit price discrepancies between the DEX and CEX.

The Attribution Problem in MEV

The attribution problem refers to the difficulty in identifying the specific parties affected by MEV extraction and ensuring they are appropriately compensated. Current blockchain architectures lack the granularity to:

- Trace MEV sources: Pinpoint which users or LPs are adversely affected.

- Redistribute value fairly: Allocate MEV profits back to those who incurred losses.

Addressing MEV Problems

Angstrom uses competitive the top of bundle auctions, LVR auctions, batch auction mechanisms, and integrates searchers to create a market for LVR. This allows LPs to recover losses from adverse selection, swappers to receive optimal execution, and searchers to access arbitrage opportunities.

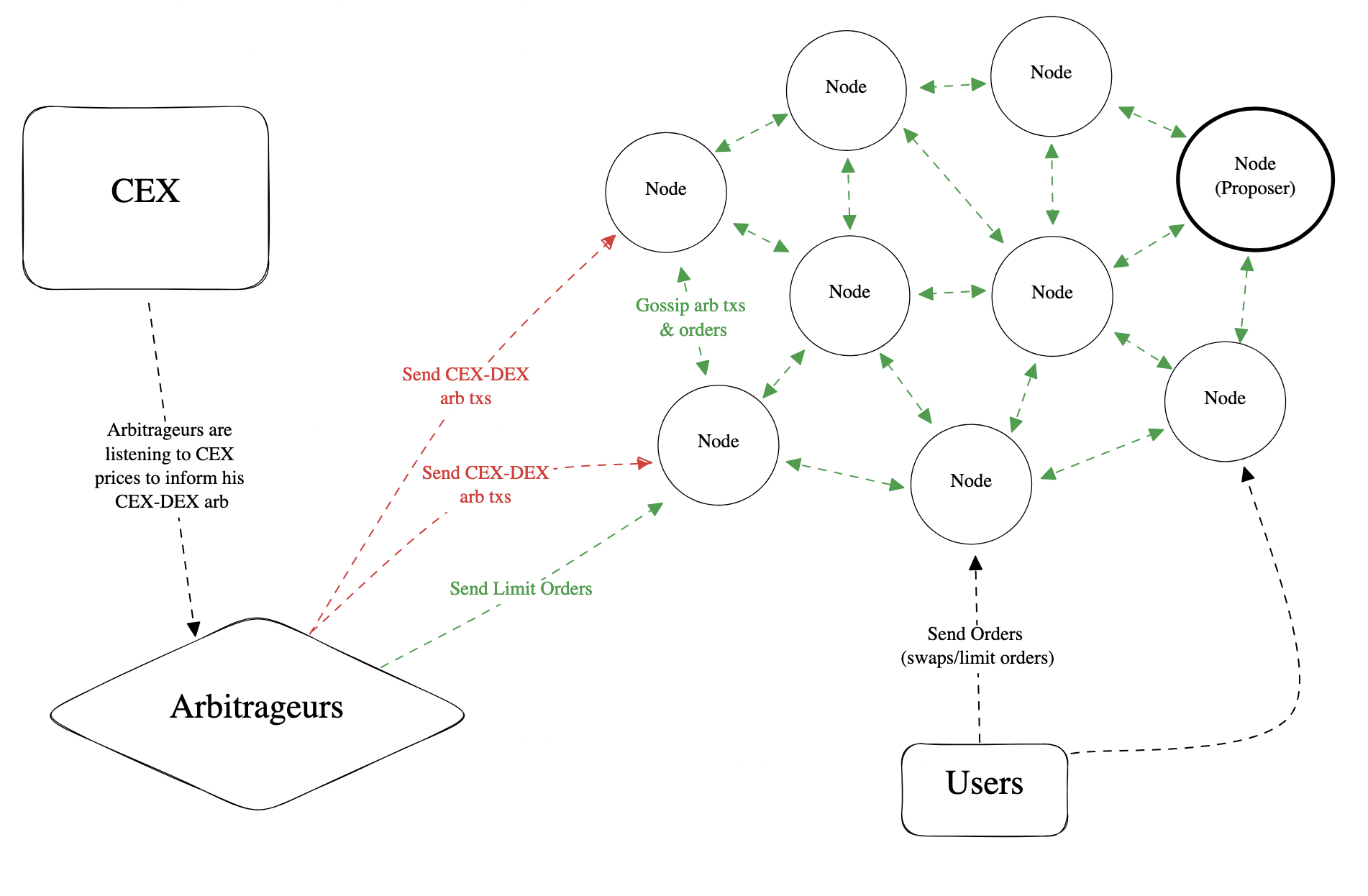

Figure: Angstrom Network Topology, Source: Fastlane

Figure: Angstrom Network Topology, Source: Fastlane

How Angstrom Works

- Stakeholders:

- Liquidity Providers (LPs): Provide liquidity and are compensated for LVR losses.

- Swappers: Execute trades with guaranteed execution and MEV protection.

