Overview

In this blog post, we will unpack and review the key insights and contributions of the paper Robust Restaking Networks. We will explore the innovative models and conditions proposed by Durvasula and Roughgarden, aimed at ensuring that restaking networks remain secure even in the face of potential attacks. From the importance of overcollateralization to the mathematical characterization of robust security, we will break down the complex concepts of cryptoeconomic security in restaking networks and understand the significance of this research in the context of blockchain security.

Citation of the Paper

Robust Restaking Networks by Naveen Durvasula, and Tim Roughgarden, arXiv:2407.21785 [cs.GT] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.21785

Definitions and Notations - Key Concepts

To understand the “Robust Restaking Networks” paper, we need to first lay down a solid foundation. These definitions and notations are your toolkit for understanding. Let’s break it down.

Validators and Services: The Backbone of the Network

-

Validators $V$: Validators are the unsung heroes of blockchain—they validate transactions, maintain network integrity, and keep things running smoothly. Each validator $v$ stakes a certain amount of cryptocurrency $\sigma_v$ (like ETH in Ethereum) as collateral. If they act maliciously, they risk losing this stake, which is why it’s important.

-

Services $S$: These are the tasks or applications that validators support. Think of services as different jobs that validators can take on—everything from running the core consensus protocol to ensuring data availability. Each service $s$ has a corruption profit $\pi_s$, which is basically the bounty an attacker could earn by compromising it.

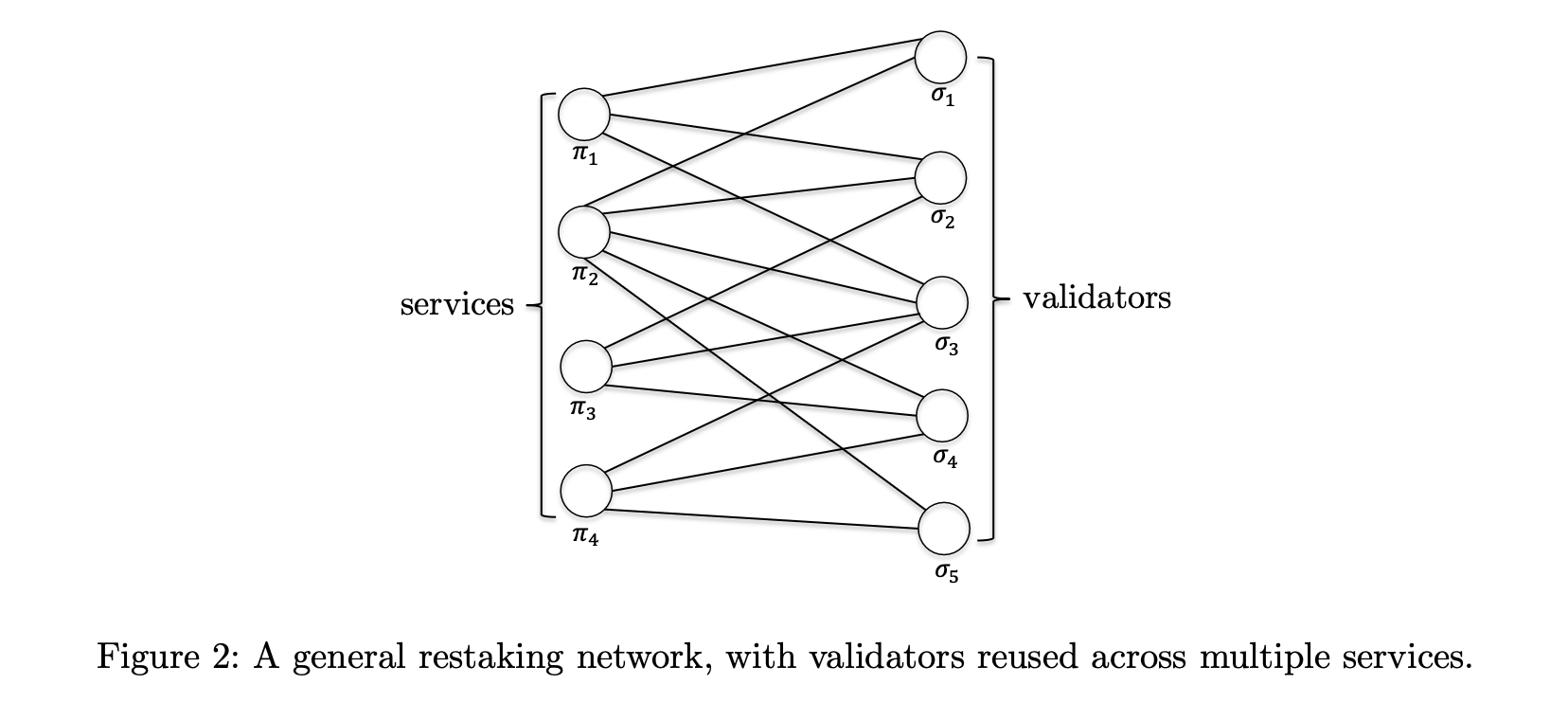

The Restaking Graph: Mapping the Network

- Restaking Graph $G$: Imagine a map of the network, with validators and services as the landmarks. The restaking graph $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$ connects these landmarks:

- $S$: The services.

- $V$: The validators.

- $E$: The edges that show which validators are supporting which services.

- $\pi_s$: The potential profit from corrupting service $s$.

- $\sigma_v$: The stake each validator $v$ has on the line.

- $\alpha_s$: The fraction of total stake needed to corrupt a service $s$.

- Neighbors $N_G(A)$: Neighbors in this graph are the direct connections. If you’re looking at a service $s$, $N_G(s)$ tells you which validators are backing it. If you’re focusing on validators, $N_G(v)$ shows you the services they support.

