Note: This article is inspired by Barnabé’s article More pictures about proposers and builders. I am very inspired by his writings on Ethereum. Hence this article is dedicated to him.

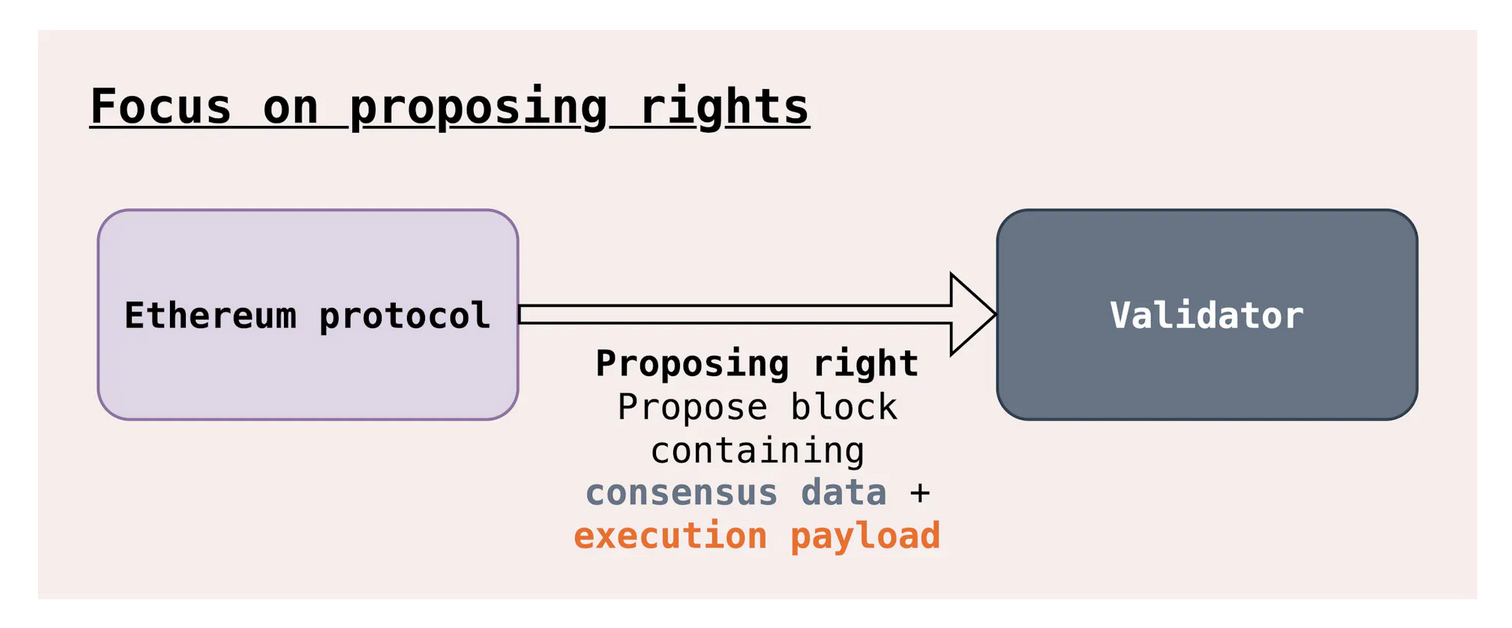

Proposing Rights and the Role of Validators

Figure: Proposing Rights and the Role of Validators, Credit by Barnabé Monnot

Imagine you’re at a huge music festival, and there’s one microphone that anyone can use—but first, you need a ticket to access it. In the Ethereum world, this “microphone” is the ability to propose a block of transactions. Validators are like ticket holders who get a turn to announce (propose) which songs (transactions) will play next.

Initially, validators have two main rights:

- The right to propose the consensus data block (“beacon block”): This is like deciding the theme of the music for the next few moments.

- The right to propose the execution payload: This involves choosing the specific songs to play.

