WIP - WORK IN PROGRESS

Introduction

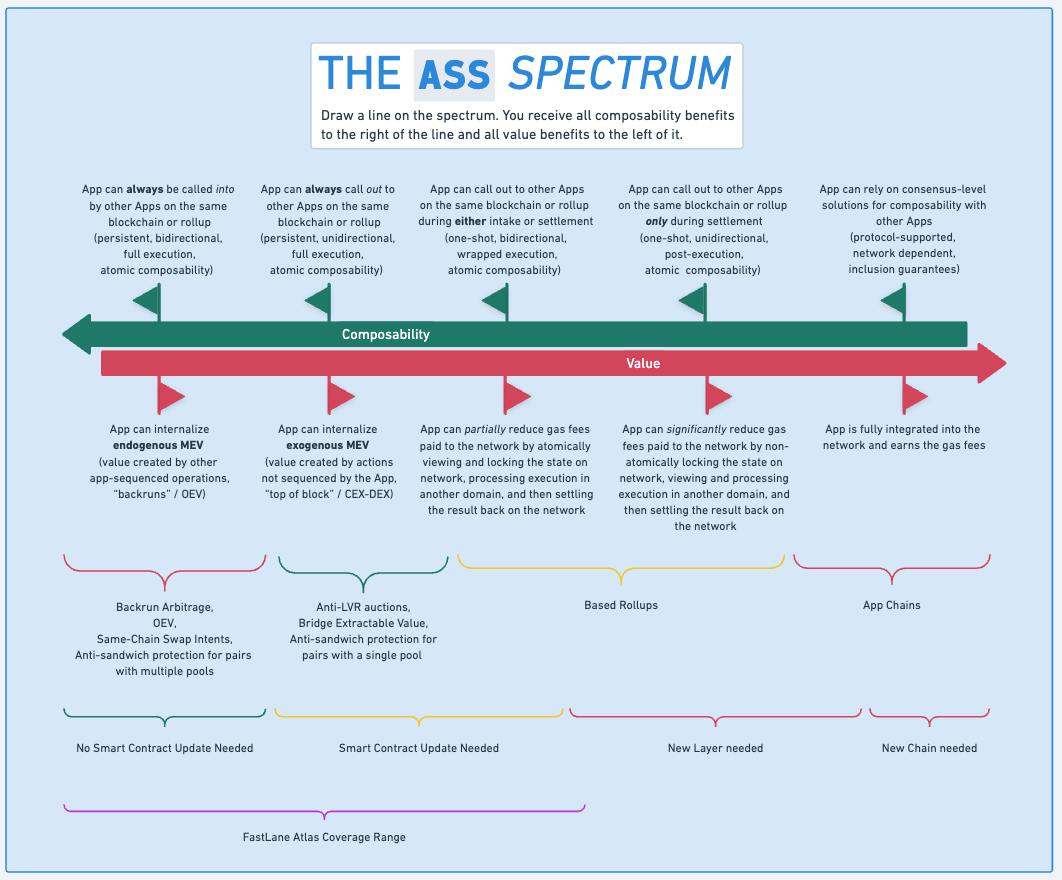

In this technical blog, we will explore deeper into the gas efficiency trade-off, using the insights from Fastlane’s ASS framework1. Their observations, particularly around domain-specific constraints, will serve as the foundation for developing a rigorous, mathematical model that captures the intricacies of gas efficiency in different blockchain domains (e.g., Solana, Ethereum, Monad, etc.). We will extend the linear trade-offs into a multi-dimensional space, using formal mathematical notation and visualizing the trade-off with a 2D graph.

Understanding the trade-offs between critical factors such as composability, MEV capture, and gas efficiency is key to optimizing blockchain architectures. Fastlane’s ASS framework provides an initial approach to visualizing these trade-offs. However, the simplified model often overlooks domain-specific factors, particularly regarding gas efficiency, where different blockchain systems impose unique constraints and opportunities.