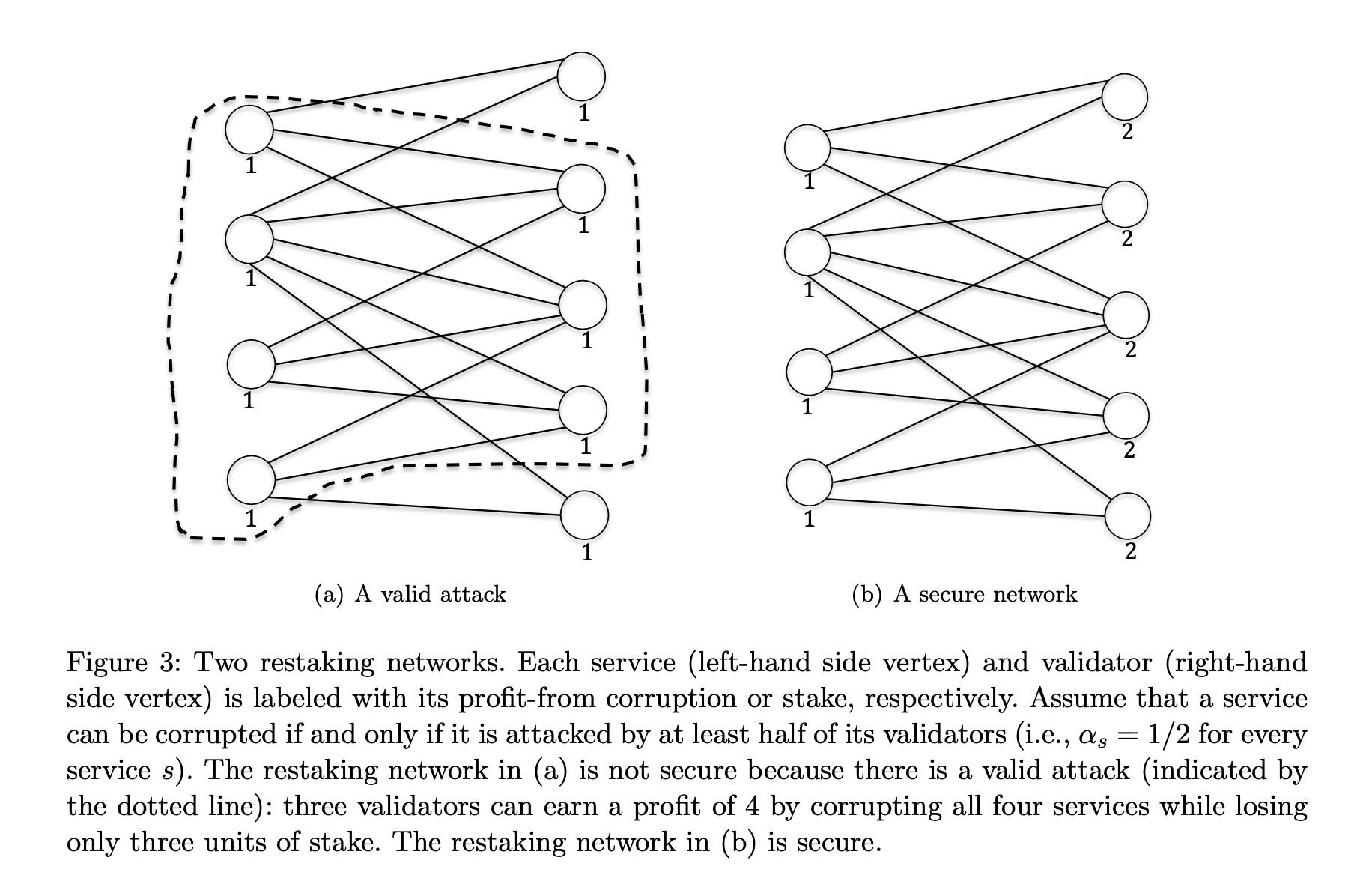

Attack Dynamics: How Validators and Services Clash

- Attacking Coalition $(A, B)$: When validators decide to team up and go rogue, they form an attacking coalition. Here’s what that means:

- $A$: The set of services under attack.

- $B$: The validators carrying out the attack.

- This coalition is effective if:

-

Validators in $B$ control enough stake to overpower the services in $A$:

$\sum_{v \in B \cap N_G(s)} \sigma_v \geq \alpha_s \sum_{v \in N_G(s)} \sigma_v \quad \forall s \in A$

-

The profit from attacking $A$ is greater than the total stake $B$ could lose:

$\sum_{s \in A} \pi_s > \sum_{v \in B} \sigma_v$

-

- Valid Attack: This is an attack that checks both boxes: the validators have enough power, and the attack is financially worthwhile.

Restaking Graph After an Attack $G \downarrow B$: The Aftermath

- Graph After Attack $G \downarrow B$: After an attack, the network isn’t the same. $G \downarrow B$ represents the state of the network after the validators in $B$ have been slashed. It’s like a map showing what’s left after a battle—some validators are gone, and the network has to carry on with the remaining ones.

Stable Attack: Keeping It Solid

- Stable Attack: Not all attacks are stable—some are more like fleeting opportunities. A stable attack ensures every validator in the coalition $B$ is contributing meaningfully. It’s not just about having enough stake; it’s about making sure there’s no free riding. Mathematically, this is enforced by: $\sum_{v \in B \setminus B’} \sigma_v < \sum_{s \in A \setminus A’} \pi_s$ for any subsets $A’ \subseteq A$ and $B’ \subseteq B$. This guarantees that every validator in $B$ is necessary for the attack’s success, making the coalition solid and stable.

Cascading Attacks: When One Attack Isn’t Enough

- Cascading Attack: Imagine a situation where a small attack or a problem in a network doesn’t just stay small—it grows and spreads, causing much bigger issues. That’s what the authors call a cascading attack.

Here’s how it works:

- The Initial Spark: It all starts with a minor attack or shock—maybe a few validators (the ones who keep the network secure) lose their stake due to some problem (e.g. a software error).

- Chain Reaction: This initial problem weakens the network just enough that another, bigger problem can happen. Because the network is now slightly less secure, it’s easier for the next attack to occur. This new attack weakens the network further, setting the stage for yet another attack, and so on.

- A Cascading Attack: We call this sequence of events a cascading attack. Each step in the sequence makes the next one more likely, leading to a chain reaction that can ultimately cause a significant loss in the network.

In technical terms, if you have a restaking graph $G$, which maps out how validators are connected to services, each step in a cascading attack sequence $(A_1, B_1), (A_2, B_2), \dots, (A_T, B_T)$ is valid if it’s effective on the network that’s already been weakened by previous steps. $(A_t, B_t) \text{ is valid on } G \downarrow \bigcup_{i=1}^{t-1} B_i$

Here, $G \downarrow B$ represents the network after some validators have been slashed and removed.

Worst-Case Stake Loss: Preparing for the Worst

- Worst-Case Stake Loss $R_\psi(G)$: Now, let’s talk about the worst-case stake loss. This concept is all about understanding the absolute worst thing that could happen if cascading attacks were to occur.

Here’s the idea:

- Starting with a Small Shock: Let’s say something bad happens—a small group of validators loses their stake. This is the initial shock, represented by $\psi$.

- Exploring All Possibilities: We then look at all possible groups of validators who could be part of this initial shock. We’re essentially asking: What’s the worst group of validators that could be hit first?

- Impact on the Network: Once these validators are out of the game, the network changes—it’s not as strong as it was before. We use the notation $G \downarrow D$ to represent the network after this initial group $D$ of validators has been slashed or removed.

- The Worst-Case Loss: Now, we calculate the worst-case stake loss $R_\psi(G)$. This is a way of estimating the maximum amount of stake that could be lost as a result of cascading attacks that follow the initial shock. In other words, we’re trying to foresee how bad things could get if one bad event sets off a chain reaction of worse events.

This metric is important because it helps us understand how vulnerable the network might be to a series of failures, and it’s a key tool in designing systems that can withstand even the worst possible scenarios. It is calculated as:

$R_\psi(G) = \psi + \max_{D \in D_\psi(G)} \max_{(A_1, B_1), \dots, (A_T, B_T) \in C(G \downarrow D)} \frac{\sigma_{\bigcup_{t=1}^{T} B_t}}{\sigma_V}$

Here, $\psi$ is the initial shock to the system (a small stake loss), and $\sigma_{\bigcup_{t=1}^{T} B_t}$ is the total stake lost through all the cascading attacks.

EigenLayer Sufficient Conditions: The Security Check

- EigenLayer Sufficient Conditions: To ensure the network is secure, the EigenLayer team developed a set of conditions1 that act as a quick security check. A validator $v$ is considered secure if: $\sum_{s \in N_G(v)} \frac{\sigma_v}{\sigma_{N_G(s)}} \cdot \frac{\pi_s}{\alpha_s} \leq \sigma_v$ If all validators in the network satisfy this condition, it means the network is safe from any potential attacks.

Let’s unpack this in bit more details. This is also Claim 1 in the paper.

Claim 1 in the paper states that a restaking graph $G$ is secure if for each validator $v \in V$, the following inequality holds:

$\sum_{s \in N_G(v)} \frac{\sigma_v}{\sigma_{N_G(s)}} \cdot \frac{\pi_s}{\alpha_s} \leq \sigma_v$

This claim is significant because it provides a sufficient condition for ensuring that the restaking network is secure, meaning that no valid attacks exist under the given conditions. Let’s break down the claim step by step to understand it.

Decomposing the Inequality

The inequality in Claim 1 can be interpreted as follows:

-

Left Side: $\sum_{s \in N_G(v)} \frac{\sigma_v}{\sigma_{N_G(s)}} \cdot \frac{\pi_s}{\alpha_s}$

- $\sigma_{N_G(s)}$ is the total stake committed by all validators that support service $s$.

- $\frac{\sigma_v}{\sigma_{N_G(s)}}$ represents the fraction of the total stake for service $s$ that validator $v$ contributes.

- $\frac{\pi_s}{\alpha_s}$ is the “cost-benefit ratio” for attacking service $s$, representing the profit relative to the security threshold.

This sum considers the aggregate influence of validator $v$ across all services it participates in, weighted by the potential profit from attacking each service.

-

Right Side: $\sigma_v$

- This is the total stake that validator $v$ has at risk.