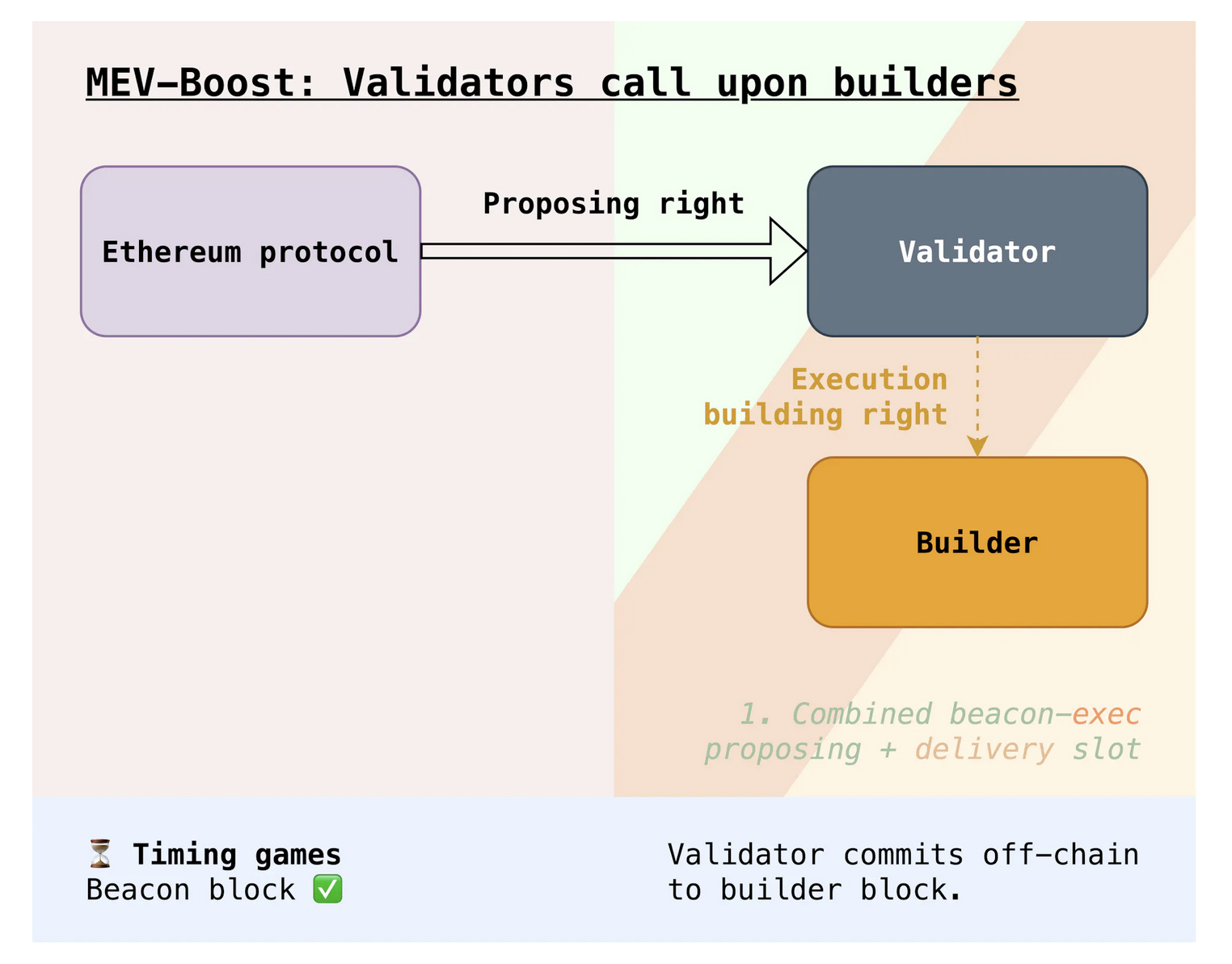

Introduction of MEV-Boost and Building Rights

Figure: MEV-Boost and Building Rights, Credit by Barnabé Monnot

Soon, validators realize that choosing the next songs can be quite valuable—maybe some songs or advertisements are willing to pay to be played next. So, they start a system where they can sell this choice to others (builders) who will pay them for the chance to line up the next tracks. This is done through something called MEV-Boost.