- Searchers: Arbitrageurs who bid in LVR auctions, contributing to LP compensation.

- Angstrom nodes: Construct optimal bundles and earn protocol fees.

- LVR auction mechanism: Ensures competitive bidding and directs value back to LPs.

- Settlement timeline: From order submission to trade settlement, ensuring deterministic and fair execution.

- Bundle exclusivity: Atomic bundles executed in a specific order, preventing value leakage and reducing censorship incentives.

Technical Details

- Ensuring arbitrage opportunities: Angstrom’s construction ensures arbitrage exists whenever there’s a price delta between the DEX and CEX.

- Limit orders and uniform clearing price: Transient limit orders are executed at a single clearing price, minimizing slippage and preventing market order attacks.

- Angstrom Network Architecture:

- Nodes: Gossip, cache, verify orders, and construct optimal bundles.

- Bundle Lifecycle: Includes gossip, pre-proposal, and submit phases.

- Incentives: Competition among searchers drives value to LPs; nodes earn rewards and can be slashed for dishonest actions.

Benefits and Impact

- Democratizing arbitrage: Reduces the influence of high-frequency traders and promotes a competitive landscape.

- Neutralizing proposer timing games: Eliminates timing advantages and simplifies consensus.

- Stakeholder Benefits:

- LPs: Recover losses and are incentivized to provide liquidity.

- Swappers: Receive fair prices with MEV protection.

- Searchers: Access profit opportunities without excessive bribes.

- Nodes: Earn rewards and contribute to decentralization.

Security and Trust Minimization

Sorella’s Angstrom enhances security and minimizes trust requirements through application-specific sequencing, directly addressing vulnerabilities associated with MEV.

-

Eliminating MEV exploitation: Batch auctions with uniform clearing prices prevent front-running and sandwich attacks by settling trades at a single price. Transient one-block limit orders further reduce MEV extraction by minimizing exploitation windows.

-

Trust minimization through decentralization: Permissionless participation allows anyone to run a node or act as a searcher, enhancing decentralization and reducing reliance on central authorities. Node operators re-staked and staked native tokens, aligning their incentives with network security; dishonest behavior results in slashed stakes, discouraging malicious actions.

-

Censorship resistance: Atomic bundle execution reduces incentives for miners or validators to censor transactions by executing them in a predetermined order. Decentralized order relay eliminates centralized intermediaries, reducing the risk of censorship or manipulation. The decentralized order relay is achieved through a network of node operators who participate in peer-to-peer broadcasting of orders, collective verification, and consensus on transaction inclusion. By requiring over ⅔ of the network’s signatures and preventing any single node from controlling the order flow, Angstrom enhances censorship resistance and reduces the risk of manipulation.

-

Protection against market manipulation: Limit orders and uniform clearing prices prevent attackers from manipulating prices through large orders, ensuring fair execution for all participants. Arbitrage profits from searchers are redirected to compensate liquidity providers for adverse selection losses.

-

Secure and transparent auctions: Competitive, permissionless auctions promote fair market dynamics and reduce collusion risks. MEV is accurately attributed and redistributed to affected parties, enhancing fairness and trust.

-

Economic incentives aligned with security: Rewards for node operators incentivize honest participation and contribute to network security. Searchers profit without excessive bribes, encouraging compliance with protocol rules. Users and liquidity providers receive fair compensation and MEV protection, fostering trust and engagement.

-

Resilience against attacks: Staking requirements deter Sybil attacks by increasing the cost of creating multiple identities. Fault tolerance ensures network functionality even if some nodes fail or act maliciously. Efficient order handling mitigates denial-of-service attacks by reducing the effectiveness of attempts to overwhelm the network.

-

Minimizing trust assumptions: Transparency through open-source protocols and auditable processes allows participants to verify security properties independently, reducing reliance on trust. Internalizing MEV opportunities reduces dependence on external systems, minimizing potential vulnerabilities.

Vertex Protocol

Vertex is a perp and spot DEX. It employs application-specific sequencing through an off-chain sequencer to optimize performance and minimize MEV risks.

Key Features

- Hybrid liquidity model: Combines a central limit order book (CLOB) with an integrated AMM, enhancing liquidity utilization.

- Application-Specific Sequencing: Off-chain sequencer achieves order-matching latency comparable to top-tier centralized exchanges.

- Universal cross-margining: Allows users to manage multiple positions from a single account, enhancing capital efficiency.

- Vertex Edge: Extends liquidity across multiple chains, addressing liquidity fragmentation.

Addressing Challenges

Vertex addresses DeFi challenges by:

- High performance: Off-chain sequencer enables real-time trading experiences essential for high-frequency traders and better price discovery

- MEV mitigation: Minimizes exposure to front-running and sandwich attacks by handling operations off-chain.

- Capital efficiency: Cross-margining reduces collateral requirements and supports complex trading strategies.

- Liquidity aggregation: Vertex Edge unifies liquidity pools across chains, reducing slippage and market impact.

Capturing Value for Users

Users benefit from:

- Performance improvements: Reduced slippage and improved execution quality.