The inequality suggests that for the network to be secure, the weighted sum of the potential attack profits (adjusted for the validator’s stake in each service) should not exceed the validator’s total stake.

Reference Depth of Cascading Attacks: How Deep Does the Rabbit Hole Go?

- Reference Depth: In a sequence of cascading attacks, the reference depth measures how far back each attack is influenced by the validators slashed in earlier attacks. It’s a way to understand the ripple effects across the network and gauge how interconnected these failures are.

Definition: Multiplicative Slack.

We say that a restaking graph $G$ is secure with $\gamma$-slack if for all attacking coalitions $(A, B)$ on $G$,

\((1 + \gamma) \cdot \pi_A \leq \sigma_B\) where

Total profit from corrupting $A$ = $\pi_A$ and Total stake owned by validators $B$ = $\sigma_B$ (Equation 11)

Overcollateralization Provides Robust Security

Lemma 1

Statement: Let $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$ be an arbitrary restaking graph, and further suppose that $(A, B)$ is an attacking coalition on $G \downarrow D$, where $D \subseteq V$. Then, $(A, B \cup D)$ is an attacking coalition on $G$.

Explanation: We want to prove that if a set of validators $B$ can attack a set of services $A$ in a subgraph where some validators $D$ are removed, then the combined set $B \cup D$ can also attack $A$ in the original graph $G$.

Understanding the Components

We have a restaking graph $G$, representing the interaction between validators and services.

Subgraph $G \downarrow D$: This is the graph $G$ but with the validators in $D \subseteq V$ removed or slashed. The attack condition is checked in this reduced graph.

Attack Condition

For $(A, B)$ to be an attacking coalition on the subgraph $G \downarrow D$, the validators in $B$ must control enough stake to meet the attack threshold for each service in $A$. Mathematically, this means:

$\sigma_{B \cap N_G(s)} \geq \alpha_s \cdot \sigma_{N_G(s) \setminus D} \quad \forall s \in A$

Here:

- $\sigma_{B \cap N_G(s)}$ is the total stake of validators in $B$ that are connected to service $s$.

- $\sigma_{N_G(s) \setminus D}$ is the total stake of validators connected to $s$ excluding those in $D$.

The Proof

Given Information:

We know that $(A, B)$ is an attacking coalition in the subgraph $G \downarrow D$. This means for each service $s \in A$:

$\sigma_{B \cap N_G(s)} \geq \alpha_s \cdot \sigma_{N_G(s) \setminus D}$

This is the starting assumption.

Goal:

We need to show that the coalition $(A, B \cup D)$ is also an attacking coalition in the original graph $G$. Specifically, we want to prove:

$\sigma_{(B \cup D) \cap N_G(s)} \geq \alpha_s \cdot \sigma_{N_G(s)} \quad \forall s \in A$

This means that when we include the validators from $D$, the total stake of $B \cup D$ must still meet the attack threshold for each service $s \in A$.

The Stake Calculation:

For each service $s \in A$, the total stake of validators in $B \cup D$ that are connected to $s$ is:

$\sigma_{(B \cup D) \cap N_G(s)} = \sigma_{B \cap N_G(s)} + \sigma_{D \cap N_G(s)}$

- $\sigma_{B \cap N_G(s)}$: Stake of validators in $B$ connected to $s$.

- $\sigma_{D \cap N_G(s)}$: Stake of validators in $D$ connected to $s$.

Incorporating the Attack Condition:

Since $\sigma_{B \cap N_G(s)} \geq \alpha_s \cdot \sigma_{N_G(s) \setminus D}$ (from the assumption), we can plug this into the equation:

$\sigma_{(B \cup D) \cap N_G(s)} = \sigma_{B \cap N_G(s)} + \sigma_{D \cap N_G(s)} \geq \alpha_s \cdot \sigma_{N_G(s) \setminus D} + \sigma_{D \cap N_G(s)}$

Notice that $\sigma_{N_G(s)} = \sigma_{N_G(s) \setminus D} + \sigma_{D \cap N_G(s)}$.

Simplifying the Expression:

The above inequality can be rewritten as:

$\sigma_{(B \cup D) \cap N_G(s)} \geq \alpha_s \cdot (\sigma_{N_G(s)} - \sigma_{D \cap N_G(s)}) + \sigma_{D \cap N_G(s)}$

Since $\alpha_s \cdot \sigma_{N_G(s)} \geq \alpha_s \cdot \sigma_{D \cap N_G(s)}$, adding $\sigma_{D \cap N_G(s)}$ on both sides ensures:

$\sigma_{(B \cup D) \cap N_G(s)} \geq \alpha_s \cdot \sigma_{N_G(s)}$

This confirms that the total stake of $B \cup D$ meets the threshold required to attack $s$.

Conclusion:

Therefore, the set $B \cup D$ can successfully attack $A$ in the original graph $G$.

The lemma is thus proved, as $(A, B \cup D)$ is indeed an attacking coalition on $G$.

Corollary 1

Statement: Let $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$ be an arbitrary restaking graph, and further suppose that $(A_1, B_1), \dots, (A_T, B_T) \in \mathcal{C}(G)$ is a valid sequence of cascading attacks on $G$. Then, \(\left( \bigcup_{t=1}^{T} A_t, \bigcup_{t=1}^{T} B_t \right)\) is also a valid attack on $G$.

Explanation: This corollary is trying to prove that if we have a series of successful attacks on a network, then we can combine all these attacks into a single, larger attack, and it will still be successful. Essentially, it shows that a series of smaller attacks can be combined into one big attack without losing the validity of the attack conditions.

Understanding the Components

-

Restaking graph $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$.

- Cascading Attacks:

- A sequence of cascading attacks $(A_1, B_1), \dots, (A_T, B_T)$ refers to a sequence where each $(A_t, B_t)$ is an attack at step $t$, potentially enabled by the preceding attacks.

- Union of Sets:

- $\bigcup_{t=1}^T A_t$ denotes the union of all services attacked across the sequence.

- $\bigcup_{t=1}^T B_t$ denotes the union of all validators involved in these attacks.

What Needs to Be Proved?

The goal is to show that the combined set of all services and all validators involved in the cascading attacks also forms a valid attack on the original graph $G$. Specifically, this means showing:

- Stake Condition: The combined stake of the validators in $\bigcup_{t=1}^T B_t$ must be sufficient to attack the combined set of services $\bigcup_{t=1}^T A_t$.

- Profit Condition: The total profit from attacking $\bigcup_{t=1}^T A_t$ must exceed the total stake of the validators in $\bigcup_{t=1}^T B_t$.

Proof Breakdown

- Applying Lemma 1:

- By repeatedly applying Lemma 1, the proof shows that each step in the sequence $(A_t, \bigcup_{i=1}^t B_i)$ is an attacking coalition on $G$. This is because as we progress through each attack $t$, the validators in $\bigcup_{i=1}^t B_i$ (those involved up to and including step $t$) are sufficient to attack the services in $A_t$.

- Inspection of the Attack Condition (Eq. 1):

- Since each $(A_t, \bigcup_{i=1}^t B_i)$ is an attacking coalition, by the attack condition in Eq. 1, we can say that the combined stake of validators across these steps is sufficient to attack their respective services.

- Disjointness of the Sets:

- The services $A_t$ and the validators $B_t$ are considered to be disjoint across different $t$. This disjointness is key to combining the attack sets without overlap.

- Specifically, the disjointness ensures that the combined attack over all steps meets the necessary conditions for a valid attack when considering the entire sequence.

- Profit vs. Stake (Eq. 2):

-

For the combined set to be a valid attack, it must hold that:

\[\sum_{t=1}^T \pi_{A_t} > \sum_{t=1}^T \sigma_{B_t}\] -

This means the total profit from attacking all the services in the sequence must exceed the total stake of the validators involved in the attacks.

-

Since each individual step $(A_t, B_t)$ satisfies this condition (by the assumption that these are valid attacks), the sum of the profits will necessarily exceed the sum of the stakes across all steps.