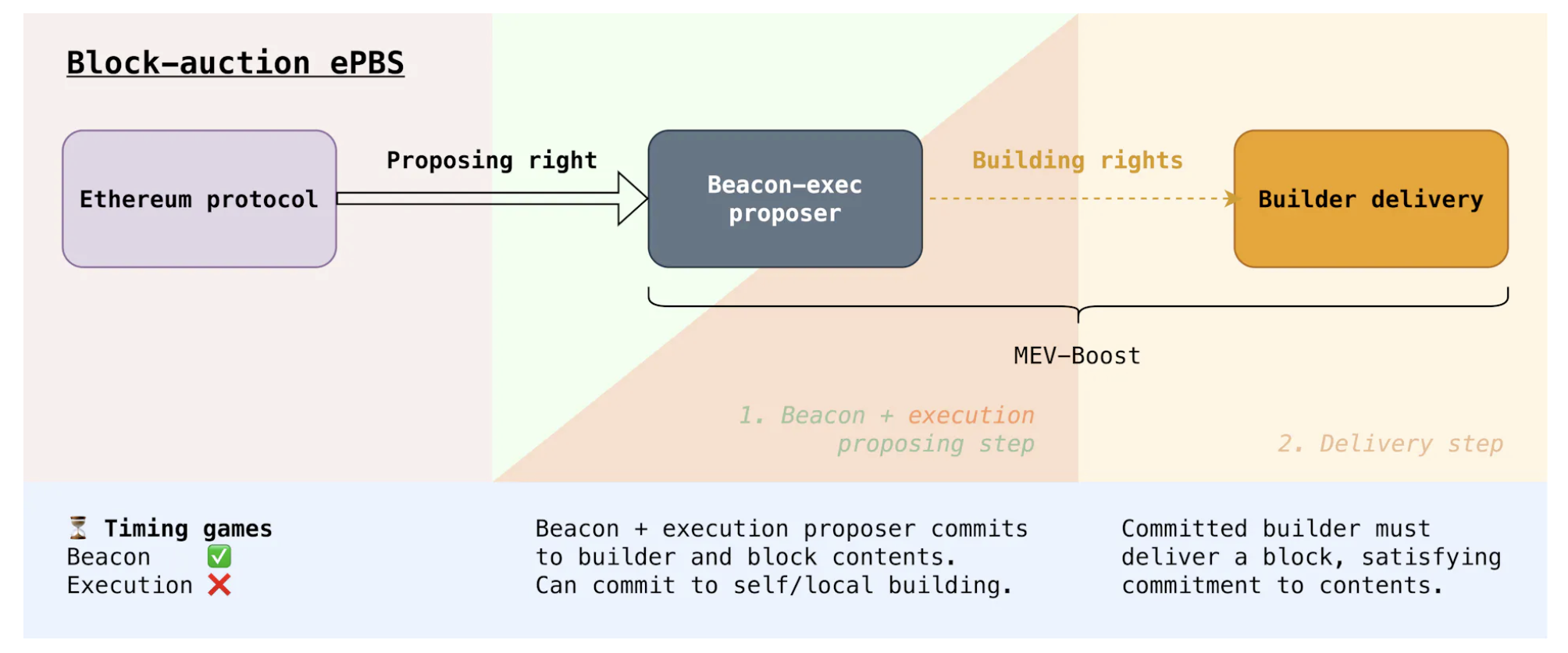

Block-auction ePBS: Trying to Regain Control

Figure: Block-auction ePBS, Credit by Barnabé Monnot

The festival organizers notice that letting people pay for song choices outside their official system might cause issues (like unfair song choices or security risks). So, they develop a new method called “enshrined Proposer-Builder Separation” (ePBS), where validators can still strike deals with builders, but without needing a middleman. This aims to:

- Ensure the honest validator gets paid whether or not the builder delivers.

- Reduce the need to trust others not to mess up.

- Keep the song choosing (consensus data) separate from song playing (execution payload).