- Cost savings: Lower gas fees and minimized MEV exposure enhance net LP returns.

- Access to liquidity: Aggregated liquidity provides deeper markets.

- Flexibility: Integrated services streamline the user experience.

Security and Trust Minimization

-

Mitigating MEV exploitation: By processing orders off-chain with an off-chain sequencer, Vertex reduces exposure to MEV attacks like front-running and sandwich attacks, since transactions aren’t publicly broadcast before execution. Low-latency execution (5–15 milliseconds) further minimizes the window for potential attackers to exploit transaction information.

-

Trust minimization: The sequencer regularly commits batches of transactions to the blockchain, ensuring transparency and allowing users to verify that off-chain operations align with on-chain records. Through a non-custodial design, users retain control of their assets, eliminating the need to trust centralized intermediaries.

-

Protection against manipulation: Transparent order books provide users with real-time market data, reducing the potential for price manipulation. Secure state synchronization ensures the sequencer maintains accurate alignment with the on-chain state, preventing inconsistencies that could be exploited.

-

Economic incentives aligned with security: Incentive structures align participants’ interests toward maintaining a secure and fair trading environment. Risk management protocols—including real-time monitoring and automatic margin checks—protect the system from excessive risk and potential defaults.

-

Resilience against attacks: Sharded state management enhances scalability and reduces the attack surface in cross-chain operations. Advanced synchronization techniques such as off-chain parallel processing of orders, atomic cross-chain transactions, efficient cross-chain communication protocols and more frequent state consistency checks may mitigate latency and prevent timing-based attacks during cross-chain transactions.

-

Minimizing trust assumptions: Open-source code allows users to audit and verify the protocol’s security, reducing the need for blind trust.

Security Considerations

While Vertex Protocol offers impressive performance and innovative features, its reliance on an off-chain sequencer introduces certain security concerns:

-

Sequencer misbehavior: The off-chain sequencer handles order matching, which could potentially allow it to engage in unfair practices like front-running or trading against users. This is akin to MEV exploits, where privileged entities profit at the expense of regular users.

-

Censorship risks: Since the sequencer controls which transactions are processed, there’s a possibility it could censor specific users or transactions, undermining the platform’s neutrality and censorship resistance.

-

Fairness in order matching: Without full transparency into the sequencer’s operations, users may question whether orders are matched fairly and in the correct sequence. Ensuring that the matching process is transparent and verifiable is essential for maintaining trust.

Alignment with Base Layers

Vertex aligns incentives with underlying networks by settling trades on users’ origin chains, increasing network activity and benefiting validators. Vertex Edge fosters collaborative growth among connected networks.

Semantic Layer

Semantic Layer enables dApps to implement Verifiable Sequencing Rules (VSR) and Verifiable Aggregation Rules (VAR), giving them control over transaction sequencing and execution. This allows dApps to:

- Observe transactions: View user transactions before execution.

- Enforce execution policies: Implement custom rules and real-time circuit breakers.

- Autonomously execute functions: Reduce reliance on external triggers.

By empowering dApps with sequencing sovereignty, Semantic Layer mitigates MEV leakage and opens possibilities for innovative designs, such as AI-powered applications and execution layer independence.

Conclusion

Application-Specific Sequencing represents a significant advancement, allowing dApps to balance composability and value capture according to their needs. By granting control over transaction sequencing and execution, ASS enables dApps to mitigate MEV risks, optimize operations, and innovate.

Projects like FastLane’s Atlas Protocol, Sorella Labs’ Angstrom, Vertex Protocol, and Semantic Layer showcase diverse approaches to implementing ASS. Each addresses unique challenges and offers solutions tailored to their objectives, contributing to a richer and more resilient decentralized ecosystem.

Application-Specific Sequencing will play a crucial role in empowering dApps to achieve greater sovereignty, efficiency, and fairness, driving broader adoption and innovation in decentralized applications.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fw5Qu400ySY

- https://x.com/ThogardPvP/status/1829331564029005924

- https://github.com/FastLane-Labs/atlas/tree/main

- https://github.com/FastLane-Labs/atlas_whitepaper/blob/main/Atlas_Whitepaper.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lLR_6tnKL2I

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tHpAazIFDtQ

- https://x.com/0x94305/status/1580169706413051904

- https://chain.link/education-hub/maximal-extractable-value-mev

- https://research.chain.link/whitepaper-v2.pdf

- https://blog.chain.link/chainlink-fair-sequencing-services-enabling-a-provably-fair-defi-ecosystem/

- https://docs.vertexprotocol.com/getting-started/vertex-edge

- https://eprint.iacr.org/2021/1465

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6jWf8zuBg2g

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MaoZmrsH0iA

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iV1XhAA8AZo

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G2Cbh9z1ags

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9uTXfD9kYJw

- https://ethereum-magicians.org/t/eip-7727-evm-transaction-bundles/20322

- Centralization in Attester-Proposer Separation, https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.03116