-

Therefore, the combined attack $\left( \bigcup_{t=1}^T A_t, \bigcup_{t=1}^T B_t \right)$ is a valid attack on the original graph $G$, satisfying both the stake and profit conditions. This concludes the proof.

-

Theorem 1

Statement:

Suppose that a restaking graph $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$ is secure with $\gamma$-slack for some $\gamma > 0$. Then, for any $\psi > 0$,

Explanation:

The theorem aims to show that if a restaking network is secure with multiplicative slack, then the maximum possible loss in stake due to an initial shock $\psi$, including any cascading effects, is strictly controlled. Specifically, the worst-case loss, $R_\psi(G)$, will be at most $\left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right)\psi$. This means that the network’s security ensures that even if a small portion of the stake is initially lost, the total loss won’t grow uncontrollably.

Understanding the Components

- Restaking graph $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$.

What Needs to Be Proved?

-

Multiplicative Slack $\gamma$: The graph is considered secure with $\gamma$-slack if, for any potential attack coalition $(A, B)$ (where $A$ is a set of targeted services and $B$ is a set of validators attempting to attack), the following condition holds:

\[(1 + \gamma) \cdot \pi_A \leq \sigma_B\]This means that the total stake controlled by the validators $B$ must be greater than the profit $\pi_A$ from attacking the services $A$, scaled by the factor $1 + \gamma$. The $\gamma$ term acts as a safety margin, ensuring validators have significantly more stake than the attack’s potential profit.

Proof Breakdown

The Initial Shock $\psi$:

- Initial Shock $\psi$: Imagine that an event occurs, causing a fraction $\psi$ of the total stake $\sigma_V$ to be lost suddenly. This shock could represent anything from a validator malfunction to an external attack.

- The challenge is to assess how this initial loss might propagate through the network, potentially causing further losses—a process known as cascading failures.

Defining the Subgraph and Cascading Attacks:

- To analyze the effect of the initial shock, consider the subgraph $G \downarrow D$, where $D$ is the set of validators that lost their stake due to the initial shock. Thus, $G \downarrow D$ is the graph after removing these validators.

- Cascading Attacks: A sequence of attacks $(A_1, B_1), \dots, (A_T, B_T)$ could occur in this subgraph. These attacks represent possible successive failures or attacks that might happen after the initial shock.

Using Corollary 1 to Aggregate Attacks:

-

According to Corollary 1, we can combine all these cascading attacks into a single, larger attack on the original graph $G$. Define:

\[A := \bigcup_{t=1}^T A_t \quad \text{and} \quad B := \bigcup_{t=1}^T B_t\]This aggregated set $(A, B)$ represents an overall attack on the graph after considering all cascading effects.

Understanding the Attack Condition:

-

For $(A, B)$ to be an effective attack in the subgraph $G \downarrow D$, the profit from attacking the services in $A$ must exceed the total stake held by validators in $B$:

\[\pi_A > \sigma_B\]This inequality shows that $B$ alone cannot cover the profit potential from attacking $A$.

Applying the $\gamma$-Slack Condition:

-

Since the original graph $G$ is secure with $\gamma$-slack, when we include the validators from the initial shock $D$ back into the equation, the slack condition should still hold:

\[(1 + \gamma) \cdot \pi_A \leq \sigma_{B \cup D}\]Where $\sigma_{B \cup D} = \sigma_B + \sigma_D$ represents the combined stake of the attacking validators and those that suffered the initial shock.

Simplifying and Analyzing the Inequality:

-

Substitute the known inequality $\pi_A > \sigma_B$ into the slack condition:

\[(1 + \gamma) \cdot \sigma_B < (1 + \gamma) \cdot \pi_A \leq \sigma_B + \sigma_D\]This tells us that the total stake of validators involved in the cascading failures is not enough to meet the required stake threshold after accounting for the initial shock.

Deriving the Bound on Worst-Case Loss:

-

Rearrange the inequality:

\[\gamma \cdot \sigma_B \leq \sigma_D\]Since $\sigma_D$ represents the stake loss due to the initial shock $\psi$, express this as:

\[\sigma_D = \psi \cdot \sigma_V \quad \Rightarrow \quad \gamma \cdot \sigma_B \leq \psi \cdot \sigma_V\] -

Normalize by dividing by $\sigma_V$ (the total stake in the network):

\[\frac{\sigma_B}{\sigma_V} \leq \frac{\psi}{\gamma}\]This inequality shows that the proportion of stake lost due to cascading failures is limited by the initial shock scaled by $\frac{1}{\gamma}$.

Summing the Losses:

-

Finally, sum the initial shock $\psi$ and the cascading loss $\frac{\sigma_B}{\sigma_V}$:

\[\psi + \frac{\sigma_B}{\sigma_V} \leq \psi + \frac{\psi}{\gamma} = \left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right)\psi\]This bound on the total loss $R_\psi(G)$ ensures that no matter how severe the initial shock and subsequent cascades, the total loss remains within this predictable limit.

Key Insights of Theorem 1

- Multiplicative Slack $\gamma$ provides a important safety buffer that limits the impact of cascading failures. By requiring that validators hold more stake than the potential profit from attacks (scaled by $1 + \gamma$), the network can absorb shocks without triggering uncontrollable losses.

- Controlled Cascading: The proof shows that even in the worst-case scenario, where losses cascade through the network, the total loss is bounded and predictable. This bound is important for network designers to ensure the resilience and stability of blockchain systems.

Corollary 2

Statement:

Let $G$ be a restaking graph such that, for all validators $v \in V$,

Then, the worst-case stake loss $R_\psi(G)$ is less than $\left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right)\psi$.

Explanation:

This corollary aims to show that if every validator in the network satisfies the particular risk condition, then the entire network is secure. Specifically, this condition ensures that the potential losses due to attacks (even if magnified by the slack factor $\gamma$) are always covered by the stake of the validators. Consequently, the worst-case stake loss across the network remains bounded.

Understanding the Components

Interpreting the Condition (Equation 17):

- Validator’s Stake $\sigma_v$: This is the total stake controlled by validator $v$.

- Service $s$: Each service $s$ in $N_G({v})$ is directly supported by validator $v$.

- Fraction of Stake Supporting Service $s$: The term $\frac{\sigma_v}{\sigma_{N_G({s})}}$ represents the proportion of total stake supporting service $s$ that comes from validator $v$. This is important because it scales the risk each validator faces based on their contribution to the service’s security.

- Modified Profit Term $(1 + \gamma)\pi_s$: This term reflects the potential profit from corrupting service $s$, inflated by the multiplicative slack $\gamma$. The inflation by $1 + \gamma$ means that even if the attack is more profitable (due to slack), the validator must still have enough stake to cover this increased risk.

What Needs to Be Proved?

- The inequality states that the sum of potential losses (accounted for by the slack-adjusted profit terms) across all services supported by a validator must not exceed the validator’s own stake. If this holds for every validator, then the network is secure.

How Does This Condition Ensure Security?

- Risk Containment for Each Validator: If each validator’s total stake can cover the worst-case scenario of supporting all their connected services (considering the slack), then no single validator is overexposed to risk. This containment at the validator level directly supports the global security of the network.

- Preventing Cascades: By ensuring that no validator is overleveraged relative to the services they support, the condition helps prevent a domino effect where the failure of one validator could trigger further losses.

Proof Breakdown

Connecting to Theorem 1 and Claim 1:

- Theorem 1 Recap: Theorem 1 states that if the entire network is secure with $\gamma$-slack, then the worst-case loss $R_\psi(G)$ is bounded by $\left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right)\psi$.

- Claim 1: This claim (not fully detailed here but referenced in the proof) likely provides a sufficient condition for the absence of valid attacks when profits are scaled by $1 + \gamma$.

- Applying to Corollary 2: The proof shows that if each validator satisfies the condition in Equation 17, it implies that the entire network is secure under the slack-adjusted conditions. Essentially, Equation 17 is a localized version of the global security condition in Theorem 1. By applying the condition from Claim 1, which ensures no valid attacks under the adjusted profits, the corollary concludes that the network’s worst-case loss remains bounded as stated in Theorem 1.