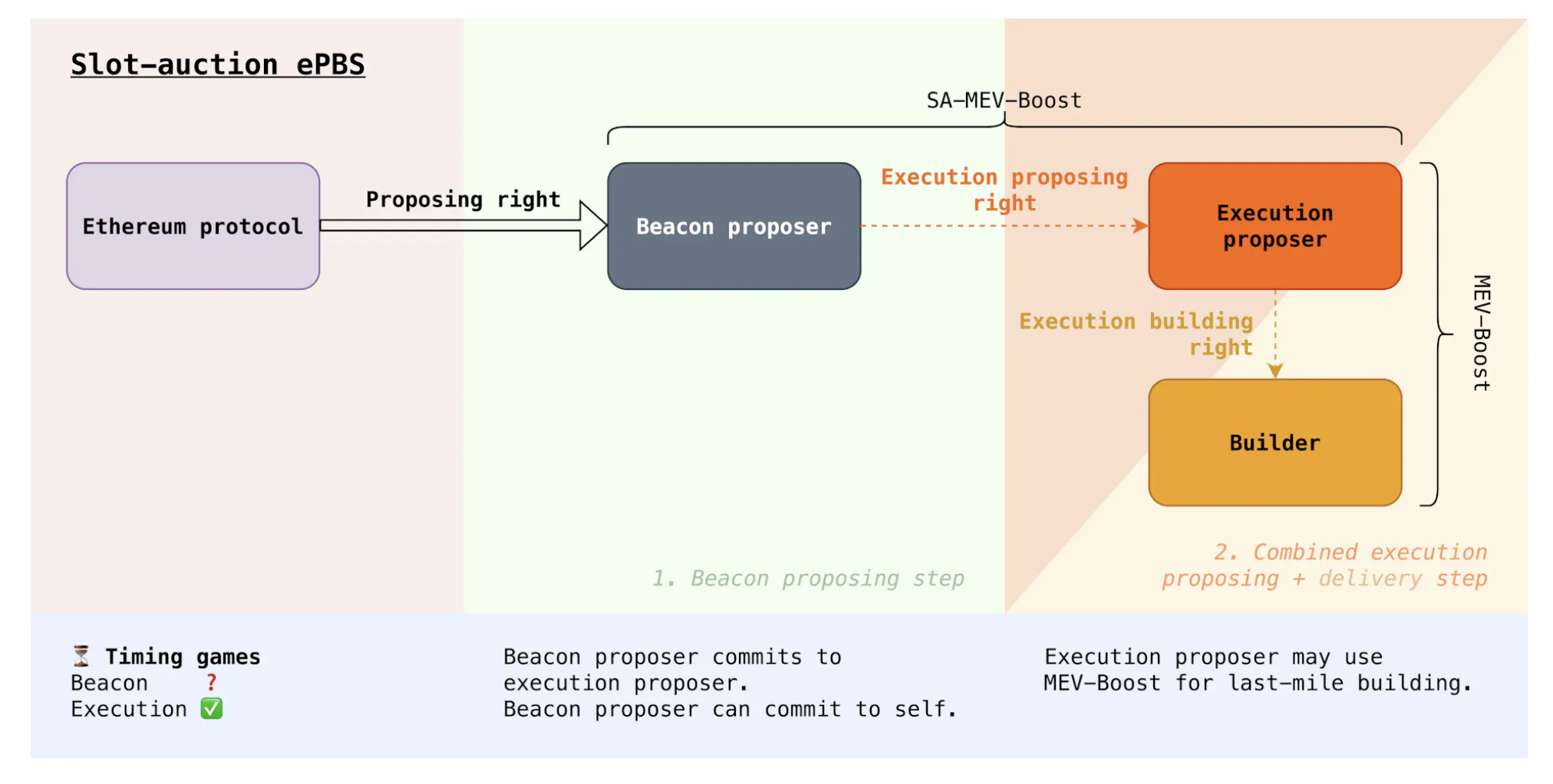

Slot-auction ePBS: Simplifying the Process

Figure: Slot-auction ePBS, Credit by Barnabé Monnot

Here, instead of committing to specific songs, the validator commits to a specific DJ (execution proposer) who decides the playlist. This minimizes timing games—where validators might wait till the last minute to propose, hoping for a better deal.