Figure: Fastlane’s ASS framework, source: Fastlane1

Figure: Fastlane’s ASS framework, source: Fastlane1

Overview - The Gas Efficiency Trade-Off in Blockchain Architectures

In any blockchain system, gas efficiency reflects the cost of computational resources required to execute transactions. Optimizing gas efficiency is crucial for scalability, user experience, and long-term viability. However, improving gas efficiency often comes with trade-offs—particularly in MEV (Maximum Extractable Value) capture and composability.

The ASS framework provides a simplified view yet very useful, suggesting a linear trade-off between gas efficiency and value extraction. But, as Alex Watts, CEO & Founder of Fastlane, points out1, domain-specific constraints play a significant role in shaping these trade-offs. Systems like Solana, with its access lists that enable granular state-locking, allow for higher gas efficiency without sacrificing too much composability or MEV capture. Conversely, other blockchains like Monad lack such mechanisms, leading to a steeper decline in gas efficiency when optimizing for composability or value extraction.

Our goal in this article is to formalize this trade-off with mathematical model, defining how gas efficiency depends on composability, MEV capture, and other variables in a domain-specific way. Let’s build a strong foundation with key variable definitions and domain-specific functions.

Definitions and Notations

- $C$: Composability—the ability of decentralized applications (dApps) to interact seamlessly. $C \in [0, 1]$, where 0 represents no composability and 1 represents full atomic composability.

- $M$: MEV Capture—the extent to which a system captures endogenous and exogenous MEV. $M \in [0, 1]$, where 0 represents no MEV capture and 1 represents full MEV capture.

- $G_d$: Gas Efficiency—the efficiency of gas usage in a specific domain $d$. $G_d \in [0, 1]$, where 1 represents the maximum gas efficiency.

- $S$: Security—the system’s ability to resist attacks such as front-running or re-entrancy. $S \in [0, 1]$, where 1 represents full security.

- $L$: Latency—the time taken for transaction finality. Lower values represent faster finality.

Domain-Specific Gas Efficiency Function

Since gas efficiency varies across different blockchains, we define it as a domain-specific function $G_d$, where $d$ represents the blockchain (e.g., Solana, Monad, Ethereum, etc.):

\[G_d = f_d(C, M, S, L)\]The function $f_d$ depends on the specific characteristics of the blockchain in question. For example, Solana’s access lists allow for better optimization of gas usage, while Monad lacks such features, resulting in different trade-offs.

Let’s take a closer look at how this gas efficiency function works for each domain.

Solana

In Solana, granular control over state locking via access lists allows for better gas efficiency without requiring state access or execution during the validation process. We can model gas efficiency for Solana as:

\[G_{\text{Solana}} = C^\alpha \cdot M^\beta \cdot S^\gamma \cdot L^\delta \quad \text{where } \alpha, \beta, \gamma, \delta > 0\]In this case:

- $\alpha$: Composability’s effect on gas efficiency. Solana can handle composability better, allowing for high gas efficiency even when $C$ is large.

- $\beta$: Represents the trade-off between MEV capture and gas efficiency. Solana’s architecture mitigates this trade-off better than most blockchains.

- $\gamma$ and $\delta$: The effect of security and latency on gas efficiency. These parameters depend on how sensitive the system is to transaction finality and security requirements.

Monad

For Monad, lacking such optimizations, the gas efficiency trade-off is more sensitive to changes in MEV capture and composability. We introduce a penalty term to account for Monad’s limitations in handling MEV:

\[G_{\text{Monad}} = C^\alpha \cdot M^\beta \cdot S^\gamma \cdot L^\delta \cdot h(M)\]Here, $h(M)$ is a penalty function that grows with MEV capture, reflecting the higher cost in gas efficiency as the system tries to capture more MEV. This term penalizes the system for lack of composability optimizations and reflects a steeper trade-off curve.