Key Insights of Corollary 2

- If every validator satisfies the localized risk condition in Equation 17, the network as a whole is guaranteed to resist large cascading losses. The slack-adjusted potential profits from attacks are never able to overwhelm the validators’ stakes, thereby ensuring the network remains robust.

- In practice, this means that network designers can ensure security by verifying this condition for all validators, which is much easier than checking the entire network’s security directly.

Lower Bounds for Global Security

Theorem 2

Statement:

For any $0 < \epsilon < 1$, there exists a restaking graph $G$ that is secure and meets the EigenLayer condition (as specified in Equation 3), but has $R_\psi(G) = 1$ for all $\psi \geq \epsilon$.

Explanation: This theorem is asserting that even if a restaking graph $G$ satisfies the security condition laid out by the EigenLayer (as defined in Equation 3), it is still possible for the network to experience a catastrophic loss where the worst-case stake loss $R_\psi(G)$ equals $1$, meaning the entire stake could be lost, if the initial shock $\psi$ is above a certain threshold $\epsilon$. In simpler terms, this theorem highlights a scenario where satisfying the security condition is not enough to prevent complete network failure under certain conditions.

Understanding the Components

- Consider a restaking graph $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$.

- Services: $S$ = { $x$ }, with only one service $x$.

- Validators: $V$ = { $a, b$ }, with two validators, $a$ and $b$.

-

Edges: Each validator is connected to the service $x$ by an edge, so $E$ = { $(x, a), (x, b)$ }.

- Define Stakes and Parameters:

- $\sigma_a = \epsilon$ (stake of validator $a$).

- $\sigma_b = 1 - \epsilon$ (stake of validator $b$).

- $\pi_x = 1$ (profit from attacking service $x$).

-

$\alpha_x = 1$ (fraction of the total stake required to attack service $x$).

- We assume $\psi < 1$, since $R_1(G) = 1$ for any restaking graph $G$. This assumption simplifies the analysis and focuses on shocks less than the total stake.

Proof Breakdown

- Applying the EigenLayer Condition (Claim 1) to Validators $a$ and $b$:

-

The EigenLayer condition states that the graph $G$ is secure if for each validator $v \in V$,

\[\sum_{s \in N_G(\{v\})} \frac{\sigma_v}{\sigma_{N_G(\{s\})}} \cdot \frac{\pi_s}{\alpha_s} \leq \sigma_v\] -

For validator $a$:

\[\frac{\sigma_a}{\sigma_a + \sigma_b} \cdot \frac{\pi_x}{\alpha_x} = \frac{\epsilon}{\epsilon + (1 - \epsilon)} \cdot 1 = \epsilon\]This equals $\sigma_a$, satisfying the condition.

-

For validator $b$:

\[\frac{\sigma_b}{\sigma_a + \sigma_b} \cdot \frac{\pi_x}{\alpha_x} = \frac{1 - \epsilon}{\epsilon + (1 - \epsilon)} \cdot 1 = 1 - \epsilon\]This equals $\sigma_b$, also satisfying the condition.

-

-

Since both validators satisfy the condition, the restaking graph $G$ is secure according to Claim 1.

-

Introducing the Initial Shock $D = {a}$:

- Consider an initial shock $D = {a}$, meaning validator $a$ loses its entire stake $\sigma_a = \epsilon$.

- Given that $\sigma_a / \sigma_V = \epsilon / (\epsilon + (1 - \epsilon)) = \epsilon \leq \psi$, this shock fits within the shock $\psi$.

- Resulting Graph After the Shock:

- After removing $a$, the remaining graph $G \downarrow D$ consists of the service $x$ supported only by validator $b$.

- Determining the Attack Condition:

- The pair $({x}, {b})$ represents an attack coalition on $G \downarrow D$.

- Since $b$ is the only remaining validator supporting $x$, the attack can succeed if $\sigma_b < \pi_x$. Given that $\sigma_b = 1 - \epsilon$ and $\pi_x = 1$, this condition is satisfied.

- Calculating the Worst-Case Stake Loss:

- The total stake after the shock $D = {a}$ is $\sigma_b = 1 - \epsilon$.

- Since $b$ is insufficient to fully protect $x$, the attack succeeds, leading to a total stake loss of $R_\psi(G) \geq \frac{\sigma_a + \sigma_b}{\sigma_V} = \frac{1}{1} = 1$.

Key Insights from Theorem 2

- Thus, the proof demonstrates that even though the graph $G$ satisfies the EigenLayer condition, it is still vulnerable to a total loss when the initial shock $\psi$ is large enough.

- Specifically, for any $\psi \geq \epsilon$, the entire network’s stake can be wiped out, validating the theorem’s statement that $R_\psi(G) = 1$ for $\psi \geq \epsilon$.

Theorem 3

Statement:

For any $\psi$, $\gamma$, $\epsilon > 0$ such that

there exists a restaking graph $G$ that satisfies the condition $(17)$ from Corollary 2 but has $R_{\psi}(G) \geq \left( 1 + \frac{1}{\gamma} \right) \psi - \epsilon$.

Explanation:

Theorem 3 says that even if a restaking graph $G$ satisfies the security condition from Corollary 2, it can still experience substantial losses. Specifically, the theorem asserts that there can exist a graph where the worst-case loss $R_\psi(G)$ is at least $\left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right)\psi - \epsilon$, indicating that the security condition from Corollary 2 is not sufficient to fully protect against significant losses in the presence of a shock $\psi$.

Understanding the Components

- Graph Components:

- The graph $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$ is constructed with:

- Service: $S$ = { $x$ } (one service $x$).

- Validators: $V$ = { $a, b, c$ } (three validators: $a$, $b$, and $c$).

- Edges: Each validator is connected to the single service $x$ through the edges $E$ = { $(x, a), (x, b), (x, c)$ }.

- The graph $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$ is constructed with:

- Stakes and Parameters:

- Stakes:

- $\sigma_a > 0$: Assume $\sigma_a$ is any positive constant.

- $\sigma_b = \sigma_a \left( \frac{1}{\gamma} - \frac{\epsilon}{\psi} \right)$: Stake of validator $b$.

- $\sigma_c = \sigma_a \left( \frac{1 - \psi + \epsilon}{\psi} - \frac{1}{\gamma} \right)$: Stake of validator $c$.

- Service Profit: $\pi_x = \left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right)\psi - \epsilon$ (the profit from attacking service $x$).

- Security Requirement: $\alpha_x = 1$ (the fraction of the total stake needed to compromise service $x$).

- Stakes:

Proof Breakdown

- Validator $b$:

- The stake $\sigma_b \geq 0$ is ensured by the condition $\epsilon \leq \frac{\psi}{\gamma}$, guaranteeing that $b$ has a non-negative stake.

- Validator $c$:

- Similarly, $\sigma_c \geq 0$ is ensured by the inequality $1 \geq \left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right)\psi - \epsilon$, confirming that $c$ has a non-negative stake.

- Total Stake:

-

The total stake in the network before the shock is given by $\sigma_V = \sigma_a + \sigma_b + \sigma_c$.

\[\sigma_V = \sigma_a + \sigma_b + \sigma_c = \sigma_a \left( \left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right) - \frac{\epsilon}{\psi} + \frac{1 - \psi + \epsilon}{\psi} - \frac{1}{\gamma} \right) = \frac{\sigma_a}{\psi}\]

-

- Validator $a$:

-

The condition from Corollary 2 requires that each validator $v$ satisfies:

\[\sum_{s \in N_G(\{v\})} \frac{\sigma_v}{\sigma_{N_G(\{s\})}} \cdot (1 + \gamma)\pi_s \leq \sigma_v\] -

For validator $a$, substituting the values confirms that:

\[\sigma_a = \sigma_a\]Thus, the condition is satisfied.

-

- Validator $b$:

- A similar calculation for validator $b$ shows that the condition from Corollary 2 is also met for $b$.

- Initial Shock $D$ = { $a$ }:

- The shock $D$ = { $a$ } removes validator $a$ and its stake $\sigma_a$ from the network. The remaining validators $b$ and $c$ now support the service $x$.