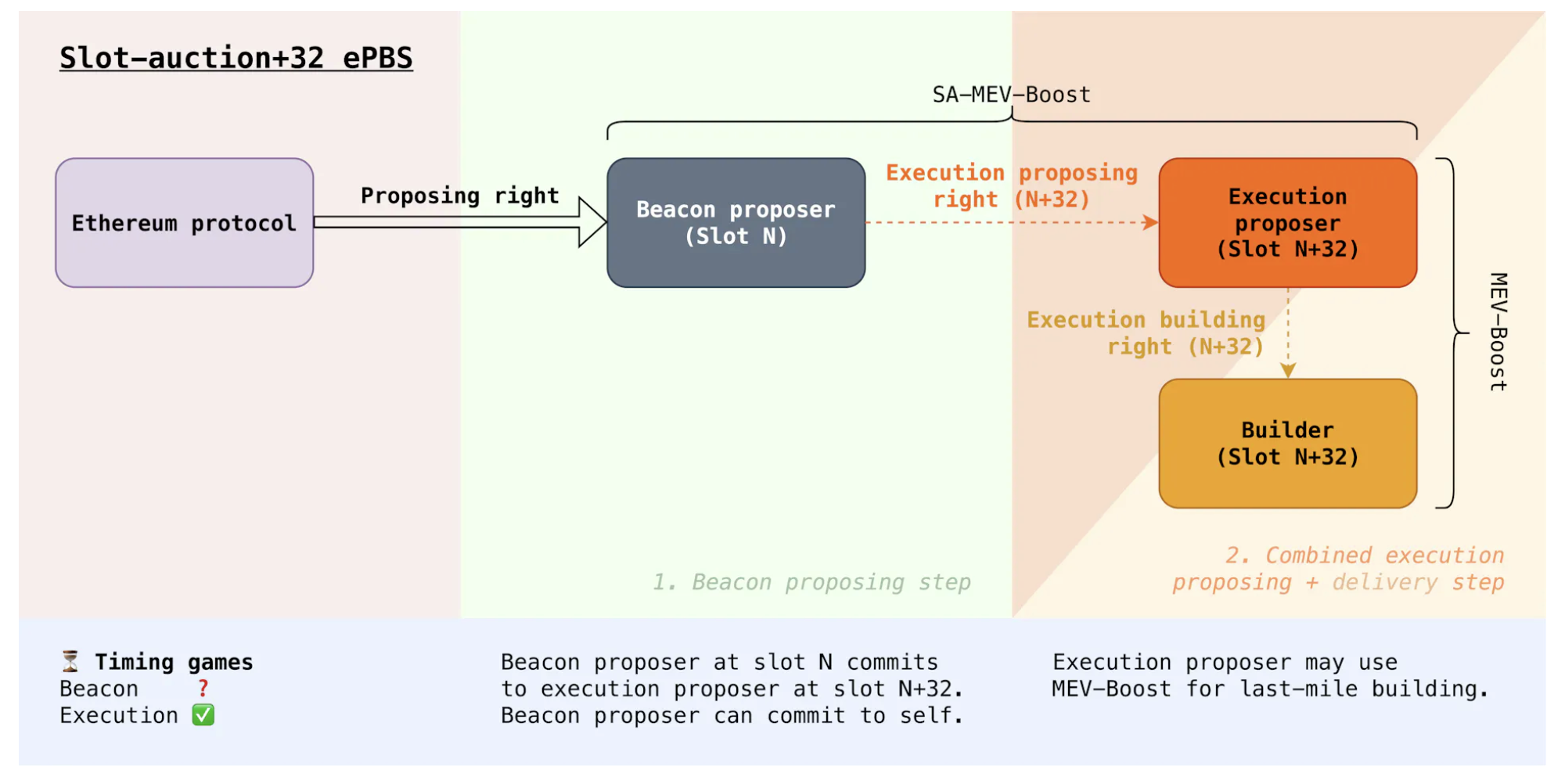

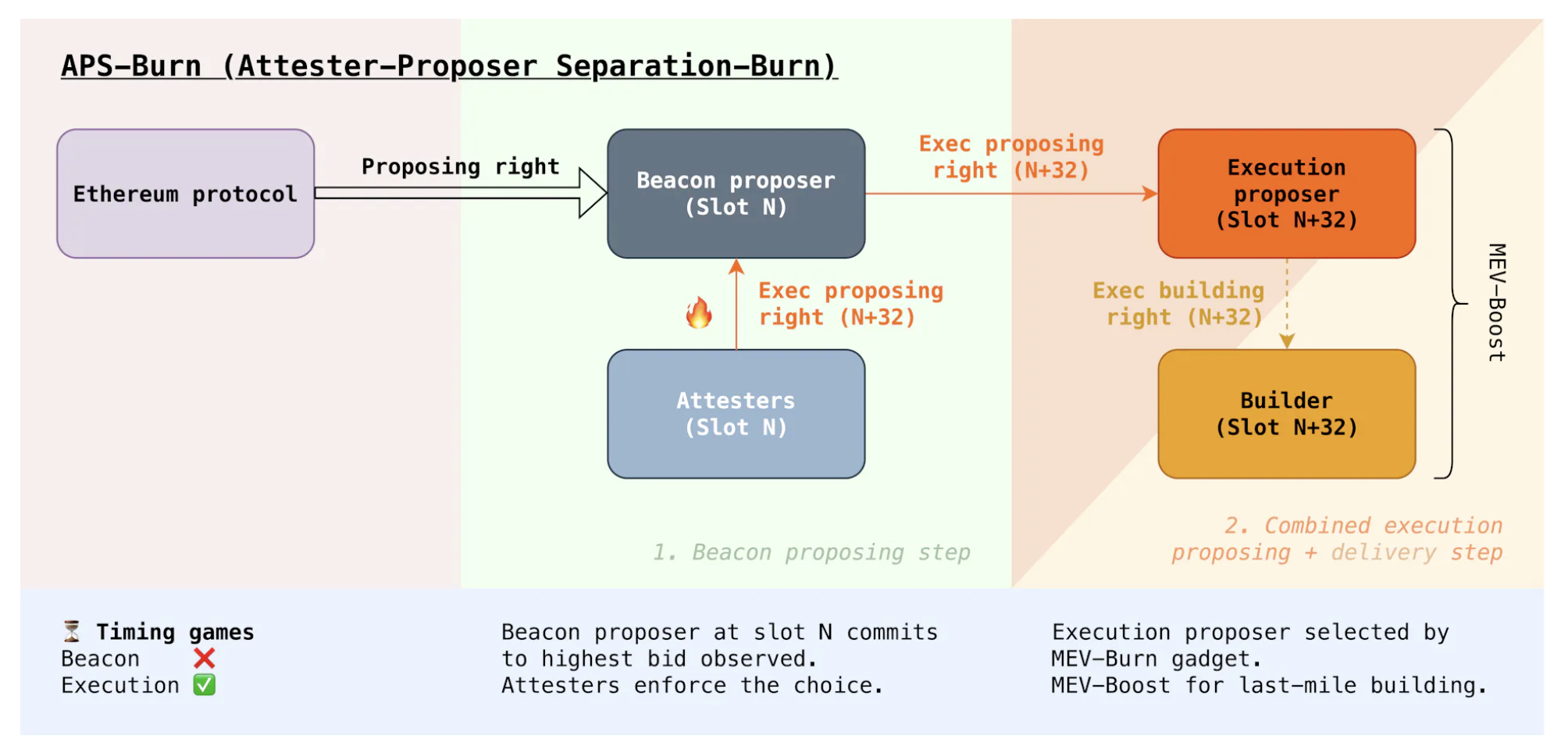

Slot-auction+32 ePBS and APS-Burn: Looking Towards the Future

Figure: Slot-auction+32 ePBS, Credit by Barnabé Monnot

These new methods try to address some deeper issues:

- Slot-auction+32 ePBS: This is like deciding who will be the DJ not just for the next set but for one that starts 32 sets later, which helps reduce immediate biases or manipulations.

Figure: ASP-Burn, Credit by Barnabé Monnot

- APS-Burn: Validators now focus on choosing bids for future slots based more on average expectations rather than immediate gains.