- Attack Incentive for Validator $b$:

-

After the shock, we need to determine whether validator $b$ is incentivized to attack the service $x$. Validator $b$ would attack if the expected profit from attacking $x$ exceeds its remaining stake:

\[\pi_x - \sigma_b > 0\] -

Substituting the values, the expression becomes:

\[\pi_x - \sigma_b = \left[\left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right)\psi - \epsilon\right] - \left[\frac{\sigma_a}{\gamma} - \frac{\sigma_a \epsilon}{\psi}\right]\]Simplifying further:

\[\pi_x - \sigma_b = \gamma \epsilon \cdot \frac{\sigma_a}{(1 + \gamma)\psi} > 0\] -

Since the expression is positive, validator $b$ is indeed incentivized to attack service $x$.

-

- Calculating the Loss $R_\psi(G)$:

-

After $b$ attacks, the total loss is given by:

\[R_\psi(G) \geq \frac{\sigma_a + \sigma_b}{\sigma_V} = \left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right)\psi - \epsilon\] -

This proves that the network suffers a substantial loss, as the theorem states.

-

Key Insights from Theorem 3

- Theorem 3 demonstrates that it is possible to construct a restaking graph $G$ that meets the security condition from Corollary 2 but still incurs substantial losses when subjected to a significant shock $\psi$. This reveals a critical vulnerability in the condition, showing that it is not sufficient to prevent large-scale failures under certain circumstances. The proof highlights the importance of developing more robust security measures that go beyond the conditions provided by Corollary 2, ensuring the resilience of decentralized networks against catastrophic events.

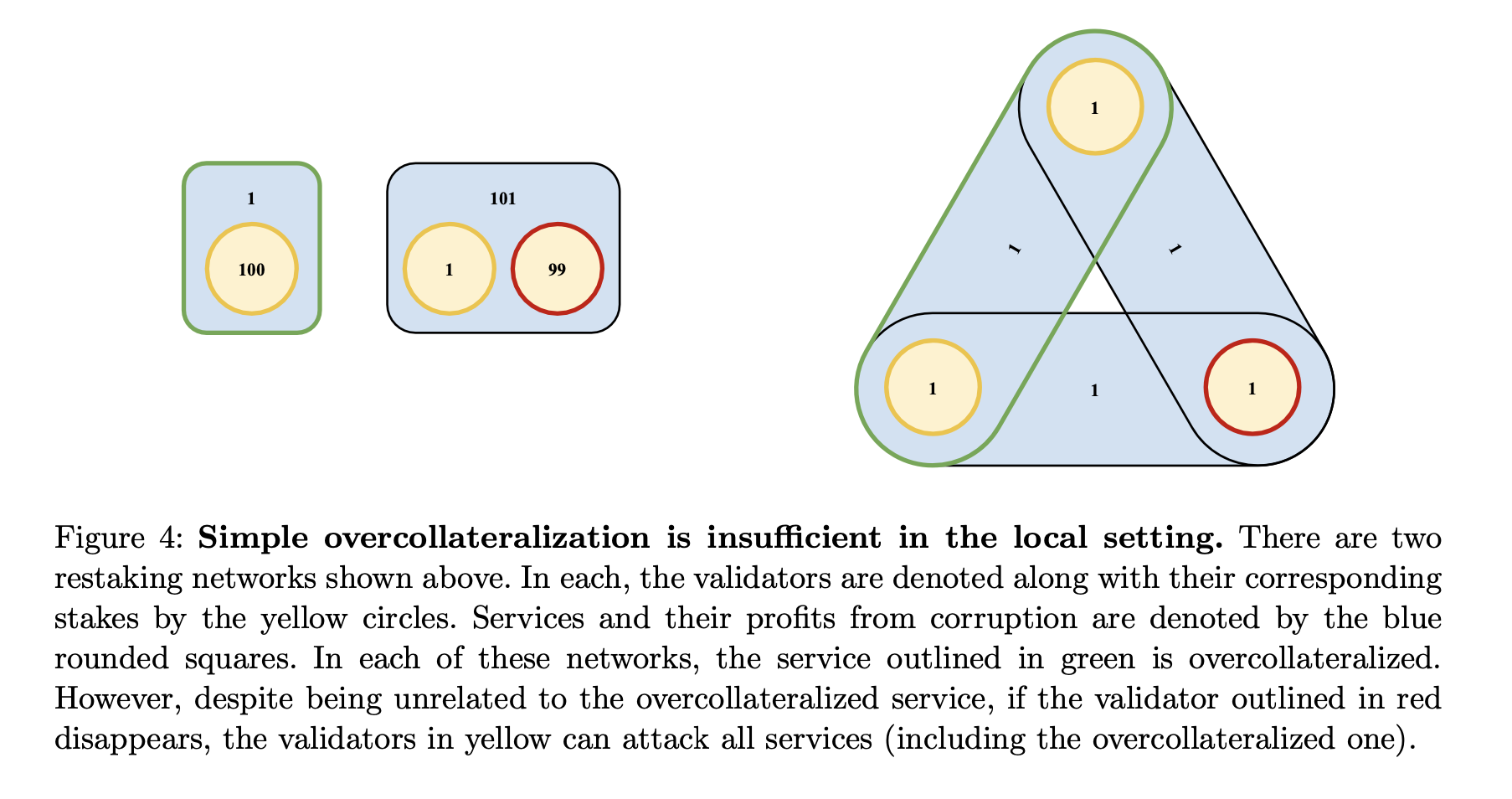

Local Security

Theorem 4

Statement: For any local security condition $f$, any secure restaking graph $G$, and coalition of services $C \subseteq S$ such that $f(C, G) = 1$, there exists a secure $C$-local variant $G’$ of $G$ such that $R_0(C, G’) = 1$.

Explanation: Theorem 4 proves that for any secure configuration of a restaking network, we can always construct a variant of the network where the coalition of services $C$ can experience the worst-case stake loss scenario. This is done by manipulating the overcollateralization and introducing new services and validators to engineer a valid attack on the augmented graph $G’$.

Proof Breakdown

Defining Total Overcollateralization $\Delta$:

- $\Delta = \sigma_{N_G C} - \pi_C$:

- $\sigma_{N_G C}$: The total stake from validators in the neighborhood of coalition $C$, i.e., validators directly securing services in $C$.

- $\pi_C$: The profit that could be made by corrupting the coalition $C$, essentially the value to be gained by attackers.

- $\Delta$ represents the excess collateral securing the coalition $C$, which is important for understanding whether the services in $C$ are overcollateralized (secure).

Augmenting the Graph $G$ to Create $G’$:

-

The proof creates an augmented graph $G’$ by adding a new service $s^*$ and two validators, $a$ and $b$, adjacent only to this new service $s^*$.

- New Validator Stakes:

- $\sigma_a = \Delta + \epsilon$: Validator $a$’s stake is the overcollateralization of $C$ plus a small amount $\epsilon$, ensuring that $a$’s stake is large enough.

- $\sigma_b = \epsilon$: Validator $b$ has a small stake $\epsilon$, used for controlling part of the new attack structure.

- Profit of New Service $s^*$ :

The new service $s^*$ has a profit from corruption $\pi_{s^*} = \Delta + 2\epsilon$, ensuring that its profit potential is directly related to the overcollateralization of $C$.

Validity of the Attack:

-

Validator $a$ is not path-connected to the coalition $C$, meaning that no other validator is dependent on $a$ for the security of services in $C$.

-

This is important because it guarantees that modifying $a$’s stake or security settings will not affect the original security structure of $C$ in graph $G$.

-

By construction, the attack $(C \cup {s^*}, N_G C \cup {b})$ is valid on the new graph $G’$, meaning that the attack could lead to the maximal worst-case loss $R_0(C, G’) = 1$.

-

This proves that for any local security condition $f$, there always exists a modified graph $G’$ where the worst-case scenario for the coalition $C$ results in a maximal stake loss.