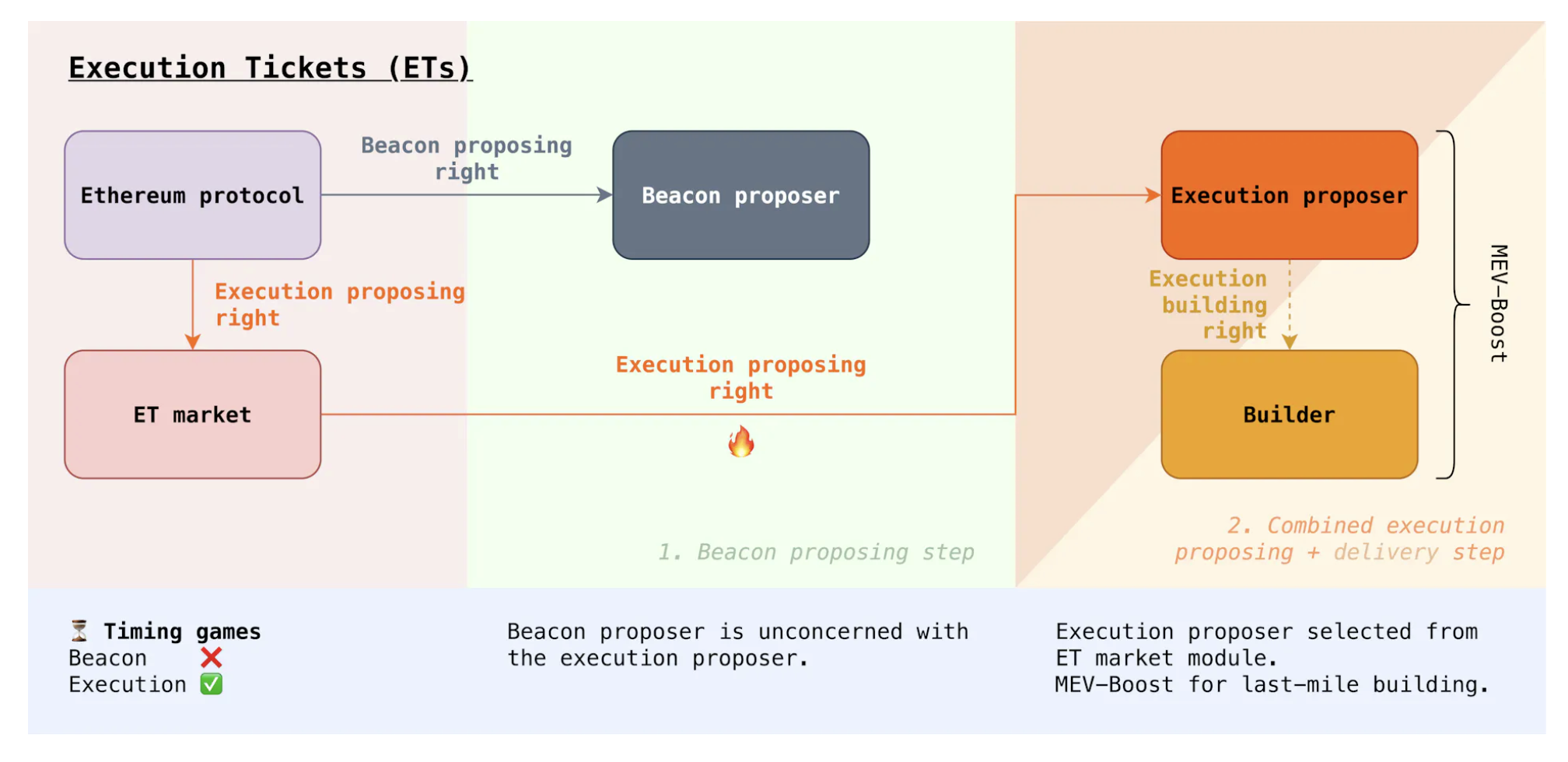

Execution Tickets (ETs)

Figure: Execution Tickets, Credit by Barnabé Monnot

This is like having a raffle ticket that lets you be a DJ at some random future time. It’s less predictable, which could make it fairer but also more uncertain for ticket holders.