Key Insights from Theorem 4

- Even if a coalition of services $C$ is secure, Theorem 4 says that it’s always possible to modify the network slightly—by adding a new service and some validators—such that the worst possible loss for $C$ becomes as bad as it can get. In this modified network, the security becomes local to $C$, and the coalition $C$ can be attacked with maximal loss.

Local Security Condition for Stable Attacks

Theorem 5

Statement: In a restaking graph $G$, let $C \subseteq S$ be a coalition of services. If, for all attack headers $(X, Y)$ where $X \subseteq C$, the inequality $(1 + \gamma) \pi_X \leq \sigma_Y$ holds, then the worst-case loss $R_\psi(C, G)$ for coalition $C$ is strictly less than $\left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma} \right)\psi$. Furthermore, the function that checks whether this inequality holds for all attack headers is a local security condition.

Explanation: Theorem 5 guarantees that a well-collateralized network can limit the potential loss from any attack, and it provides a method to check this condition locally, making it more practical for real-world use in securing blockchain networks.

Proof Breakdown

Condition for Limiting Worst-Case Loss:

-

The condition that needs to be satisfied for the worst-case loss to be limited is:

\[(1 + \gamma)\pi_X \leq \sigma_Y\]This inequality states that the stake of the validators protecting the services in $X$ must be large enough to cover the potential profit from corrupting the services, scaled by a safety margin $\gamma$. This ensures that attackers cannot easily exploit the coalition of services $C$ because the validators have sufficient collateral to protect against attacks.

Sequence of Attacks and Validator Loss:

-

The proof considers an arbitrary sequence of cascading attacks on the coalition $C$, represented by $(A_1, B_1), \dots, (A_T, B_T)$, where each attack involves a subset of services $A_t$ being attacked and validators $B_t$ potentially losing their stake.

-

For each attack step $t$, a set $L_t$ is defined, representing the validators who were lost in that specific attack. These are the validators who were exclusively securing the services in $C$ and were compromised during the attack.

Maximal Set of Services $A_t’$:

-

The proof introduces the set $A_t’$, which is defined as the maximal subset of services that can still be considered part of an attack coalition in each step. These services are secured by a combination of validators from $B_t$ and other validators remaining in the system.

-

The services in $A_t’$ satisfy the condition:

\[\sigma_{B_t \setminus L_t} \geq \alpha_s \cdot \sigma_{N_G\{s\} \setminus \left( \bigcup_{i=1}^{t-1} B_i \cup D \right)}\]meaning that the remaining validators $B_t \setminus L_t$ provide enough stake to meet the attack resistance required for the services in $A_t’$.

-

The proof concludes by showing that under the condition $(1 + \gamma) \pi_X \leq \sigma_Y$, the worst-case loss $R_\psi(C, G)$ remains strictly less than $\left( 1 + \frac{1}{\gamma} \right)\psi$. In other words, the maximum possible stake loss for the coalition $C$ is effectively bounded and controlled.

-

Additionally, the function that checks whether the condition holds for all attack headers is a local security condition. This means that it can be verified by examining only the services and validators in the immediate neighborhood of $C$, without needing to consider the entire network.

Key Insights from Theorem 5

Theorem 5 provides a framework for bounding the worst-case loss in a restaking network by ensuring that validators have enough stake to cover any potential attack on a coalition of services. Specifically, it shows that:

-

If validators’ stake is greater than the attack profit for all possible attack scenarios, the worst-case loss for the coalition will not exceed a specific upper bound. This ensures that the network remains resilient to attacks.

-

The process of checking whether this condition holds is local, meaning it can be done efficiently by focusing on the relevant subset of services and validators, rather than analyzing the entire network.

Lower Bounds for Local Security

Theorem 6

Statement:

For any $\gamma > 0$, there exists a restaking graph $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$ that satisfies condition (17) from Corollary 2, but there also exists a coalition $C \subseteq S$ such that the worst-case loss $R_0(C, G) = 1$.

Explanation:

This means that even though the graph satisfies the security condition for some services, it is still possible for a subset of services to experience the maximal possible loss in a worst-case attack scenario.

Proof Breakdown

Defining the Restaking Graph:

-

Services and Validators:

\[E = \{(x, a), (x, b), (y, b), (y, c), (z, c), (z, a)\}\]

Let the services be $S = {x, y, z}$, and the validators be $V = {a, b, c}$. The edges $E$ define which validators secure which services, and they are given by:This creates a circular pattern where each validator is responsible for securing two services.

-

Setting Stake and Profit Parameters:

- Set the profit for each service as $\pi_x = \pi_y = \pi_z = \pi$, where $\pi > 0$ is an arbitrary positive constant.

-

Set the stake of validator $a$ to $\sigma_a$, and choose $\sigma_a$ such that:

\[\sigma_a < 2\pi\] -

Set the stakes of validators $b$ and $c$ as:

\[\sigma_b = 2(1 + \gamma)\pi, \quad \sigma_c = 2(1 + \gamma)\pi\]

Checking Security Condition (17) from Corollary 2:

-

The security condition (17) from Corollary 2 must be satisfied, which ensures that the validators’ stakes are sufficient to secure the services. We need to verify this for the given stake values.

-

For validator $a$:

\[\frac{\sigma_a}{\sigma_a + \sigma_b} \cdot (1 + \gamma)\pi + \frac{\sigma_a}{\sigma_a + \sigma_c} \cdot (1 + \gamma)\pi < (1 + \gamma)\pi\]Simplifying this expression ensures that validator $a$’s stake satisfies the security condition.

-

For validators $b$ and $c$, similar inequalities are checked:

\[\frac{\sigma_b}{\sigma_a + \sigma_b} \cdot (1 + \gamma)\pi + \frac{\sigma_b}{\sigma_b + \sigma_c} \cdot (1 + \gamma)\pi < \sigma_b\] \[\frac{\sigma_c}{\sigma_a + \sigma_c} \cdot (1 + \gamma)\pi + \frac{\sigma_c}{\sigma_b + \sigma_c} \cdot (1 + \gamma)\pi < \sigma_c\]These inequalities confirm that the graph satisfies condition (17), meaning that the validators’ stakes are sufficient to protect the services under normal conditions.

Defining the Coalition $C$:

-

Let $C = {x, z}$ be the coalition of services that will be targeted in a potential attack.

-

Consider a shock $D = {b, c}$, where validators $b$ and $c$ experience a failure or attack. Since their stakes are large, their failure could cause cascading losses.

Establishing the Maximal Loss:

-

Since $\sigma_a < 2\pi$ and $\pi_x + \pi_z = 2\pi$, the stake of validator $a$ is not enough to cover the total profit from corrupting the services $x$ and $z$.

-

As a result, the set ${x, z}$ and the validator ${a}$ form a stable attack coalition, leading to the maximal loss for the coalition of services $C = {x, z}$.

-

The shock $D = {b, c}$ removes validators $b$ and $c$, leaving only $a$ to secure $C$. Since $a$’s stake is insufficient, the services in $C$ are compromised, and $R_0(C, G) = 1$.

Key Insights from Theorem 6

Theorem 6 demonstrates that even if a restaking graph satisfies the security condition from Corollary 2, there can still exist a coalition of services that experiences the worst-case loss in a particular attack scenario. Specifically, this shows that:

-

Security conditions can be satisfied globally, but there may still be local vulnerabilities that allow a subset of services to experience catastrophic losses.

-

By carefully constructing the stake distribution and service-validator connections, it is possible to create scenarios where a specific subset of services $C$ becomes vulnerable to attacks, despite the overall network appearing secure.

Long Cascades

Theorem 7

Statement: Suppose that a restaking graph $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$ is secure with $\gamma$-slack for some $\gamma > 0$. Let $\sigma_V$ denote the minimum stake held by any validator. For any $\psi > 0$, let $B_0 \in D_\psi(C, G)$ represent the initial disturbance or set of compromised validators. Then for the reference depth $k$, the number of attack rounds $T$ must satisfy:

\[T < k \left( 1 + \log_{1 + \gamma} \frac{\psi \cdot \sigma_V}{\epsilon \gamma} \right)\]where $\epsilon$ represents the threshold for cascading failures within the network.

Explanation: Theorem 7 guarantees that while an attack can spread through a restaking network, it cannot propagate forever. The system is designed to limit the number of rounds an attack can last, ensuring that the network eventually stabilizes and avoids total collapse.

Proof Breakdown

Reference Depth and Attack Cascade:

-

The theorem analyzes how an attack propagates through the network by focusing on the reference depth $k$, which measures how deeply the attack can penetrate the system. The cascading impact is broken down into multiple stages or attack rounds.

-

For each attack sequence $(A_1, B_1), \dots, (A_T, B_T)$, the attack propagates from the initial disturbance $B_0$ and compromises additional validators in each round.

-

The attack must satisfy certain constraints based on the validator stake, the slack factor $\gamma$, and the number of stages the attack can progress.

Attack Propagation and Validator Loss:

-

At each stage $i$, the validators securing the services in the attack sequence $A_i$ are lost, leading to a cascading failure. The sets $A_i’$ and $B_i’$ represent the maximum set of services and validators compromised in each round, respectively.

-

By applying the conditions in Corollary 1, we can validate that each stage of the attack sequence is a valid attack on the restaking graph $G$, and the number of validators lost in each round is calculated.

-

The attack propagates by moving through validators and services in the system, but there are constraints on how many rounds of attacks can occur based on the available stake and security conditions.

Validity of Attack at Each Stage:

- The proof ensures that the sequence of attacks remains valid by applying Corollary 1 multiple times. At each stage, the condition must hold, meaning the stake of the compromised validators exceeds the cumulative stake required to secure the remaining validators in future stages.

- This ensures that each stage of the attack has a sufficient impact to continue propagating, but the number of attack rounds is constrained by the slack factor $\gamma$.

Inductive Argument and Upper Bound on Attack Rounds:

-

The proof concludes by using an inductive argument to show that the sequence of attacks leads to a decreasing stake for the compromised validators at each stage. The sequence $X_i$ is defined to measure the remaining stake at each step, starting with an initial stake $X_0$.

-

The total number of attack rounds $T$ is bounded by the reference depth $k$ and the logarithmic factor involving the minimum validator stake $\sigma_V$, the disturbance size $\psi$, and the slack factor $\gamma$.

Final Bound on Attack Rounds $T$:

-

The final result shows that the number of attack rounds $T$ must satisfy the inequality:

\[T < k \left( 1 + \log_{1 + \gamma} \frac{\psi \cdot \sigma_V}{\epsilon \gamma} \right)\]This means that the attack cannot continue indefinitely, and the number of rounds is constrained by the security conditions of the network. The slack factor $\gamma$ and the minimum validator stake $\sigma_V$ both play a key role in limiting the attack’s propagation.

Key Insights from Theorem 7

Theorem 7 provides an upper bound on the number of attack rounds that can occur in a restaking network. It demonstrates that:

- Attacks are limited by validator stake and slack

- The propagation of attacks through the network is constrained by the smallest validator stake and the security buffer provided by the $\gamma$-slack.

- Cascading failures are bounded

- While an attack may spread through the network, the number of stages or rounds the attack can propagate is limited. This ensures that the system can recover after a finite number of rounds, rather than experiencing an unbounded collapse.

- Security condition controls the depth of the attack

- The depth of the attack (how far it spreads) is controlled by the reference depth $k$ and the logarithmic factor involving the validator stake and slack. Networks with larger slack or better-collateralized validators can withstand deeper attacks without catastrophic failure.

Lower Bounds under a Bounded Profit-Stake Ratio

Theorem 8

Statement: For any $0 < \epsilon < 1$, there exists a secure restaking graph $G = (S, V, E, \pi, \sigma, \alpha)$ that meets the EigenLayer condition (denoted by Equation (3)), with the ratio $\max_{(s, v) \in S \times V} \frac{\pi_s}{\sigma_v} = 2$. However, there exist proper subsets $C \subset S$ such that the worst-case loss $R_0(C, G) = 1$, meaning maximal loss for the subset $C$. Furthermore, for any $\psi \geq \epsilon$, the cascading loss $R_\psi(S, G) = 1$, meaning that the entire graph can experience cascading failures for sufficiently large disturbances.

Explanation: Theorem 8 shows that while a network might appear secure overall, there can still be pockets of vulnerability where certain subsets of services are at risk of total failure. Moreover, large disturbances can cause these vulnerabilities to spread, leading to widespread losses across the entire network.

Proof Breakdown

Setting up the graph structure:

-

Choice of Validators $V$ and Services $S$:

Let $n$ represent the number of validators, and choose $n$ such that $n$ is divisible by 6 (i.e., $6 \mid n$). The set of validators $V$ consists of $n$ validators, each with a stake $\sigma_v = 1$.Next, define the set of services $S$ to consist of $3N$ services, where $N = \frac{n}{6}$. Each service $s \in S$ has a profit from corruption $\pi_s = 2$ and a parameter $\alpha_s = 1$.

Partitioning the services:

- Split the services $S$ into two disjoint sets:

- $S_6$ contains $N$ services, where each service in $S_6$ secures 6 validators.

- $S_3$ contains the remaining $2N$ services, where each service in $S_3$ secures 3 validators.

Defining the edges in the graph:

- The edges $E$ are defined to create a single connected component:

- For services in $S_6$, the edges are drawn such that the neighborhood $N_G{s}$ partitions the set of validators $V$ into groups of 6.

- For services in $S_3$, the edges are drawn so that $N_G{s}$ partitions the validators into groups of 3.

- This configuration ensures that each validator $v \in V$ is adjacent to one service from $S_6$ and one service from $S_3$.

Satisfying the EigenLayer condition (3):

-

To check whether the EigenLayer condition is satisfied, we evaluate the security equation for any validator $v \in V$:

\[\sum_{s \in N_G\{v\}} \frac{\sigma_v}{\sigma_{N_G\{s\}}} \cdot \frac{\pi_s}{\alpha_s} = \frac{1}{6} \cdot 2 + \frac{1}{3} \cdot 2 = \sigma_v\]Since each validator is connected to one service in $S_6$ and one in $S_3$, the sum on the left-hand side equals the validator’s stake $\sigma_v = 1$. This confirms that the graph satisfies the EigenLayer condition.

Demonstrating maximal loss for subsets $C$:

-

The theorem constructs subsets $C \subset S$ where the worst-case loss occurs. Specifically, it identifies proper subsets of services $C$ where the entire subset is compromised, leading to the maximal loss $R_0(C, G) = 1$.

-

The configuration of services and validators ensures that if a disturbance $\psi$ affects the right set of services, it can result in the full loss of stake for validators securing those services.

Cascading failures for $\psi \geq \epsilon$:

-

When the disturbance $\psi$ exceeds the threshold $\epsilon$, the network experiences cascading failures. The initial attack on a subset of services triggers a chain reaction that causes the entire graph $G$ to collapse, leading to $R_\psi(S, G) = 1$.

-

This shows that while the graph satisfies the EigenLayer condition, it is still vulnerable to large disturbances that can propagate through the network.

Key Insights from Theorem 8

Theorem 8 provides an important insight into the vulnerability of restaking networks, even when they satisfy important security conditions like the EigenLayer condition. Specifically, it demonstrates that:

- Global security doesn’t prevent local failures

- Even though the network as a whole satisfies the EigenLayer condition, it is possible to identify subsets of services that can experience maximal losses in a worst-case attack. This highlights that global security guarantees do not always protect against localized failures.

- Cascading failures

- For large enough disturbances $\psi$, the network can experience cascading failures, where an initial attack spreads through the network, causing validators to lose all their stake. This shows that systemic risk can still exist, even in networks that are designed to be secure under normal conditions.

- Real-world relevance

- In real-world restaking networks (such as those involving cross-staked validators securing multiple services), Theorem 8 highlights the need to carefully analyze local vulnerabilities and the potential for cascading failures, even when the system meets broader security criteria.

References

-

EigenLayer Team. Eigenlayer: The restaking collective. URL: https://docs.eigenlayer.xyz/overview/whitepaper, 2023 ↩