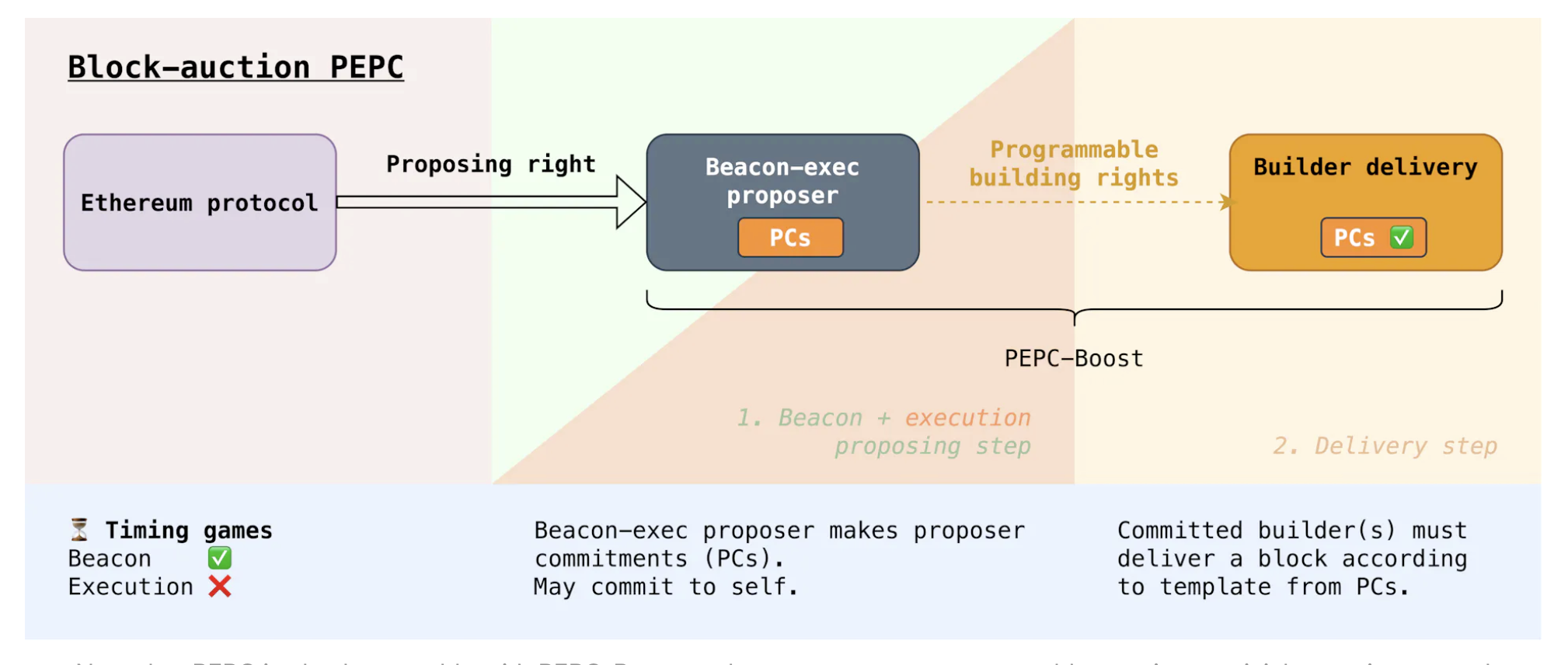

Protocol-Enforced Proposer Commitments - PEPC

Figure: Block-auction PEPC, Credit by Barnabé Monnot

PEPC, like our DJ-controlled stage at a music festival, introduces a structured yet flexible approach to performance that ensures certain highlights are guaranteed, while still allowing room for innovation and participation from various players. It’s a blend of strict planning and creative expression, crucial for maintaining both the excitement and the integrity of the festival.

Setting the Stage: The Role of the DJ (Execution Proposer)

Imagine that at a massive music festival, there’s a special stage where the DJ (the execution proposer) not only plays music but also sets specific rules about the playlist. This DJ has the unique power to enforce these rules, making sure that certain fan-favorite songs (specific transactions) must be played at certain times during the set.

PEPC: The Playlist Commitments

- Proposing the Playlist: The DJ, let’s call her DJ Alice, has a set list that is not just a suggestion but a binding contract. She commits to including certain tracks (specific transactions) at specific times in her set. This commitment is like a published setlist that festival-goers (block validators) can see beforehand; it’s non-negotiable and part of the festival’s official lineup.

- Selling the Right to Play (Building Rights): DJ Alice decides she wants to crowdsource part of her set. She offers other DJs (builders) the chance to play a segment of her time on stage but under strict conditions—they must play the exact songs she has specified. DJ Bob sees an opportunity and agrees to pay DJ Alice for the privilege of playing this segment, under her conditions.

- Enforcing the Playlist: As DJ Bob takes the stage, he must adhere to the playlist commitments that DJ Alice has set. The crowd (validators of the blockchain) knows what to expect and will only approve (validate) Bob’s performance if he sticks to the agreed-upon setlist. If Bob deviates, his segment is cut off (the block is rejected), but DJ Alice still gets paid because Bob agreed to her terms publicly.

How PEPC Fits Into the Larger Festival

PEPC ensures that even if different DJs are playing, the integrity of the music festival is maintained by adhering to a pre-approved, fan-favorite playlist. This system:

- Enhances Security and Predictability: Just as festival-goers appreciate knowing what songs to expect, blockchain users value knowing that certain transactions will definitely be processed.

- Facilitates Collaboration While Maintaining Standards: By allowing other DJs to contribute to the set under strict guidelines, DJ Alice promotes diversity in music while ensuring quality control.

Future Enhancements: Real-Time Playlist Adjustments

Looking ahead, imagine a system where DJ Alice can make last-minute changes to the playlist based on real-time feedback from the crowd or emerging music trends. Such flexibility would represent a more dynamic and responsive blockchain system, where execution proposers can adjust their commitments just before they go live, optimizing both performance and audience satisfaction.